Parker Solar Probe Reveals That Some Solar Wind Makes a Surprising U-Turn Back to the Sun

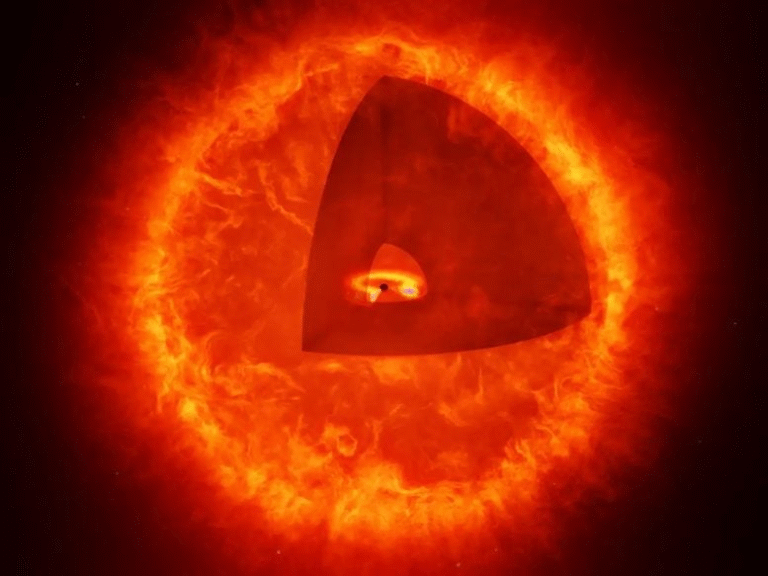

Images from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, captured during its record-breaking close pass by the Sun in December 2024, have revealed something scientists long suspected but had never seen in such striking detail: not all solar material blasted outward during a solar eruption actually escapes into space. Some of it turns around and falls back toward the Sun, reshaping the solar atmosphere and influencing future solar activity in ways that directly affect space weather across the solar system.

The new observations come from Parker Solar Probe’s closest-ever encounter with the Sun, when the spacecraft skimmed just 3.8 million miles (about 6 million kilometers) above the solar surface. At that distance, Parker was flying through the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona, giving scientists an unprecedented front-row view of how the Sun’s magnetic fields behave during massive eruptions.

