Radio Telescopes Find No Sign of a Black Hole at the Heart of Omega Centauri

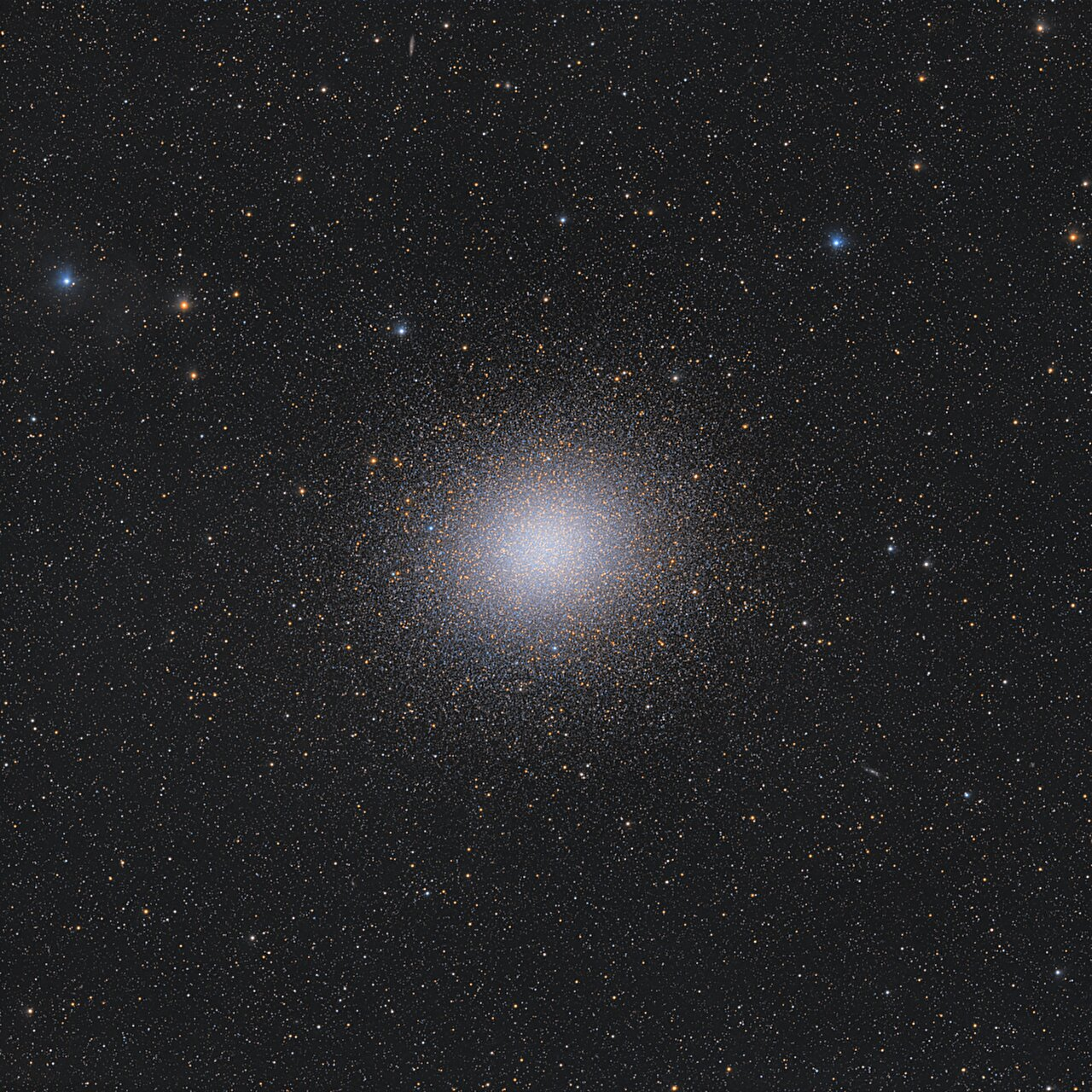

Omega Centauri dominates the southern sky as the largest and brightest globular cluster in the Milky Way, containing an estimated 10 million stars packed into a dense, spherical structure. For decades, astronomers have studied this extraordinary object not only because of its size, but because it may hold clues to one of astronomy’s most persistent mysteries: the existence of intermediate-mass black holes.

Earlier this year, excitement grew when researchers found compelling evidence suggesting that such a black hole might lurk at Omega Centauri’s core. Now, a new study has taken a different approach by searching directly for the black hole’s expected radio signal. The result is striking not because of what was found, but because nothing was detected at all.

Why Omega Centauri Is So Special

Omega Centauri is not an ordinary globular cluster. While most clusters contain a few hundred thousand stars, this one is in a completely different league. Its unusual size, complex stellar populations, and chemical diversity have led many astronomers to believe it is actually the remnant core of a dwarf galaxy that was torn apart and absorbed by the Milky Way billions of years ago.

