Scientists Are Closing In on Whether TRAPPIST-1 e Has an Atmosphere Using JWST

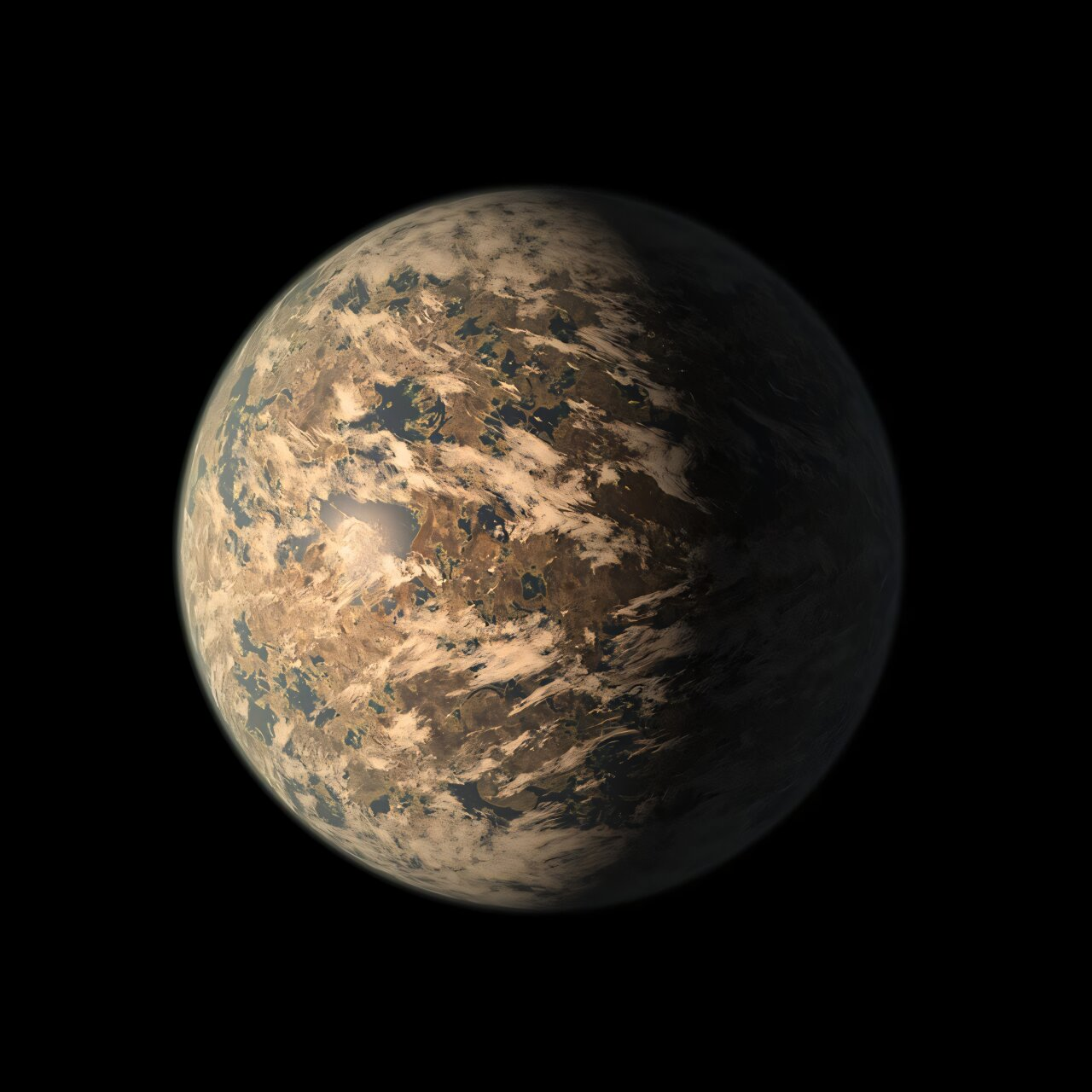

The search for Earth-like worlds beyond our solar system has taken another important step forward, and one of the most closely watched planets remains TRAPPIST-1 e. Located about 40 light-years away, this rocky, Earth-sized exoplanet orbits an ultracool red dwarf star and sits firmly in what astronomers call the habitable zone—the region where liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface. But having the right location is only part of the story. To truly assess habitability, scientists must answer a far tougher question: does TRAPPIST-1 e actually have an atmosphere?