What Parker Solar Probe Saw During Its Historic Flyby

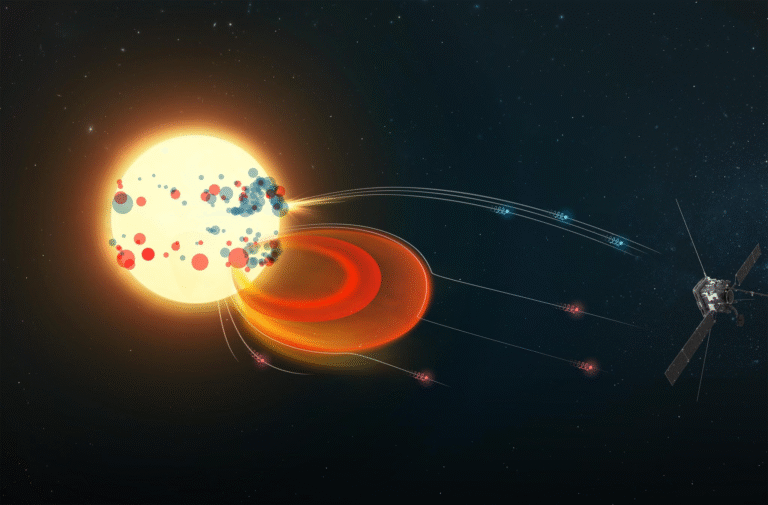

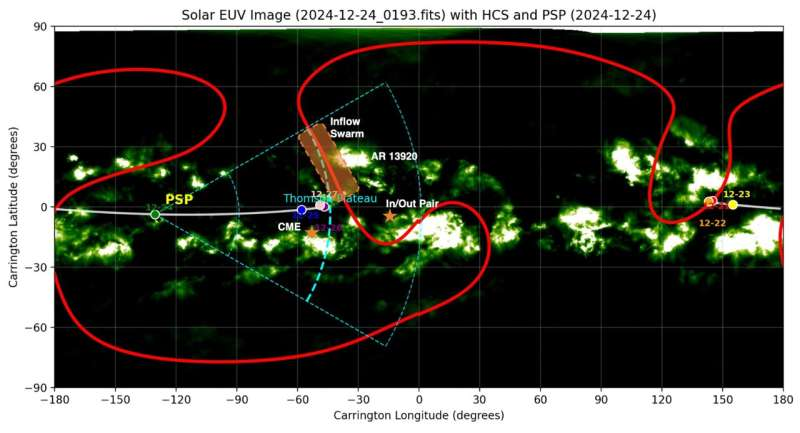

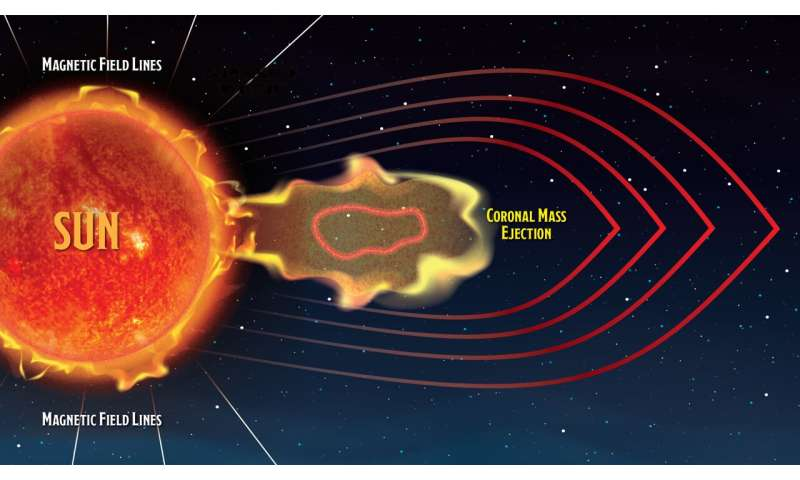

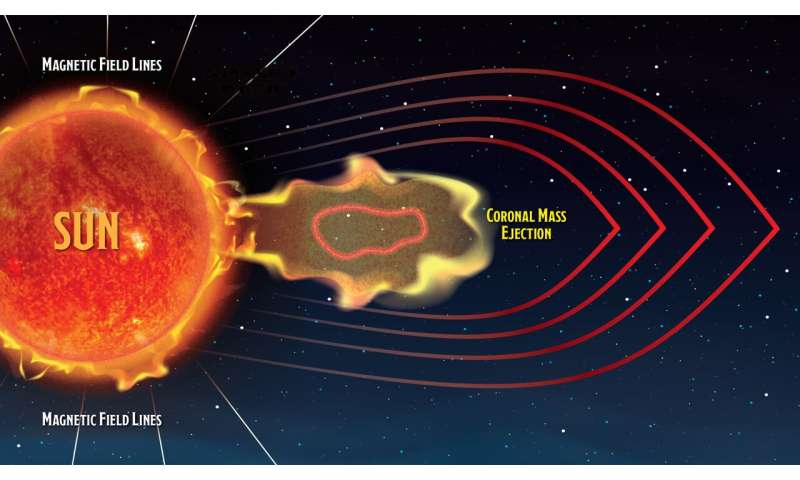

As Parker Solar Probe swept through the corona on December 24, 2024, its Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe (WISPR) observed a coronal mass ejection, or CME, erupting from the Sun. CMEs are enormous explosions that fling billions of tons of magnetized plasma into space at millions of kilometers per hour. They are one of the main drivers of space weather, capable of disrupting satellites, GPS systems, radio communications, and even power grids on Earth.

What made this particular CME special was what happened after the eruption. In the CME’s wake, WISPR detected elongated blobs of solar material moving back toward the Sun, rather than continuing outward into space. These features are known as inflows, and while they have been hinted at in past observations from missions like SOHO and STEREO, Parker Solar Probe captured them from inside the solar atmosphere, revealing fine-scale details never seen before.

This close-up view allowed scientists to precisely measure the size, structure, and speed of the inflowing material, turning what was once a distant curiosity into a well-documented physical process.

How Solar Wind Can Reverse Direction

To understand why some solar material makes a U-turn, it helps to look at how CMEs form. These eruptions are usually triggered by twisted magnetic field lines in the Sun’s corona. When these magnetic structures become unstable, they snap and reconnect in a violent process called magnetic reconnection. This sudden reconfiguration releases vast amounts of energy, hurling plasma and magnetic fields outward as a CME.

