Scientists Discover a Single Chemical Bond That Helps Viruses Infect Hosts Faster

Viruses are often described as nature’s perfect geometric machines—tiny, symmetrical shells built with mathematical precision to protect and deliver genetic material. But new research from Pennsylvania State University challenges that long-held idea. Scientists have uncovered that some viruses intentionally build small structural imperfections into their shells, and these imperfections play a crucial role in how quickly and efficiently infections begin.

At the center of this discovery is a single chemical bond that subtly breaks symmetry inside a virus. This bond creates direction, speed, and efficiency during infection, helping the virus release its genetic material at exactly the right place inside a host cell. The findings were published in Science Advances, and the researchers have also filed a patent application based on the work.

Viruses Are Not as Perfectly Symmetrical as We Thought

For decades, viruses have been modeled as highly symmetrical structures. Many viruses, including those that infect humans, form shells known as icosahedral capsids, which have 20 identical triangular faces. This symmetry was assumed to be essential for stability and efficient assembly.

However, the Penn State research team discovered that at least some viruses intentionally disrupt this symmetry. Instead of being a flaw, this imbalance turns out to be a functional advantage.

The team focused on the Turnip Crinkle Virus (TCV), a plant virus that infects crops and serves as an excellent model for studying viral structure. TCV has the same general shell shape as many human pathogens, including poliovirus, norovirus, enteroviruses, hepatitis B virus, and the virus that causes chickenpox. That makes the findings especially relevant beyond plant biology.

The Isopeptide Bond That Changes Everything

The key discovery is a single isopeptide bond inside the viral shell. An isopeptide bond is a strong chemical link formed between specific amino acids in proteins. In this case, the bond connects two structural proteins that make up the virus’s protective shell.

That one bond is enough to tip the balance inside the virus. It creates a subtle asymmetry, pulling the viral RNA toward one side of the particle instead of letting it float evenly throughout the interior.

This asymmetry gives the virus what researchers describe as polarity, meaning it now has a functional “direction.” Instead of being uniform in all orientations, the virus is biased toward releasing its genetic material from one specific location.

A “Loaded Die” Inside the Virus

To explain this mechanism, the researchers used a simple analogy: a loaded die. Just like a weighted die is more likely to land on a certain number, the virus’s internal imbalance ensures that its RNA exits through a preferred point.

When the virus enters a host cell and begins to break apart, the RNA does not drift randomly. Instead, it is already positioned near a specific exit site. The isopeptide bond acts like a molecular strap or hinge, anchoring the RNA and keeping it slightly off-center.

As the viral shell loosens, this creates a spring-loaded effect. The RNA is rapidly ejected in a single direction, rather than slowly leaking out. This speed gives the virus a major advantage during the earliest moments of infection.

Why Speed and Direction Matter During Infection

Once inside a host cell, timing is everything. The faster a virus can release its genetic material, the better its chances of taking control before the host mounts a defense.

In the case of Turnip Crinkle Virus, the RNA is released close to the host’s ribosomes, which are the cell’s protein-making machines. This positioning allows the virus to immediately begin producing viral proteins without delay.

Instead of floating around the cell and risking degradation or detection, the RNA is delivered exactly where it needs to be. This precision helps explain why even simple viruses can be remarkably efficient at infecting hosts.

Advanced Imaging Reveals the Hidden Mechanism

Capturing this process required cutting-edge technology. The research team used two advanced imaging methods:

- Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which allows scientists to visualize biological structures at near-atomic resolution while they are frozen in action

- Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry, which tracks subtle changes in protein flexibility and interactions

Using these tools, the researchers were able to observe a partially expanded virus that was poised to release its RNA. This intermediate state had never been clearly visualized before.

The images showed that the viral particle had a clear internal polarity and that the RNA was clustered near the same region where the shell appeared ready to open.

A Potential Universal Strategy Among Viruses

Although this study focused on a plant virus, the implications go far beyond agriculture. Many viruses that infect humans share the same icosahedral shell structure as Turnip Crinkle Virus.

This suggests that the “loaded die” mechanism may be a widespread strategy used by viruses to control genome release. If similar asymmetric bonds exist in human viruses, they could explain how these pathogens achieve such rapid and precise infections.

Understanding this mechanism adds a new layer to how scientists think about viral assembly and disassembly—processes that were once believed to be driven almost entirely by symmetry.

Implications for Antiviral Drugs

The discovery opens promising new avenues for antiviral drug development. If viruses rely on specific asymmetric features to maintain their spring-loaded state, disrupting those features could slow or stop infection.

Drugs could potentially be designed to bind near the isopeptide link or other asymmetric sites, destabilizing the viral shell. Without proper asymmetry, the virus may struggle to release its RNA efficiently, making it less infectious and easier for the immune system to control.

This approach could complement existing antiviral strategies, especially for viruses that rapidly evolve resistance to traditional drugs.

New Opportunities for Vaccines and RNA Therapies

Beyond antivirals, the findings have exciting implications for vaccines and RNA-based therapeutics. Many modern vaccines and treatments rely on delivering RNA into cells, but ensuring that RNA reaches the right location remains a challenge.

