JWST Reveals a Hidden Supermassive Black Hole Inside an Ordinary-Looking Early Galaxy

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have uncovered a remarkable object from the early universe that is forcing scientists to rethink how supermassive black holes formed. The galaxy, known as Virgil, existed just 800 million years after the Big Bang, yet it already hosted a powerful black hole at its center—one that had remained hidden in plain sight.

At first glance, Virgil looks unremarkable. In ultraviolet and visible light, it appears to be a fairly typical young galaxy, steadily forming stars like many others from that era. But when astronomers observed it using infrared wavelengths, an entirely different picture emerged. Beneath layers of cosmic dust lies an extremely active, rapidly growing supermassive black hole, pumping out enormous amounts of energy while remaining invisible to traditional observations.

This dramatic contrast has earned Virgil the reputation of a cosmic “Jekyll and Hyde” galaxy and has major implications for our understanding of the infant universe.

A Galaxy That Changes Personality With Wavelength

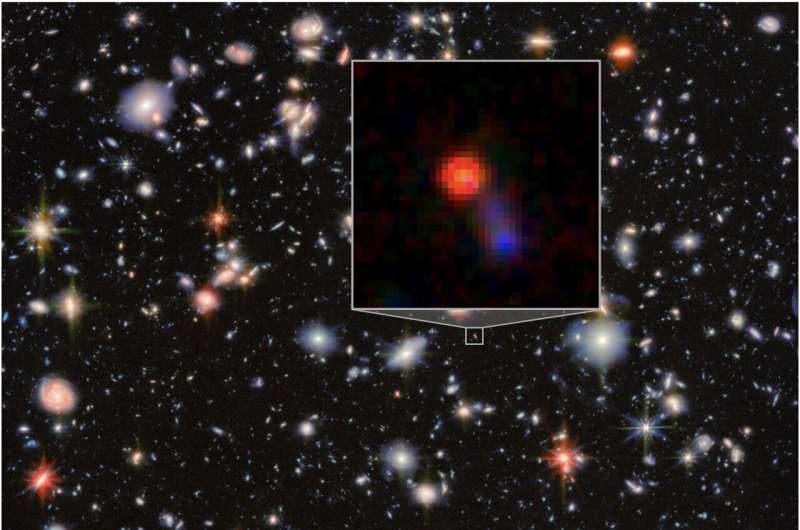

Virgil was observed in a region of the sky already famous among astronomers: the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field, a tiny patch of sky that has revealed thousands of distant galaxies. JWST revisited this same region over the course of three years, using its advanced instruments to study the early universe in unprecedented detail.

When astronomers analyzed data from JWST’s Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), Virgil appeared to be a normal star-forming galaxy. Its ultraviolet and optical light showed no obvious signs of extreme activity at its core. Under these observations alone, Virgil would have been classified as ordinary.

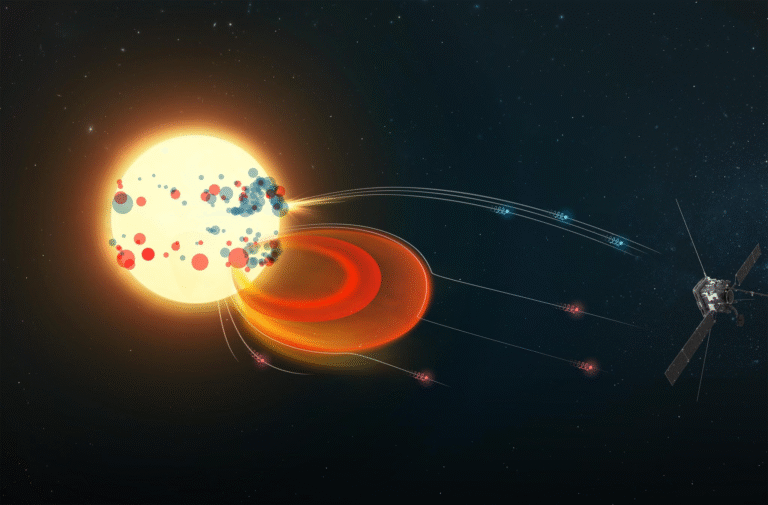

The breakthrough came when researchers included data from JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). MIRI detects longer wavelengths of light that can pass through thick dust clouds. Once these observations were added, Virgil’s true nature became clear: the galaxy hosts a heavily obscured active galactic nucleus, powered by a supermassive black hole accreting material at an extraordinary rate.

