Astronomers Create the First Detailed Map of the Sun’s Outer Boundary

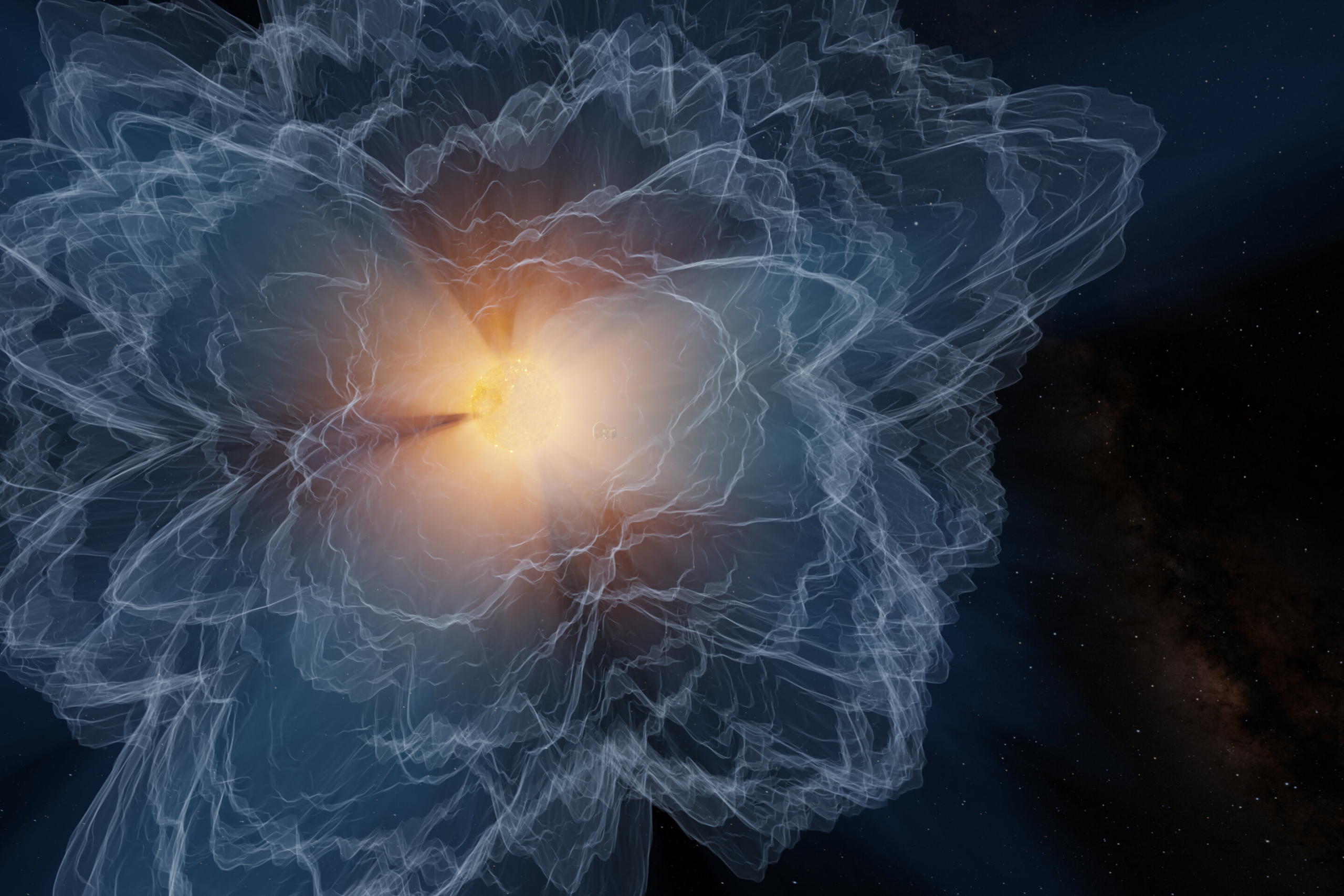

Astronomers have reached a major milestone in solar science by producing the first continuous, two-dimensional map of the Sun’s outer atmospheric boundary. This boundary, known as the Alfvén surface, marks the point where material escaping from the Sun becomes the solar wind and can no longer be pulled back by the Sun’s magnetic field. In simple terms, it is the true outer edge of the Sun’s atmosphere, and until now, it had never been mapped in detail.

The research was carried out by scientists from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) and published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. By combining remote observations with direct spacecraft measurements, the team was able to not only locate this boundary accurately but also track how it changes as the Sun moves through its activity cycle.

At the heart of this work is a better understanding of how the Sun interacts with the rest of the solar system, including Earth. Since solar activity affects satellites, astronauts, power grids, and communication systems, knowing where and how the solar wind forms is far more than an academic exercise.

