Oil Field Pollution and Sea Ice Feedback Loops Are Speeding Up Arctic Warming, New Study Finds

The Arctic is warming faster than any other region on Earth, and new research shows that human activity and natural ice processes are working together to accelerate that change even more. A large international study has found that oil and gas emissions, combined with openings in sea ice, are triggering powerful feedback loops that rapidly alter atmospheric chemistry, boost cloud formation, and speed up sea-ice loss across the Arctic.

The findings come from a major field campaign led by scientists at Penn State University and several partner institutions, offering one of the most detailed looks yet at how industrial pollution and natural Arctic processes interact in the lower atmosphere.

A Closer Look at the Arctic’s Most Sensitive Layer

The study focused on the atmospheric boundary layer, the lowest part of the atmosphere that sits closest to Earth’s surface. This layer is critical because it is where air directly interacts with snow, ice, open water, and human-made pollution.

To understand what was happening there, researchers carried out a two-month-long field campaign between February 21 and April 16, 2022, operating out of Utqiaġvik, Alaska. The timing was deliberate. The campaign began shortly after the polar sunrise, a period when sunlight returns after months of darkness. This sudden exposure to ultraviolet radiation intensifies chemical reactions at the surface and in the air above it.

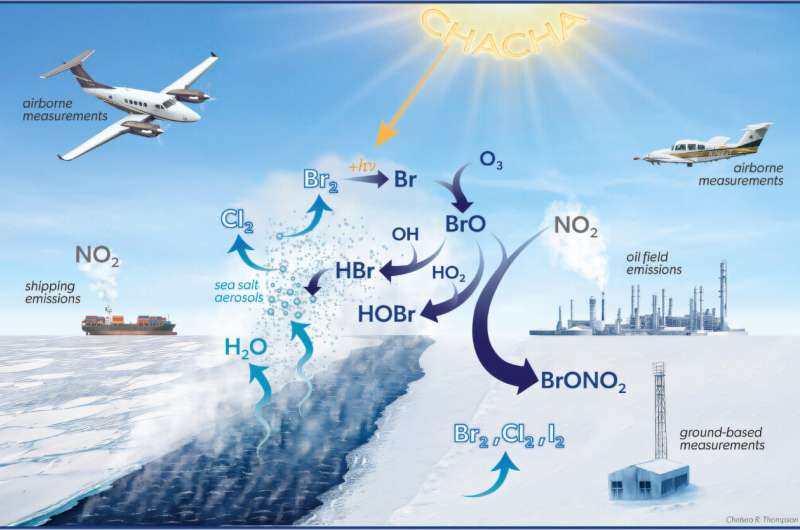

Scientists used two heavily instrumented aircraft along with ground-based sensors to sample air across a wide range of environments. These included snow-covered tundra, newly frozen sea ice, open water areas known as leads, and the Prudhoe Bay oil and gas fields, the largest oil extraction region in North America.

How Sea Ice Openings Change the Atmosphere

One of the study’s major findings involves leads, which are cracks or openings in sea ice that can range from just a few feet wide to several miles across. While these openings may seem small, their impact on the atmosphere is significant.

When extremely cold Arctic air moves over relatively warmer open water in a lead, intense evaporation occurs. This process forms swirling plumes of moisture and clouds, often referred to as sea smoke. These plumes act like vertical elevators, lifting water vapor, heat, aerosols, and chemical compounds hundreds of feet into the atmosphere.

The researchers found that this vertical transport dramatically alters atmospheric chemistry and cloud formation. The newly formed clouds trap heat and moisture, which leads to even more melting of sea ice. As the ice melts, more leads form, creating a self-reinforcing feedback loop that accelerates warming and sea-ice loss.

Oil Fields Are Changing Arctic Air Chemistry

The study also revealed that emissions from oil and gas extraction sites are measurably altering the Arctic atmosphere. Over the Prudhoe Bay oil fields, researchers detected major changes in air composition within the boundary layer.

Gas plumes released during extraction reacted rapidly in the cold Arctic air, leading to acidification of air masses and the formation of harmful chemical compounds. In some cases, pollution levels were comparable to those found in large urban centers.

One striking example involved nitrogen dioxide, a pollutant commonly associated with vehicle exhaust and industrial activity. During the campaign, nitrogen dioxide levels reached 60 to 70 parts per billion, concentrations similar to those observed during smog events in cities like Los Angeles.

This finding challenges the long-held assumption that the Arctic atmosphere is largely pristine and unaffected by industrial pollution.

Halogens, Snow, and Ozone Loss

Another critical discovery involved halogen chemistry, particularly the behavior of bromine in Arctic environments. Along the Arctic coastline, snowpacks often contain salt from seawater. When sunlight returns in spring, chemical reactions within these saline snowpacks release bromine into the air.

Bromine plays a powerful role in atmospheric chemistry. Once airborne, it rapidly destroys ozone in the boundary layer, a phenomenon unique to polar regions. Ozone normally helps absorb ultraviolet radiation, so when it is depleted, more solar energy reaches the surface.

This additional sunlight warms the snowpacks even further, releasing more bromine and reinforcing another positive feedback loop that contributes to surface warming and chemical instability in the Arctic atmosphere.

When Pollution and Natural Chemistry Combine

The study found that halogens like bromine don’t act alone. When they interact with oil field emissions, the chemistry becomes even more complex and concerning. Halogens can react with industrial plumes to produce free radicals, highly reactive molecules that drive further chemical reactions.

Some of the resulting compounds are relatively stable and can travel long distances, meaning pollution generated in one Arctic region can influence atmospheric conditions far beyond the oil fields themselves. This long-range transport raises concerns about broader regional and even global impacts.

Why These Feedback Loops Matter

The Arctic already experiences Arctic amplification, a phenomenon where warming occurs at two to four times the global average. The feedback loops identified in this study help explain why that amplification is happening so rapidly.

Cloud formation, sea-ice loss, pollution chemistry, and halogen reactions are all tightly linked. Once these processes begin reinforcing each other, they become extremely difficult to slow down. Importantly, many of these interactions are not fully represented in current climate models, meaning future warming may be underestimated.

What This Means for Climate Modeling and Policy

One of the main goals of the CHACHA project is to create high-quality datasets that climate modelers can use to improve predictions of Arctic and global climate change. By incorporating real-world observations of chemical reactions, cloud behavior, and pollution interactions, scientists hope to better estimate how quickly the Arctic will continue to warm.

The study also highlights the outsized influence of industrial activity in fragile environments. Even localized oil and gas operations can have far-reaching atmospheric effects when combined with Arctic-specific chemistry and meteorology.

Additional Context: Why the Arctic Is So Sensitive

The Arctic responds more strongly to change because of its ice-albedo effect. Ice reflects sunlight, while open water absorbs it. As sea ice melts, darker ocean surfaces absorb more heat, accelerating warming. Add cloud feedbacks and chemical reactions to the mix, and the system becomes even more sensitive.

Cold temperatures also slow the dispersion of pollutants, allowing chemicals to persist longer and react in unexpected ways. This makes the Arctic a unique and highly reactive environment compared to lower latitudes.

A Clearer Picture of a Rapidly Changing Region

This research provides one of the clearest pictures yet of how human emissions and natural Arctic processes are deeply intertwined. Rather than acting independently, oil field pollution, sea ice dynamics, cloud formation, and halogen chemistry combine to amplify warming in ways scientists are only beginning to fully understand.

As the Arctic continues to warm, studies like this underline the urgency of closely monitoring industrial activity and improving climate models to reflect the region’s complex reality.

Research paper:

https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/bams/106/11/BAMS-D-24-0192.1.xml