This transformation from a calm, star-forming galaxy into a dust-enshrouded cosmic powerhouse highlights just how deceptive early galaxies can be when viewed through a limited range of wavelengths.

An Overmassive Black Hole That Breaks the Rules

One of the most striking aspects of Virgil is the disproportionate size of its black hole. Based on the infrared data, the inferred black hole mass is far larger than expected for a galaxy of Virgil’s size and age. This places it among a growing group of so-called overmassive black holes found in the early universe.

For decades, astronomers believed that galaxies formed first and gradually nurtured black holes in their centers, with both growing together in a relatively balanced way. Virgil challenges that idea. In this case, the black hole appears to have grown faster than its host galaxy, suggesting that black hole formation may sometimes lead, rather than follow, galaxy growth.

This discovery adds to a growing body of evidence from JWST that many early black holes were already massive and active long before their galaxies fully matured.

Part of the Mysterious “Little Red Dots” Population

Virgil belongs to a puzzling group of objects known as Little Red Dots (LRDs). These are compact, extremely red sources discovered by JWST at very high redshifts. Their red color comes from a combination of cosmic expansion, which stretches light to longer wavelengths, and dust obscuration, which hides energetic processes from view.

LRDs appeared in significant numbers around 600 million years after the Big Bang and then largely disappeared by about 1.5 billion years after the universe formed. Their true nature has been debated, with explanations ranging from intense star formation to more exotic physical processes.

Virgil stands out as the reddest object among all known Little Red Dots. The confirmation that it hosts a dust-obscured supermassive black hole strongly supports the idea that at least some LRDs are early active galactic nuclei hiding behind thick veils of dust.

If Little Red Dots were once common, their descendants must still exist today. Understanding what they evolved into could help astronomers connect the early universe to the galaxies we see around us now.

Why JWST’s Mid-Infrared Vision Is Crucial

Virgil’s discovery would not have been possible without JWST’s mid-infrared capabilities. Dust absorbs ultraviolet and optical light, effectively concealing black hole activity. Mid-infrared light, however, reveals the heat produced when dust is energized by intense radiation from an accreting black hole.

This means that many early galaxies observed only with near-infrared instruments could be misclassified. Without deep MIRI observations, astronomers may be systematically overlooking a hidden population of dust-obscured black holes.

The challenge is that MIRI observations require long exposure times, making them costly in terms of telescope resources. As a result, many large JWST surveys rely on deep near-infrared imaging but only shallow mid-infrared data. Virgil demonstrates that this strategy may miss some of the most extreme objects in the early universe.

Implications for Cosmic Reionization

The discovery of Virgil also raises important questions about cosmic reionization, a key phase in early cosmic history that occurred roughly 100 to 200 million years after the Big Bang. During this period, the universe transitioned from being filled with neutral hydrogen to one dominated by ionized gas, allowing light to travel freely through space.

While early stars are thought to have played a major role in reionization, energetic black holes like Virgil could have contributed significantly as well. If many dust-obscured black holes existed during this era, their combined energy output may have influenced how quickly and efficiently the universe became reionized.

The fact that no other object quite like Virgil has yet been identified at such early times may reflect observational limits rather than true rarity. Deeper and wider mid-infrared surveys could reveal many more similar galaxies.

A New Direction for Black Hole Research

Virgil represents a turning point in how astronomers study the early universe. It shows that some of the most extreme black holes were hiding inside galaxies that looked completely normal, and that only the right tools can expose their true nature.

As JWST continues its mission, astronomers plan to conduct deeper mid-infrared observations over larger areas of the sky. These efforts will determine whether Virgil is an outlier or simply the first clearly identified member of a much larger hidden population.

What is becoming increasingly clear is that the early universe was far more complex—and far more energetic—than previously imagined.

Research Paper:

Deciphering the Nature of Virgil: An Obscured Active Galactic Nucleus Lurking within an Apparently Normal Lyα Emitter during Cosmic Reionization, The Astrophysical Journal (2025)

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ae089c