Scientists Discover an Unexpected Wintertime Spike in Oceanic Iron Levels Near Hawaii

Phytoplankton may be tiny, but they play a massive role in how our planet works. Floating near the ocean’s surface, these microscopic organisms help regulate Earth’s climate by absorbing carbon dioxide and driving marine food webs. To survive and grow, phytoplankton rely on a steady supply of nutrients — and one of the most important, yet least understood, is dissolved iron.

A new scientific study has now uncovered something surprising happening in the waters near Hawaii: a previously undetected wintertime spike in dissolved iron that could reshape how scientists understand nutrient cycling in the open ocean. The findings offer new insights into how iron moves through marine ecosystems and why even small changes can have big consequences for ocean productivity and climate processes.

Why Iron Matters So Much in the Ocean

Iron is considered a micronutrient, meaning phytoplankton need only tiny amounts of it. However, those small quantities are absolutely critical. Without enough iron, phytoplankton growth slows or stops, reducing their ability to absorb carbon dioxide and support marine life higher up the food chain.

In many parts of the ocean — especially nutrient-poor regions like the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre — iron availability can be the single factor that limits biological activity. Because of this, understanding where iron comes from, how it moves, and how long it stays in surface waters is a major focus of oceanographic research.

The Study and Where It Took Place

The new research was carried out by Eleanor S. Bates and Nicholas J. Hawco and published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. The scientists focused their work on Station ALOHA (A Long-Term Oligotrophic Habitat Assessment), a well-known marine research site located about 100 kilometers north of Oahu, Hawaii.

Between 2020 and 2023, the research team collected seawater samples during 21 separate research cruises. These samples were taken from the upper layers of the ocean, where phytoplankton live and where iron availability is most critical. Back in the lab, the scientists carefully measured dissolved iron concentrations, along with other trace elements such as titanium and aluminum, to better understand iron sources and seasonal changes.

Confirming a Known Springtime Pattern

The analysis first confirmed something scientists already suspected. Every spring, dissolved iron levels near Station ALOHA tend to rise. This increase is caused by dust storms in Asia, which send iron-rich particles high into the atmosphere. Winds then carry that dust thousands of kilometers across the Pacific Ocean, where it eventually settles into the water near Hawaii.

This springtime dust-driven iron input has been well documented for years and is known to stimulate phytoplankton growth during certain times of the year. But while this pattern was expected, the researchers noticed something else hiding in the data.

The Surprising Wintertime Iron Spike

What truly stood out was a clear spike in dissolved iron during the winter months. This winter increase had not been detected in earlier studies and could not be explained by Asian dust deposition, which is much weaker during that season.

To uncover the source of this iron, the researchers examined chemical fingerprints in the seawater. In particular, they looked at the ratios of dissolved titanium to aluminum, elements that are often used to trace material originating from land.

These chemical clues pointed to a local source rather than a distant one. The evidence strongly suggested that the iron was coming from the Hawaiian Islands themselves.

How Hawaii May Be Feeding the Ocean

During winter, Hawaii experiences increased rainfall and stronger ocean swells. Heavier rains can wash sediment off the islands and into surrounding coastal waters. At the same time, winter swells and ocean circulation can transport this sediment farther offshore, eventually reaching Station ALOHA.

This sediment contains iron-rich minerals that can dissolve into seawater, creating the observed wintertime iron spike. In other words, Hawaii may be acting as a seasonal supplier of iron to the surrounding open ocean — a process that had been largely overlooked until now.

A Steady but Fast Iron Cycle

Another major finding from the study involves how quickly iron moves through the upper ocean. Despite clear seasonal ups and downs in iron concentration, the researchers estimated that each molecule of dissolved iron remains in the upper ocean for about five months before being removed or replaced.

This result is important because previous estimates of iron residence time ranged wildly — from just a few days to several decades. A five-month turnover suggests a system that is dynamic but relatively stable, with iron constantly being supplied, used by organisms, and recycled.

Why This Discovery Matters

The discovery of a wintertime iron source has important implications for understanding phytoplankton ecology, especially in nutrient-poor regions like the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Phytoplankton in these waters often operate on a narrow nutrient margin, meaning even small changes in iron availability can significantly affect growth rates, nitrogen fixation, and carbon uptake.

Since phytoplankton help regulate atmospheric carbon dioxide, changes in iron supply can also influence global climate processes. Climate and biogeochemical models may now need to account for local island-derived iron inputs, not just long-range dust transport, when predicting ocean productivity.

Extra Context: Where Else Does Oceanic Iron Come From?

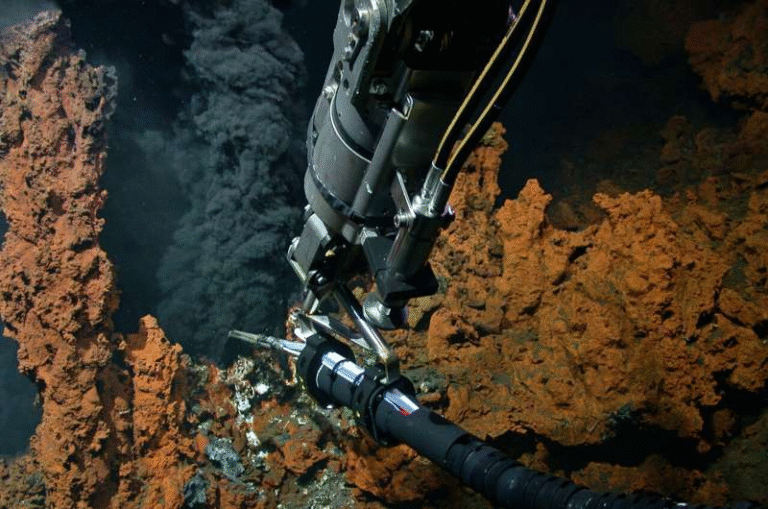

Iron enters the ocean through several pathways. The most well-known sources include atmospheric dust, river runoff, and hydrothermal vents on the seafloor. In coastal regions, sediment resuspension and erosion can also release iron into the water.

What makes the Hawaii finding especially interesting is that it highlights how islands themselves can influence open-ocean chemistry, even far from shore. This challenges the idea that remote ocean regions are only shaped by distant sources and emphasizes the importance of regional geography.

Extra Context: Phytoplankton and Climate Regulation

Phytoplankton are responsible for roughly half of the world’s photosynthesis, rivaling all land plants combined. Through the biological carbon pump, they absorb carbon dioxide and transfer some of it to deeper ocean layers when they die or are consumed.

Iron availability can directly affect how efficiently this process works. When iron is scarce, phytoplankton growth slows, reducing carbon uptake. When iron becomes available — even briefly — it can trigger bursts of biological activity with long-lasting effects.

Looking Ahead

This study opens the door to new questions. How common are island-derived iron inputs elsewhere in the world? Could climate change, by altering rainfall patterns and storm intensity, change how much iron islands deliver to the ocean? And how might these changes affect marine ecosystems over time?

What’s clear is that the ocean’s nutrient cycles are more complex — and more fascinating — than they once appeared. Sometimes, the biggest discoveries come not from distant deserts or deep-sea vents, but from the land just beyond the horizon.

Research paper:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2025GL118095