New Roundworm Species Found in the Great Salt Lake Reveals Hidden Life in an Extreme Ecosystem

Scientists studying Utah’s Great Salt Lake have uncovered a surprising new resident living beneath its highly saline waters: a microscopic roundworm species completely new to science, and possibly a second one still under investigation. This discovery adds an unexpected layer of complexity to one of North America’s most extreme and ecologically important lakes, while also raising fascinating questions about evolution, survival, and ecosystem health.

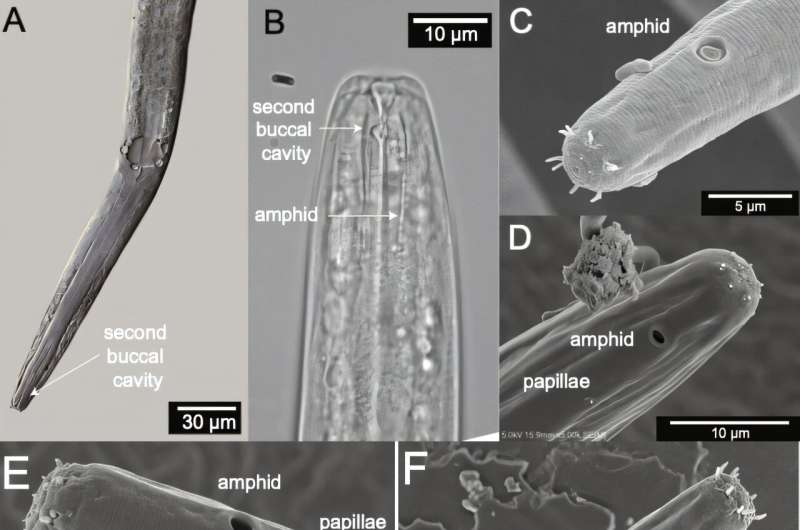

The research, led by a team from the University of Utah, was published in the Journal of Nematology and formally describes a new nematode species named Diplolaimelloides woaabi. The species name honors the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, whose ancestral lands include the Great Salt Lake. Tribal elders recommended the word Wo’aabi, meaning “worm,” reflecting a collaborative approach between scientists and Indigenous communities.

A Tiny Creature With Big Scientific Importance

Nematodes, commonly known as roundworms, are among the most widespread animals on Earth. They are found in nearly every environment imaginable, from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to polar ice and ordinary garden soil. Most are less than a millimeter long, which explains why they often go unnoticed. Despite their size, nematodes are extraordinarily abundant, making up around 80% of all animal life in terrestrial soils and about 90% on the ocean floor.

Given their ubiquity, it may seem surprising that no nematodes had been positively identified in the Great Salt Lake until 2022. That changed when field expeditions led by Julie Jung, then a postdoctoral researcher in Michael Werner’s lab, recovered nematodes from the lake’s microbialites. Microbialites are rock-like structures formed by communities of microorganisms, and they cover parts of the lakebed.

The team suspected early on that the worms might represent a new species, but confirming that required three additional years of detailed genetic and taxonomic analysis. Those efforts have now paid off, resulting in the formal description of Diplolaimelloides woaabi.

Only the Third Animal Group Known in the Lake

The Great Salt Lake is famous for its extreme salinity, which makes survival difficult for most animals. Until now, only two types of animals were known to inhabit its waters: brine shrimp and brine flies. These species are vital because they support massive populations of migratory birds that rely on the lake as a feeding stopover.

With this discovery, nematodes become just the third metazoan group confirmed to live in the lake. That alone makes the finding significant, but there may be more to come. Genetic evidence collected by the research team suggests there are at least two distinct nematode populations in the Great Salt Lake. One of them has been formally described as Diplolaimelloides woaabi, while the second may represent another new species, pending further research.

A Worm Built for Extreme Conditions

Based on genetic and anatomical evidence, the newly identified species belongs to the family Monhysteridae, an ancient group of nematodes known for their ability to thrive in extreme environments, including highly saline habitats. More specifically, the worm is part of the genus Diplolaimelloides, which typically includes free-living nematodes found in coastal marine and brackish environments.

What makes this discovery particularly intriguing is geography. Diplolaimelloides woaabi is now one of only two known members of this genus that do not live near the ocean, the other being found in eastern Mongolia. The Great Salt Lake sits about 4,200 feet above sea level and roughly 800 miles from the nearest coastline, raising an obvious question: how did this worm get there?

Two Competing Theories About Its Origins

Scientists are currently considering two main explanations, both unusual in their own way.

The first theory suggests that the nematodes may be ancient survivors, dating back tens of millions of years. During the Cretaceous Period, much of what is now Utah was located along the western edge of a massive inland sea that split North America. As geological uplift formed the Colorado Plateau and the Great Basin, populations of marine organisms could have become isolated, eventually adapting to inland environments.

However, the region’s history complicates this idea. Between 20,000 and 30,000 years ago, northern Utah was covered by Lake Bonneville, a massive freshwater lake. If the nematodes have been present since ancient times, they would have had to survive dramatic shifts from marine to freshwater and then to hypersaline conditions, potentially multiple times.

The second theory is even more surprising. It proposes that nematodes may have been transported to the Great Salt Lake by migratory birds, possibly hitching a ride on feathers or feet after contact with saline lakes elsewhere, including South America. While this idea may sound far-fetched, long-distance dispersal by birds is known to occur for some small organisms.

At this stage, researchers do not know which explanation is correct, and future studies will be needed to test both possibilities.

Strange Findings in the Lab

Once the nematodes were brought into the laboratory, researchers noticed another puzzle. In samples collected directly from the lake, females made up more than 99% of the population. Yet when the worms were cultured in laboratory conditions, the sex ratio shifted dramatically, with males accounting for about 50%.

This discrepancy suggests that something about the lake’s natural environment strongly influences reproduction or survival, though exactly what that factor is remains unclear.

The worms were found living primarily in the top few centimeters of algal mats on the microbialites, where they feed on bacteria. Below that shallow layer, the nematodes were not detected at all, indicating a very specific ecological niche.

Why This Discovery Matters

Although tiny, nematodes play outsized roles in ecosystems. They are essential to nutrient cycling, microbial regulation, and food webs in many environments. Importantly, nematodes are also widely used as bioindicators, meaning their presence, abundance, and diversity can reveal changes in environmental conditions such as salinity, pollution, and sediment chemistry.

The Great Salt Lake is under significant human pressure, including water diversion, climate-driven drought, and increasing salinity. Because only a handful of species can survive such extreme conditions, those species tend to be especially sensitive to change. This makes Diplolaimelloides woaabi a potential early warning system for detecting ecological stress in the lake.

The fact that the species appears confined to microbialites is also notable. Microbialites are crucial to the lake’s productivity, forming the base of much of its food web. Any interaction between nematodes and microbial communities could have ripple effects throughout the entire ecosystem.

Learning More About Nematodes Beyond the Lake

Outside the Great Salt Lake, nematodes are already known to be among the most diverse and adaptable animals on the planet, with more than 250,000 species estimated, though only a fraction have been formally described. Many play beneficial roles, while others are agricultural pests or parasites. Studying extremophile species like Diplolaimelloides woaabi helps scientists understand how life adapts to harsh environments, knowledge that can inform fields ranging from ecology to evolutionary biology.

Research Reference

Journal of Nematology: Diplolaimelloides woaabi sp. n. (Nematoda: Monhysteridae): A Novel Species of Free-Living Nematode from the Great Salt Lake, Utah

https://doi.org/10.2478/jofnem-2025-0048