Understanding the Alfvén Surface and Why It Matters

The Alfvén surface is defined as the region in the Sun’s atmosphere where the speed of the outward-flowing solar wind becomes faster than the speed at which magnetic waves can travel back toward the Sun. Inside this boundary, the Sun’s magnetic field dominates and can still influence plasma motion. Beyond it, the solar wind escapes freely into interplanetary space.

This boundary is often described as the “point of no return” for solar material. Once particles cross it, they are effectively cut off from the Sun and become part of the solar wind that fills the solar system. Despite its importance, scientists previously had to rely on indirect estimates and models to guess where this surface was located.

What makes the Alfvén surface especially interesting is that it is not smooth or fixed. It is dynamic, constantly reshaping itself as solar conditions change. Mapping it accurately gives scientists a powerful tool for studying how energy and particles move through the Sun’s outer atmosphere, also known as the corona.

How Scientists Mapped the Sun’s Outer Boundary

To create this groundbreaking map, researchers used a multi-spacecraft approach. The most crucial contributor was NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, the first spacecraft designed to fly directly through the Sun’s outer atmosphere. Parker repeatedly dives closer to the Sun than any mission before it, gathering direct measurements from regions humans had never explored.

The team relied heavily on data from Parker’s Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP) instrument, which measures the speed, density, and temperature of charged particles. SWEAP was developed by the CfA in collaboration with the University of California, Berkeley.

In addition to Parker, scientists incorporated observations from spacecraft located much farther away, including NASA’s Wind mission near Earth and the Solar Orbiter, a joint project of NASA and the European Space Agency. By comparing close-up measurements with distant solar wind data, the researchers were able to identify patterns that revealed where the Alfvén surface must lie.

This technique allowed them to build continuous, two-dimensional maps of the boundary rather than relying on isolated data points. Most importantly, Parker’s direct crossings of the Alfvén surface confirmed that the maps were accurate.

What the Maps Reveal About Solar Activity

One of the most important findings from this work is how dramatically the Alfvén surface changes over time. Scientists already suspected that the boundary shifts with the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle, but this study provided the first direct confirmation of what those changes actually look like.

During periods of high solar activity, known as solar maximum, the Alfvén surface moves farther away from the Sun. It also becomes larger, rougher, and more spiky, rather than forming a smooth shell. These irregular structures reflect the complex magnetic environment created by sunspots, solar flares, and active regions.

During solar minimum, when the Sun is calmer, the boundary contracts closer to the Sun and appears smoother and more uniform. The new maps show these transitions clearly, allowing scientists to match large-scale changes with detailed measurements taken deep inside the Sun’s atmosphere.

These observations confirm long-standing theoretical predictions and give researchers confidence that their models of solar behavior are on the right track.

Why Parker Solar Probe Is So Important

The success of this research is closely tied to the unique capabilities of the Parker Solar Probe. Unlike previous missions that observed the Sun from a safe distance, Parker was designed to fly directly into the region where the solar wind is born.

With each orbit, the spacecraft ventures deeper into the Sun’s atmosphere, repeatedly crossing the Alfvén surface. This makes it possible to test theories against real data rather than assumptions. As the Sun continues moving through its current activity cycle, Parker will observe how the boundary evolves in real time.

The mission is expected to become even more valuable as the Sun approaches future phases of its cycle, especially the next solar minimum. Scientists plan to use Parker’s data to study how the corona changes over an entire solar cycle, something that has never been done before.

Implications for Earth and Space Weather

Understanding where and how the solar wind forms has direct consequences for space weather forecasting. Solar wind streams interact with Earth’s magnetic field, triggering geomagnetic storms that can disrupt satellites, GPS signals, radio communications, and even power grids.

Better maps of the Alfvén surface allow scientists to improve models that predict how solar activity travels through space. This leads to more accurate forecasts and better preparation for potentially damaging solar events.

The findings also help answer fundamental questions about why the Sun’s corona is millions of degrees hotter than its surface, a mystery that has puzzled scientists for decades. Studying the region below and around the Alfvén surface offers clues about how energy is transferred and dissipated in the Sun’s atmosphere.

What This Means for Other Stars

While this research focuses on our Sun, its implications go far beyond the solar system. Many stars produce stellar winds similar to the solar wind, and these winds play a key role in shaping planetary environments.

By understanding how the Alfvén surface behaves around the Sun, scientists can apply similar principles to other stars. This helps researchers study stellar evolution, magnetic activity, and even the habitability of exoplanets, since strong stellar winds can strip atmospheres from nearby planets.

The coordinated, multi-spacecraft method used in this study is likely to become a model for future research in heliophysics and stellar science.

Looking Ahead

This first detailed map of the Sun’s outer boundary opens the door to a new era of solar exploration. With Parker Solar Probe continuing its close encounters and other spacecraft providing broader context, scientists now have the tools to watch the Sun’s atmosphere evolve with unprecedented clarity.

As solar observations become more precise, our understanding of how the Sun influences the solar system—and life on Earth—will continue to deepen.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ae0e5c