A Football-Field-Sized Balloon Is Flying Over Antarctica to Search for Dark Matter Clues

A massive scientific balloon, roughly the size of a football field, recently lifted off over Antarctica carrying an experiment designed to tackle one of the biggest unanswered questions in modern physics: what exactly is dark matter. The mission, known as the General AntiParticle Spectrometer (GAPS) experiment, launched on December 15 and is now floating about 24 miles above the Antarctic surface, where it will spend days to weeks collecting rare cosmic data.

This high-altitude balloon mission is part of an international scientific effort and includes major contributions from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, along with researchers from Columbia University, UCLA, Northeastern University, and partner institutions in Japan, Italy, and China. The project is supported by NASA’s long-duration balloon program, which uses Antarctica’s unique environment to enable extended scientific flights.

What the GAPS Experiment Is Trying to Do

At its core, GAPS is designed to search for rare forms of cosmic antimatter, specifically antiprotons and antideuterons. These particles are the antimatter counterparts of protons and deuterons and are extremely uncommon in nature. Scientists are especially interested in low-energy antideuterons, which are thought to be an exceptionally clean signal of possible dark matter interactions.

Dark matter itself is invisible and cannot be detected directly. Scientists only know it exists because of its gravitational influence on galaxies, galaxy clusters, and the large-scale structure of the universe. Current estimates suggest that dark matter makes up around 85% of all matter in the universe, yet its fundamental properties remain unknown.

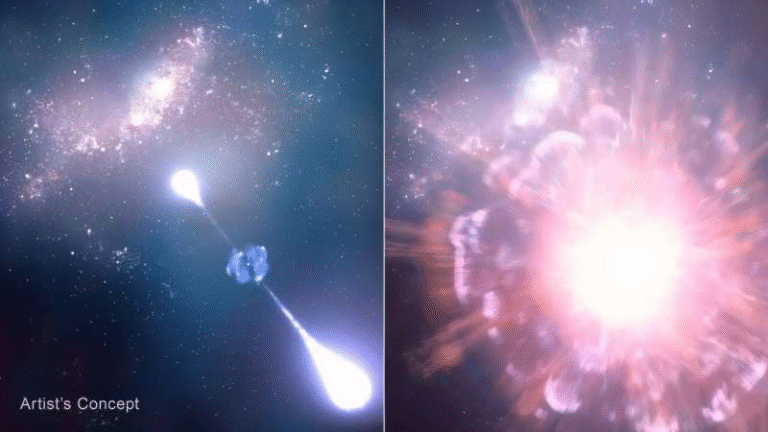

One leading idea is that dark matter particles may occasionally annihilate or decay, producing standard particles and antimatter in the process. If GAPS can detect antideuterons that cannot be easily explained by known astrophysical processes, it could provide strong indirect evidence about the nature of dark matter.

How the Balloon-Based Detector Works

Unlike traditional space telescopes or underground detectors, GAPS uses a novel detection technique specifically tailored for antimatter. Instead of relying on magnetic fields to bend particle trajectories, GAPS looks for what happens when antimatter slows down and interacts with ordinary matter inside the detector.

When an antimatter particle enters the GAPS instrument, it gradually loses energy and eventually gets captured by an atom in the detector material, forming what scientists call an exotic atom. This unstable atom emits characteristic X-rays as it de-excites, before finally annihilating and producing a cascade of secondary particles. By measuring these X-rays and annihilation products, GAPS can precisely identify the type of antimatter particle that entered the detector.

The experiment combines a time-of-flight system, which measures particle velocity, with a silicon detector array that tracks energy deposition and annihilation signatures. This approach allows GAPS to distinguish rare antimatter signals from the much more common background of ordinary cosmic rays.

Why Antarctica Is the Perfect Place for This Mission

Antarctica plays a critical role in missions like GAPS. During the austral summer, the Sun remains above the horizon almost continuously, providing stable power conditions for solar-powered scientific balloons. Even more importantly, the strong, circular stratospheric wind patterns over Antarctica allow balloons to travel around the continent multiple times without drifting too far off course.

Flying at an altitude of about 120,000 feet (36 kilometers) places the experiment above most of Earth’s atmosphere. This dramatically reduces interference from atmospheric particles and allows the detector to observe primary cosmic rays with much greater clarity than ground-based experiments.

NASA has a long history of using Antarctic balloon launches for astrophysics, particle physics, and cosmology experiments, and GAPS builds on decades of experience with these platforms.

The Role of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa have played a leading role in the development and operation of GAPS. Their contributions include detector calibration, instrument integration, and flight operations. Members of the UH team have been deeply involved throughout the project’s multi-year preparation phase, including challenging periods during the COVID-19 pandemic when much of the detector development had to be adapted to restricted conditions.

The involvement of graduate students and early-career researchers has also been a key part of the project, highlighting the educational value of large-scale experimental physics missions alongside their scientific goals.

Why Antimatter Matters in the Dark Matter Search

Antimatter is produced naturally in high-energy environments, such as supernova explosions and collisions between cosmic rays and interstellar gas. However, these processes tend to produce antimatter at higher energies than what GAPS is optimized to detect.

Low-energy antideuterons are especially interesting because known astrophysical sources are expected to produce them in vanishingly small numbers. This makes any potential detection by GAPS particularly significant, as it could point toward non-standard sources, including dark matter interactions.

Previous experiments, such as the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS-02) on the International Space Station, have measured cosmic antiprotons with high precision. GAPS complements these efforts by focusing on a different energy range and particle type, providing an independent and highly sensitive probe of dark matter models.

A Broader Context in Modern Physics

The search for dark matter is happening on many fronts at once. Underground detectors look for direct collisions between dark matter and atomic nuclei. Particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider attempt to create dark matter particles in high-energy collisions. Astrophysical experiments, including GAPS, focus on indirect detection by observing the products of dark matter interactions in space.

Balloon-based experiments occupy a unique niche in this landscape. They are far less expensive than satellites, can be recovered and upgraded between flights, and still provide access to near-space conditions. This flexibility makes them ideal for testing innovative ideas and technologies, such as the exotic atom technique used by GAPS.

What Comes Next for GAPS

The current Antarctic flight represents a major milestone, but it is not the end of the project. Data collected during the mission will be carefully analyzed over the coming years to search for statistically significant antimatter signals. Depending on the results, future flights may follow, with improved detector configurations and longer observation times.

Even if no antideuterons are detected, the experiment will still place important constraints on theoretical dark matter models, helping physicists narrow down which ideas remain viable.

Why This Mission Matters

The GAPS balloon mission is a reminder that some of the most profound scientific questions can be explored with surprisingly elegant tools. By combining a massive balloon, a carefully designed detector, and the extreme environment of Antarctica, scientists are pushing the boundaries of what can be measured from near space.

Whether or not GAPS finds direct hints of dark matter, it represents a bold and creative approach to understanding what most of the universe is made of, and it adds a crucial piece to the global effort to solve one of physics’ deepest mysteries.

Research reference:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.01301