Scientists Find That Most Geostationary Satellites Barely Leak Radio Signals That Could Disrupt Astronomy

Radio astronomy is facing a growing challenge, and it has nothing to do with distant galaxies or mysterious cosmic phenomena. Instead, the problem is much closer to home. Human-made satellites, built to power global communications, are increasingly crowding the radio spectrum that astronomers depend on to study the universe. A new scientific study has now taken a close look at satellites orbiting 36,000 kilometers above Earth to find out just how much unintended radio noise they are producing—and the results are cautiously reassuring.

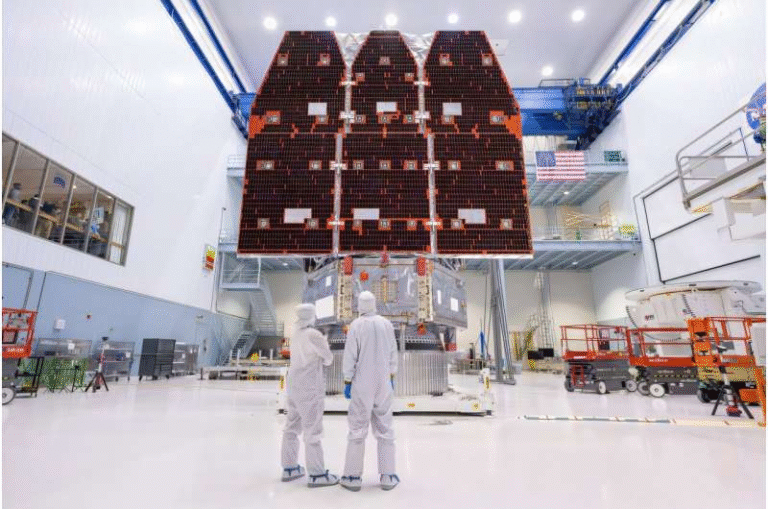

For years, concerns about satellite interference have focused mainly on low Earth orbit (LEO) constellations such as SpaceX’s Starlink, which zip across the sky in minutes and have been shown to emit radio signals that interfere with astronomical observations. However, hundreds of satellites operate much farther away in geostationary orbit, and until recently, no one had systematically checked whether these distant spacecraft were quietly leaking radio emissions into sensitive astronomical frequency bands.

That gap has now been filled by a research team led by scientists from CSIRO’s Astronomy and Space Science division in Australia.

Why Geostationary Satellites Are Special

Geostationary satellites orbit Earth at an altitude of roughly 36,000 kilometers, moving at exactly the same rotational speed as the planet. From the ground, they appear fixed in a single position in the sky. This makes them ideal for tasks such as television broadcasting, weather monitoring, data relay, and military communications.

For radio astronomers, this stationary nature is a double-edged sword. Unlike low-orbit satellites that quickly pass through a telescope’s field of view, a geostationary satellite can sit in the same observing area for hours at a time. If such a satellite were emitting unintended radio signals, even weak ones, the prolonged exposure could seriously contaminate astronomical data.

Despite these concerns, geostationary satellites had largely escaped scrutiny—until now.

How the Study Was Conducted

The research team analyzed archival data from 2020 collected by the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA), a powerful low-frequency radio telescope located in a radio-quiet region of Western Australia. The data came from the GLEAM-X survey, which observes the sky across frequencies ranging from 72 to 231 megahertz.

This frequency range is particularly important because it overlaps with the operating band of the upcoming Square Kilometre Array (SKA-Low), which will soon become the most sensitive low-frequency radio telescope ever built.

Using precise orbital predictions, the researchers tracked up to 162 geostationary and geosynchronous satellites during a single night of observations. Instead of looking for obvious signals from individual images, they employed a technique called image stacking, combining data at each satellite’s predicted position over time. This method allows astronomers to detect extremely faint signals that would otherwise remain hidden.

What the Researchers Found

The findings were largely encouraging.

For the vast majority of satellites, the team detected no unintended radio emissions within the studied frequency range. In technical terms, they were able to place upper limits on the satellites’ radio leakage, with most limits falling below 1 milliwatt of equivalent isotropic radiated power (EIRP) across a 30.72 megahertz bandwidth. In the best cases, the limits were as low as 0.3 milliwatts, an impressively small amount of power.

Only one satellite, Intelsat 10–02, showed a possible detection of unintended emission, estimated at around 0.8 milliwatts. Even this potential signal was extremely weak and far below the levels commonly observed from many low Earth orbit satellites, which can emit hundreds of times more power in similar frequency bands.

Distance plays a major role here. Geostationary satellites are about ten times farther away than the International Space Station and most LEO spacecraft. Because radio signals weaken rapidly with distance, even relatively strong emissions from geostationary orbit fade to near invisibility by the time they reach Earth-based telescopes.

Why These Results Matter for the Future

At present, instruments like the Murchison Widefield Array can safely ignore most geostationary satellites when observing low-frequency radio waves. However, the situation becomes more complicated when considering the future.

The Square Kilometre Array, currently under construction in Australia and South Africa, will be orders of magnitude more sensitive than existing telescopes. Signals that are harmless background noise today could become serious sources of interference tomorrow. This is why the new measurements are so important—they provide a baseline for predicting how satellite emissions might affect next-generation observatories.

The study also highlights an uncomfortable reality: even satellites designed to avoid protected astronomical frequencies can still leak radio energy. These unintended emissions may come from onboard electronics, solar panels, power systems, or computer hardware, rather than from communication transmitters themselves.

Understanding Radio Astronomy and Interference

Radio astronomy relies on detecting extremely faint natural signals, often billions of times weaker than everyday radio transmissions on Earth. Frequencies below a few hundred megahertz are especially valuable because they allow scientists to study the early universe, cosmic magnetic fields, and the distribution of hydrogen across space.

Unfortunately, these same frequencies are increasingly attractive for human technology. As satellite traffic grows and space becomes more crowded, maintaining radio-quiet environments is becoming harder. Remote locations like the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory were chosen precisely because they are shielded from terrestrial interference—but satellites orbiting overhead bypass those protections entirely.

A Cautious Sense of Optimism

For now, geostationary satellites appear to be relatively polite neighbors in the low-frequency radio spectrum. Compared to their low-orbit counterparts, they pose a much smaller risk to radio astronomy, at least within the 72–231 megahertz range examined in this study.

Still, researchers stress that this situation could change. Satellite technology is evolving rapidly, and the number of spacecraft in orbit continues to rise. What is quiet today may not remain quiet forever.

The new study represents an important step toward understanding and managing the growing tension between space-based infrastructure and scientific exploration. As telescopes become more sensitive and satellites more numerous, cooperation between astronomers, engineers, and regulators will be essential to preserve humanity’s ability to listen to the faint whispers of the universe.

Research paper:

Limits on Unintended Radio Emission from Geostationary and Geosynchronous Satellites in the SKA-Low Frequency Range

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.07341