Why TRAPPIST-1 e Matters So Much

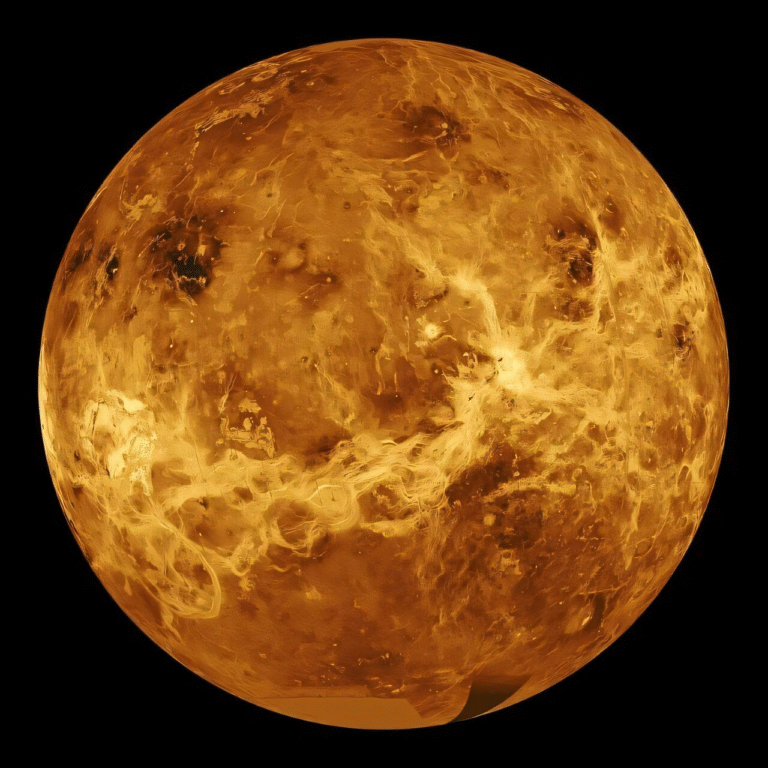

The TRAPPIST-1 system is extraordinary. It contains seven terrestrial planets, all similar in size to Earth, packed into tight orbits around a small, dim red dwarf star. At least four of these planets, including TRAPPIST-1 e, orbit within or near the star’s habitable zone. Because the star is faint and cool, the habitable zone lies very close to it, meaning these planets are likely tidally locked, with one side permanently facing the star and the other in constant darkness.

Among these planets, TRAPPIST-1 e stands out. It has a mass and radius close to Earth’s and receives roughly the same amount of stellar energy. For exoplanet scientists, this makes it one of the best known candidates for a potentially habitable rocky world.

JWST and the Challenge of Detecting Atmospheres

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was designed in part to tackle exactly this kind of problem. One of its major science goals is understanding planetary systems and the origins of life. JWST can analyze exoplanet atmospheres using a technique called infrared transit spectroscopy. When a planet passes in front of its star, a small fraction of starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere. Molecules in that atmosphere absorb specific wavelengths of light, leaving telltale fingerprints in the spectrum.

JWST has already used this method on several exoplanets, including planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system. However, the results so far have revealed a major obstacle: stellar contamination.

The Stellar Contamination Problem Explained

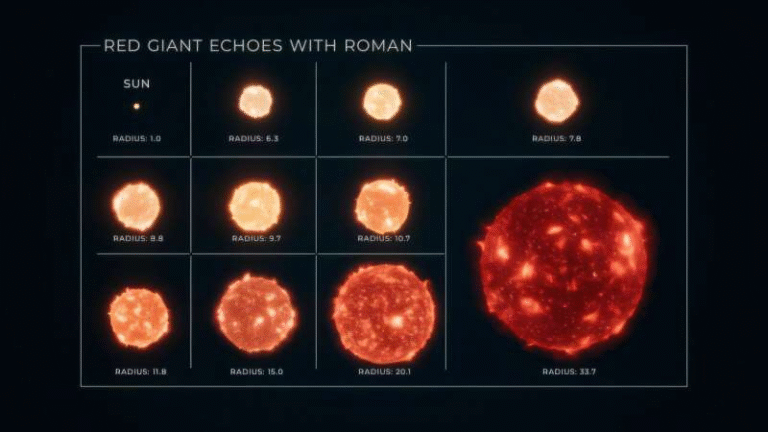

Stars are not smooth, uniform spheres of light. Their surfaces are complex and active. Red dwarf stars like TRAPPIST-1 are especially troublesome because they are magnetically active. Their surfaces are covered with starspots, faculae, and frequent stellar flares.