This idea makes Omega Centauri a prime candidate for hosting a central black hole. If it truly began life as a dwarf galaxy, it may have once possessed a black hole far more massive than those typically found in star clusters.

The Earlier Evidence Pointing to a Black Hole

The renewed interest in Omega Centauri began with a recent Hubble Space Telescope study that analyzed two decades of observations, tracking the motions of 1.4 million stars. Among them, astronomers identified seven stars near the cluster’s core moving at unusually high speeds.

These stars are traveling so fast that, under normal circumstances, they should escape the cluster entirely. Yet they remain gravitationally bound. The most straightforward explanation is that a massive invisible object is exerting a strong gravitational pull on them.

Based on these stellar motions, researchers estimated that the object at the center of Omega Centauri could have a mass of at least 8,200 times that of the Sun, with some models allowing for masses as high as 47,000 solar masses. That range places it squarely in the category of an intermediate-mass black hole, a type that has proven notoriously difficult to confirm.

The Missing Link in Black Hole Evolution

Black holes are usually divided into two well-established groups. Stellar-mass black holes, formed from the collapse of massive stars, typically range from a few to a few hundred solar masses. At the other extreme are supermassive black holes, weighing millions or billions of times more than the Sun and residing at the centers of galaxies.

Intermediate-mass black holes sit between these extremes, and they are critically important for understanding how black holes grow. Many theories suggest that supermassive black holes formed by merging or accreting smaller black holes over cosmic time. If that is true, intermediate-mass black holes should exist in large numbers. Yet confirmed examples remain extremely rare.

Searching for the Black Hole’s Radio Signature

To move beyond indirect evidence, Angiraben Mahida and colleagues set out to search for the black hole itself. When black holes accrete surrounding gas and dust, that material heats up and emits radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, including radio waves.

The team used the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) to observe the central region of Omega Centauri for an impressive 170 hours. These observations were conducted at a frequency of 7.25 gigahertz and reached a sensitivity of 1.1 microjanskys, making this the most sensitive radio image of Omega Centauri ever produced.

If an actively accreting black hole were present, even a relatively quiet one, the telescope should have detected some level of radio emission.

What the Telescopes Found

They found nothing at all.

No radio signal appeared at any of the proposed locations for Omega Centauri’s center, despite careful analysis. The absence of radio emission does not prove that no black hole exists, but it places extremely tight limits on how that black hole must behave.

The study was published on the arXiv preprint server, where it has already attracted attention for its implications.

What a Non-Detection Really Means

Using a well-established relationship known as the fundamental plane of black hole activity, which links black hole mass, radio luminosity, and X-ray luminosity, the researchers calculated how active any central black hole could be.

Their conclusion is that if an intermediate-mass black hole exists in Omega Centauri, its accretion efficiency must be extraordinarily low. The upper limit is about 0.004, meaning less than half a percent of the infalling matter’s rest-mass energy is converted into radiation.

In practical terms, this means the black hole would be almost completely silent, emitting virtually no detectable energy.

A Starved Black Hole in a Cosmic Desert

While this silence might seem surprising, astronomers note that it actually makes sense given Omega Centauri’s environment. Unlike the gas-rich centers of galaxies, globular clusters are typically poor in gas and dust.

If Omega Centauri is indeed the stripped core of a long-destroyed dwarf galaxy, most of its interstellar material would have been lost during the merger with the Milky Way. Without fuel to feed on, even a massive black hole would remain dormant.

This contrasts sharply with supermassive black holes in active galaxies, which are surrounded by abundant material and often shine brightly across the electromagnetic spectrum.

Why This Matters for Astronomy

The results highlight how difficult it is to confirm intermediate-mass black holes using traditional observational methods. Stellar motions can suggest their presence, but electromagnetic signals like radio or X-ray emissions may be absent if the black hole is not actively accreting matter.

This raises broader questions about how many intermediate-mass black holes might exist undetected throughout the universe, quietly influencing their surroundings without announcing themselves through radiation.

The study also underscores the importance of combining multiple observational approaches, from precise stellar dynamics to deep radio and X-ray searches, when investigating these elusive objects.

What Comes Next

Future observations may focus on even deeper radio or X-ray studies, or on refining stellar motion measurements to further narrow down the black hole’s possible mass and location. New instruments and observatories may eventually provide the sensitivity needed to detect faint signals that current telescopes cannot.

For now, Omega Centauri remains a fascinating case where strong gravitational evidence and complete electromagnetic silence coexist, reminding astronomers that the universe does not always behave as expected.

Research Paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.09649