Credit: NASA

Credit: NASA

Credit: NASA

Credit: NASA

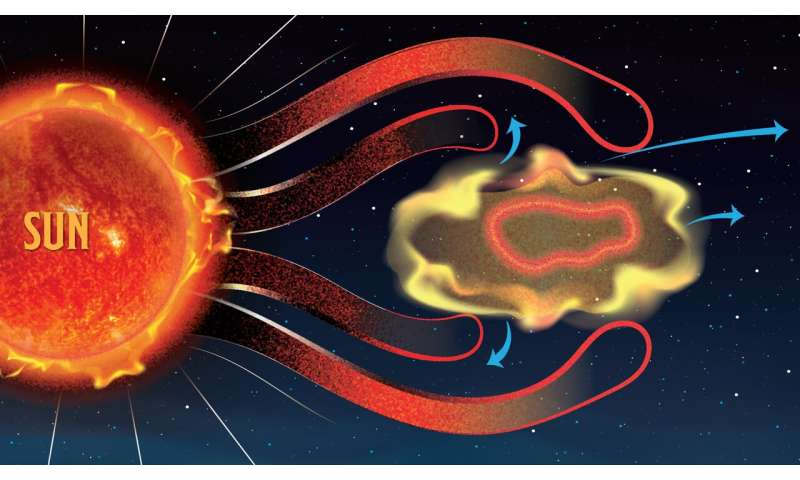

As the CME expands, it pushes against surrounding magnetic field lines. In some cases, those nearby field lines stretch so far that they tear apart, similar to fabric pulled too tightly. When the magnetic field reconnects again, it forms new magnetic loops. Some of these loops open outward into space, allowing solar wind to escape. Others, however, remain connected to the Sun at both ends, guiding plasma back down toward the solar surface.

The result is an inflow: solar material that initially moved outward during the eruption is pulled back along reconnected magnetic field lines, creating the dramatic “U-turn” seen in Parker’s images.

Why These Inflows Matter for the Sun and the Solar System

One of the most important findings from these observations is that not all magnetic energy released during a CME permanently leaves the Sun. Instead, some of it lingers, contracts, and eventually returns, subtly reshaping the Sun’s magnetic environment.

As inflows collapse back toward the Sun, they drag nearby solar material with them and interact with magnetic fields deeper in the corona. This process can alter the local magnetic landscape, which in turn may influence how and where the next CME erupts.

Even small changes matter. A shift of just a few degrees in the direction of a CME can be the difference between it slamming into a planet like Earth or Mars, or missing it entirely. From a space weather forecasting perspective, understanding these magnetic adjustments is critical.

A New Level of Detail From Inside the Corona

Previous missions observed inflows from millions of miles away, making it difficult to determine their true structure or behavior. Parker Solar Probe’s extreme proximity changed that completely. The spacecraft provided high-resolution images that revealed individual blobs of material, their trajectories, and their motion through the corona.

These observations confirmed that inflows are not rare oddities but a natural and recurring part of CME evolution. They also showed that magnetic recycling is an active, ongoing process, not just a theoretical possibility.

By directly imaging these processes, Parker has given scientists a clearer picture of how the Sun manages its magnetic energy, continuously ejecting and reclaiming material as part of its normal activity cycle.

What This Means for Space Weather Prediction

Space weather forecasting relies heavily on understanding how solar eruptions form and propagate through space. Until now, many models assumed that once magnetic fields and plasma were ejected during a CME, they were effectively gone.

The discovery that some of this material returns and reshapes the corona means that models need to account for this recycling process. Incorporating inflows into simulations could improve predictions of CME trajectories, timing, and intensity, potentially allowing for earlier and more accurate warnings of hazardous space weather events.

This has practical implications not just for Earth, but also for the Moon, Mars, and future human missions beyond low Earth orbit.

Parker Solar Probe’s Role Going Forward

Parker Solar Probe is still in the middle of its mission, with more close passes planned as the Sun gradually moves from solar maximum toward solar minimum. Each encounter provides a new opportunity to observe how the Sun’s magnetic environment changes over time.

As solar activity declines, scientists expect the structure of the corona and the behavior of CMEs to evolve, possibly revealing even more dramatic examples of magnetic reconnection and recycling. With every pass, Parker helps build a more complete picture of how the Sun works, from its surface to the edge of interplanetary space.

A Broader Look at Coronal Mass Ejections

CMEs are among the most powerful events in the solar system, capable of releasing energy equivalent to billions of nuclear bombs. They are a natural part of the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle, becoming more frequent during periods of high solar activity.

Understanding how CMEs interact with the Sun’s magnetic field is essential not only for space weather forecasting but also for fundamental solar physics. The Parker Solar Probe findings show that CMEs are not simple one-way explosions, but complex events involving feedback, recycling, and ongoing magnetic evolution.

Why This Discovery Is a Big Deal

Seeing solar wind make a U-turn back to the Sun may sound subtle, but it fundamentally changes how scientists think about the solar atmosphere. The Sun is not just shedding material into space; it is constantly reworking its own magnetic structure, with each eruption influencing the next.

Thanks to Parker Solar Probe, scientists now have direct evidence of this process happening in real time, at scales and resolutions never achieved before. It’s a reminder that even our closest star still has plenty of surprises left.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ae0d7d