When a planet transits such a star, it does not block a perfectly even light source. If the planet crosses over a cooler starspot or a hotter region, the resulting signal can mimic or distort atmospheric features. This makes it extremely difficult to separate what belongs to the planet’s atmosphere from what originates on the star itself.

JWST’s incredible sensitivity makes this problem even more pronounced. Subtle stellar effects that older telescopes might have missed now stand out clearly, complicating interpretation.

Lessons From Other Exoplanets

This is not the first time astronomers have encountered this issue. In 2023, JWST observed GJ 486 b, a rocky exoplanet orbiting another red dwarf star. Scientists detected water vapor, a potentially exciting finding, but could not determine with certainty whether the signal came from the planet’s atmosphere or from water-related features on the star’s surface. This ambiguity highlighted how serious stellar contamination can be.

A New Strategy Using TRAPPIST-1 b

To tackle this problem for TRAPPIST-1 e, researchers launched a new observational effort known as the JWST TRAPPIST-1 e/b Program. The study is led by Natalie Allen, a Ph.D. student at Johns Hopkins University, and will be published in The Astronomical Journal. A preprint is already available on arXiv.

The key idea behind the program is clever and practical. Another planet in the same system, TRAPPIST-1 b, is believed to be airless. JWST observations strongly suggest that this planet lacks a significant atmosphere. Because of this, its transit signal mainly reflects stellar contamination alone, without any atmospheric contribution.

By observing close transits—situations where TRAPPIST-1 b and TRAPPIST-1 e transit the star within eight hours of each other—scientists can use TRAPPIST-1 b as a baseline. Since eight hours is only about 10 percent of the star’s 3.3-day rotation period, the stellar surface should not change dramatically between the two transits. In theory, subtracting the TRAPPIST-1 b signal from TRAPPIST-1 e’s data should remove much of the stellar noise.

Early Results and Persistent Challenges

The paper presents only the first observations from what will be a multi-cycle JWST program. Earlier JWST data showed that stellar contamination in the TRAPPIST-1 system is extreme, and these new observations confirm just how difficult the problem is.

One major complication is stellar flaring. In the new data, flares appear in every observation, clearly visible in H-alpha measurements, which are commonly used to track stellar activity. In one case, a flare occurred just before the end of TRAPPIST-1 e’s transit. These flares undermine a core assumption of the close-transit method: that the stellar surface remains stable between the two planetary transits.

Despite this, the researchers remain cautiously optimistic. They propose observing 15 close transit pairs, which should provide enough data to statistically overcome these variations.

The Importance of Carbon Dioxide

The team’s simulations suggest that this approach could detect an Earth-like atmosphere on TRAPPIST-1 e with strong statistical confidence—but only if a specific molecular signature is present. That signature is the 4.3-micron carbon dioxide (CO₂) absorption feature.

This particular CO₂ feature is one of the strongest and most isolated absorption bands in infrared spectra. Because it is relatively free from overlapping signals, it is less likely to be confused with stellar contamination. The presence of CO₂ would also be consistent with a secondary atmosphere, one formed through volcanic outgassing or other geological processes rather than being primordial hydrogen gas.

Secondary atmospheres are especially interesting because they can, in some cases, be linked to biological or geochemical activity.

Why This Matters Beyond TRAPPIST-1

While this study focuses on TRAPPIST-1 e, the implications are much broader. Stellar contamination affects all attempts to study rocky exoplanet atmospheres, not just those around red dwarfs. Even Sun-like stars have surface activity that can interfere with precise measurements.

So far, astronomers have no conclusive detection of an atmosphere on a rocky, Earth-sized exoplanet. Solving the stellar contamination problem is a critical step toward changing that.

Looking Ahead

The early results suggest that the close-transit technique has real potential, even if it faces significant hurdles. If successful, it could finally allow scientists to determine whether TRAPPIST-1 e has an atmosphere—and what that atmosphere is made of.

That answer would not only deepen our understanding of one remarkable planet but also bring us closer to answering one of astronomy’s biggest questions: how common are truly Earth-like worlds in our galaxy?

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.07695