Scientists Reveal How Microbes Rapidly Colonize Fresh Lava After Volcanic Eruptions

Life has a remarkable ability to establish itself even in the most extreme and seemingly uninhabitable environments. A new scientific study shows just how quickly and predictably microscopic life forms begin colonizing freshly formed lava after volcanic eruptions, offering rare insight into one of ecology’s least understood processes: primary succession, or life starting from absolute scratch.

The research focuses on lava flows from the Fagradalsfjall volcano in Iceland, which erupted multiple times between 2021 and 2023. These eruptions created a unique natural experiment. Each lava flow emerged at temperatures exceeding 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, meaning the rock was completely sterile at the moment it erupted. Once cooled, however, it became an ideal surface for scientists to study how life begins anew on a clean slate.

The study was led by researchers from the University of Arizona, combining expertise from ecology, microbiology, and planetary science. By observing three separate eruptions in the same location over three years, the team achieved something exceptionally rare in natural sciences: a triplicate experiment in a real-world environment.

Why Fresh Lava Is a Perfect Natural Laboratory

Fresh lava is among the most extreme environments on Earth. It contains no organic material, holds very little water, and is constantly exposed to harsh weather. These conditions make it one of the lowest-biomass habitats on the planet, comparable to places like Antarctica or the Atacama Desert.

Because the lava begins completely lifeless, scientists can rule out lingering organisms and instead focus entirely on where new microbes come from, how fast they arrive, and which ones survive.

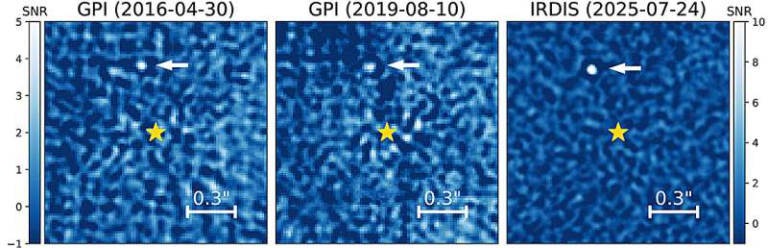

To capture this process in detail, the research team collected samples from lava flows at different stages, including rock that had cooled just hours earlier. They also gathered rainwater, airborne particles known as aerosols, surrounding soil, and nearby rocks. By comparing all of these sources, they could trace the origins of the microbes that eventually settled on the lava.

How Microbes Arrive on Brand-New Lava

Using DNA sequencing, along with advanced statistical modeling and machine learning, the researchers identified which organisms appeared on the lava and where they likely came from.

The results showed a clear pattern. In the earliest stages, microbes primarily arrived via wind-blown soil particles and aerosols drifting through the air. These microscopic passengers settled onto the lava surface soon after it cooled.

Over time, however, rainwater became the dominant source of new microbes. Rain is far from sterile; it carries bacteria and other microorganisms that originate in the atmosphere, sometimes attached to dust particles. These microbes can even play a role in cloud formation by acting as condensation nuclei.

This shift toward rainwater as the main delivery system became especially clear after the lava experienced its first winter.

A Boom, a Bust, and Then Stability

During the first year following an eruption, microbial diversity increased steadily. New species arrived, and the ecosystem began to develop. However, after the first winter season, diversity dropped sharply.

This decline appears to be caused by environmental filtering. Iceland’s winters are harsh, and only a subset of extremely resilient microbes can survive repeated freezing, drying, and nutrient scarcity. Once those survivors established themselves, the microbial community became more stable.

With each additional winter, there was less turnover in species. Instead of constant change, the ecosystem settled into a more predictable structure. The same patterns appeared across all three eruptions, reinforcing the idea that microbial colonization of lava follows consistent and repeatable rules.

The Toughest Microbes Move in First

The earliest colonizers are organisms capable of surviving extreme stress. These microbes tolerate low water availability, intense temperature swings, and minimal nutrients. Even when rain falls, lava surfaces dry out rapidly, creating a hostile environment for most life.

Despite these challenges, single-celled organisms establish themselves surprisingly fast. Their presence lays the groundwork for future ecological development, gradually transforming barren rock into a surface capable of supporting more complex life.

Why This Study Is Different From Past Research

Most previous studies of volcanic ecosystems focused on secondary succession, where plants and microbes return to land that previously supported life. This research, by contrast, examined primary microbial succession, meaning life moving into an environment that had never been inhabited before.

Another key difference is timing. Many earlier studies analyzed lava months or even years after an eruption. In this case, samples were taken as soon as the lava cooled, capturing the very earliest stages of colonization.

The extended timeline of three years allowed researchers to observe not just initial arrival, but also seasonal changes, survival patterns, and long-term stabilization. Few natural studies have this level of resolution.

What Lava Flows Can Teach Us About Earth’s Past

Understanding how microbes colonize lava helps scientists reconstruct how life may have spread across early Earth, when volcanic activity was far more common. Large areas of the planet were once covered in fresh basalt, similar to modern lava fields.

Microbes capable of colonizing such environments likely played a key role in shaping early ecosystems, gradually contributing organic material and altering rock surfaces in ways that made them more hospitable for future life forms.

Implications for Mars and Other Worlds

One of the most exciting aspects of this research lies beyond Earth. Much of Mars’ surface is basaltic, shaped by ancient volcanic activity. Although volcanism on Mars has largely subsided, past eruptions could have created temporary habitable conditions by releasing heat, gases, and possibly melting subsurface ice.

By understanding how microbes colonize lava on Earth, scientists gain clues about where to search for biosignatures on Mars and how life, if it ever existed there, might have taken hold.

The findings also help researchers think more clearly about how volcanism influences habitability on other rocky planets and moons throughout the solar system.

The Bigger Picture of Microbial Life

Microbes are often overlooked, but they are foundational to nearly every ecosystem on Earth. They influence soil formation, nutrient cycling, and even weather patterns through their interactions with the atmosphere.

This study highlights just how adaptable microbial life can be and how quickly it responds to new opportunities. From a sterile slab of volcanic rock to a stable microbial community, the process unfolds faster and more predictably than scientists once believed.