By learning from viruses that have perfected this process, scientists may be able to design delivery systems that release RNA closer to protein-making machinery, improving stability and effectiveness.

The research team is already exploring whether this naturally occurring mechanism can be used to amplify expression of therapeutic RNAs, particularly in plant virus vectors that are cost-efficient and scalable.

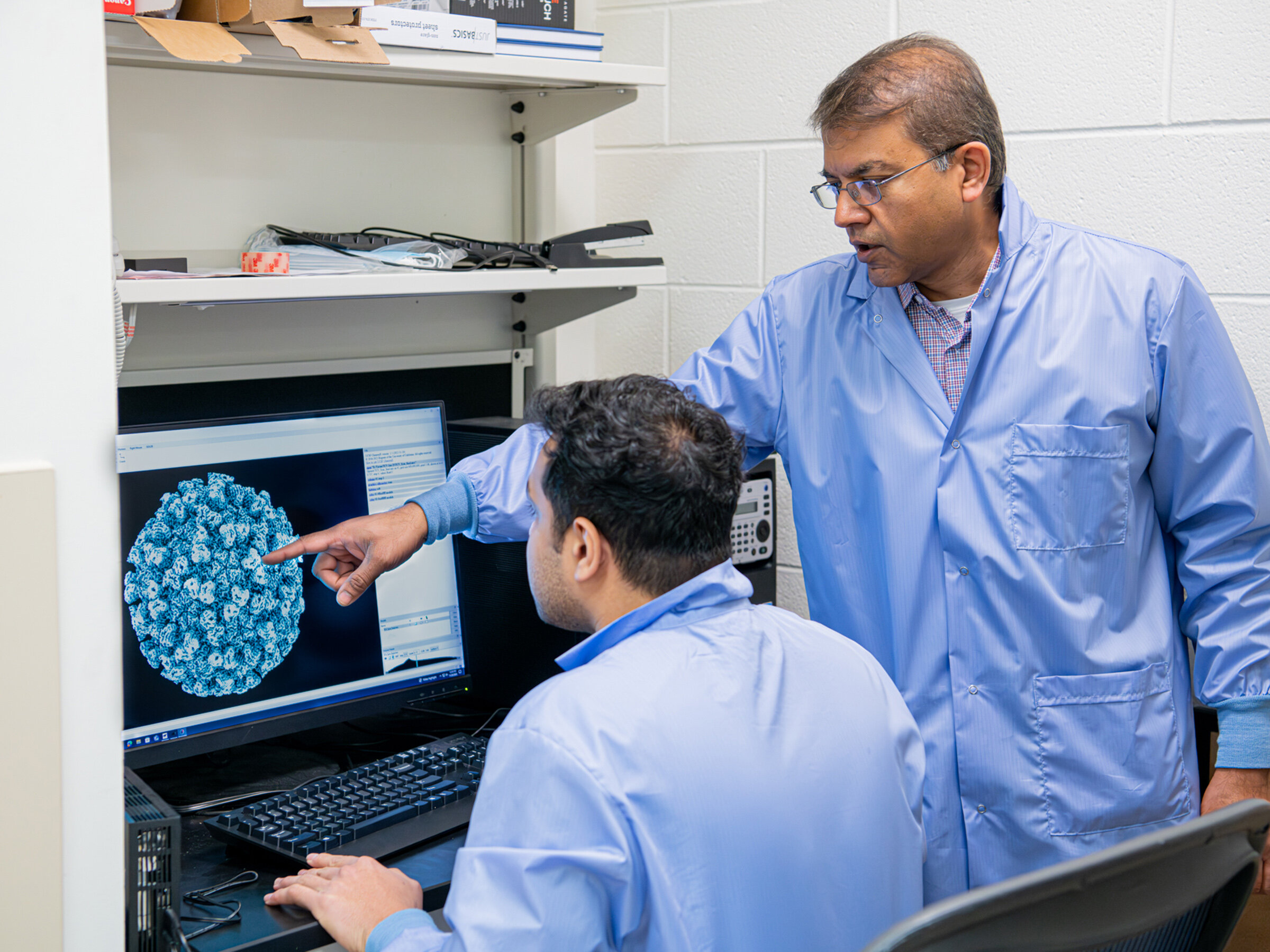

Who Conducted the Study

The research was led by Ganesh Anand, associate professor of chemistry, biochemistry, and molecular biology at Penn State. Key contributors include Varun Venkatakrishnan, who led the cryo-EM work, and Sean Braet, a postdoctoral researcher involved in imaging and therapeutic implications.

Additional contributors include undergraduate researcher Molly Clawson, proteomics expert Tatiana Laremore, and collaborators Ranita Ramesh and Sek-Man Wong from the National University of Singapore.

Why This Discovery Matters

This study reshapes how scientists understand viruses at a fundamental level. Rather than being perfectly symmetrical machines, viruses can be strategically imperfect, using tiny molecular features to gain speed, precision, and efficiency.

By uncovering how a single chemical bond can influence infection speed, researchers have opened the door to new ways of fighting viruses—and even borrowing their tricks for medical innovation.

Research paper: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ady4104