Engineered Bacteria Could Make Tagatose the Most Practical Healthier Sugar Substitute Yet

For more than a century, scientists and food manufacturers have been searching for a way to enjoy sweetness without the well-known downsides of sugar. From early artificial sweeteners like saccharin to plant-derived options such as stevia and monk fruit, each alternative has come with trade-offs—whether it’s taste, texture, cost, or health concerns. Now, researchers from Tufts University have taken a major step toward solving this problem by developing a new bacterial method to produce tagatose, a rare sugar that tastes remarkably like table sugar but behaves very differently in the body.

This breakthrough, published in Cell Reports Physical Science in 2025, outlines how genetically engineered bacteria can convert ordinary glucose into tagatose with extremely high efficiency. The approach could make tagatose cheaper, more scalable, and far more practical for everyday food products than ever before.

What Is Tagatose and Why Is It So Interesting?

Tagatose is classified as a rare sugar, meaning it exists naturally but only in very small quantities. Chemically, it is similar to fructose, but its metabolic effects are quite different. Tagatose delivers about 92% of the sweetness of sucrose, yet it contains roughly 60% fewer calories.

In nature, tagatose appears in trace amounts when lactose breaks down, such as during the heating or enzymatic processing of dairy products like yogurt, cheese, and kefir. Small quantities are also found in fruits including apples, pineapples, and oranges. However, in these sources, tagatose typically makes up less than 0.2% of total sugars, making direct extraction impractical.

Because of this scarcity, tagatose has traditionally been manufactured rather than harvested. Existing production methods work, but they tend to be expensive, inefficient, and limited in scale, which has prevented tagatose from becoming a mainstream sugar replacement.

The Problem With Traditional Tagatose Production

Earlier manufacturing processes usually start with galactose, a sugar derived from lactose. Galactose itself is less abundant and more costly than glucose, which immediately drives up production costs. On top of that, conventional chemical or enzymatic conversion processes often result in low to moderate yields, typically ranging from 40% to 77%.

These limitations have kept tagatose confined to niche uses, despite its appealing nutritional profile and favorable taste. The Tufts research team set out to change that by rethinking how tagatose could be made from the ground up.

Turning E. coli Into Tiny Sugar Factories

The new approach centers on engineering Escherichia coli bacteria to perform a carefully designed sequence of biochemical reactions. Instead of starting with galactose, the bacteria are fed glucose, one of the most abundant and inexpensive sugars available.

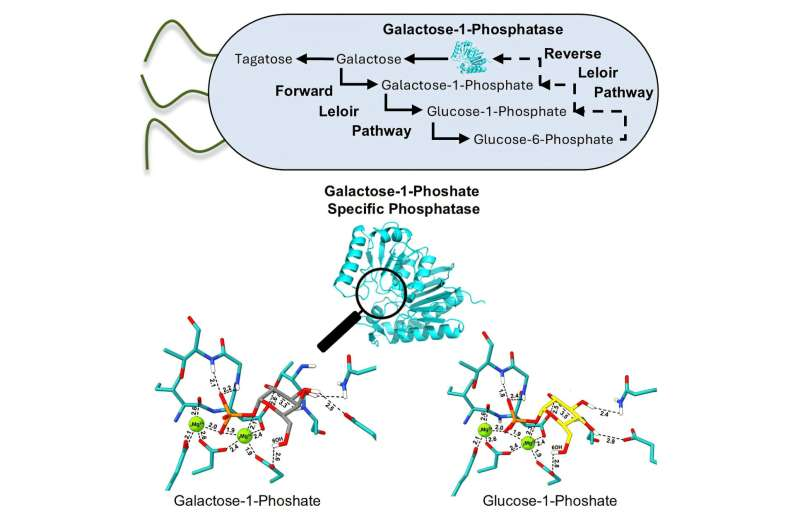

The key innovation lies in reprogramming a natural metabolic route known as the Leloir pathway. Under normal circumstances, this pathway helps organisms convert galactose into glucose for energy. The researchers effectively reversed this pathway, allowing glucose to be transformed into galactose instead.

This reversal was made possible by introducing a newly discovered enzyme from slime mold, known as galactose-1-phosphate-selective phosphatase, or Gal1P. Once galactose is produced inside the bacterial cell, a second enzyme—arabinose isomerase—converts it into tagatose.

By combining these enzymes inside a single bacterial system, the researchers created a highly efficient, self-contained production process.

Exceptionally High Yields From a Simple Sugar

One of the most striking outcomes of this work is the yield. The engineered bacteria were able to convert glucose into tagatose with yields reaching up to 95%, far surpassing conventional manufacturing methods.

Using glucose as a feedstock also dramatically improves economic feasibility. Glucose is cheap, widely available, and already used at industrial scale in fermentation-based processes. This means the method could potentially be integrated into existing food biotechnology infrastructure with fewer barriers.

Health Benefits That Go Beyond Fewer Calories

Tagatose stands out not just because it is lower in calories, but because of how the body processes it. Unlike sucrose, tagatose is only partially absorbed in the small intestine. A significant portion passes into the colon, where it is fermented by gut bacteria.

As a result, tagatose has a minimal impact on blood glucose and insulin levels, making it especially attractive for people with diabetes or insulin resistance. Clinical studies have shown very small increases in plasma glucose and insulin following tagatose consumption.

There are also promising signs for dental health. While sucrose feeds cavity-causing bacteria in the mouth, tagatose appears to inhibit the growth of some of these bacteria, potentially reducing the risk of tooth decay. Evidence also suggests tagatose may support beneficial gut and oral microbes, giving it mild probiotic-like properties.

Importantly, tagatose has already been designated Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, placing it in the same safety category as everyday ingredients like salt and vinegar.

Why Tagatose Works in Real Food, Not Just the Lab

Many sugar substitutes fail when it comes to real-world cooking and baking. High-intensity sweeteners often provide sweetness without bulk, leading to disappointing textures and poor browning.

Tagatose, however, is considered a bulk sweetener, meaning it behaves much like sugar in recipes. It adds volume, contributes to mouthfeel, and browns during cooking, making it suitable for baked goods and other applications where sugar plays a structural role.

Taste testing has also shown that tagatose is one of the closest matches to table sugar among alternative sweeteners, avoiding the bitter or metallic aftertastes that turn many consumers away from substitutes.

Broader Implications for Food and Sustainability

This research does more than improve one sweetener. It demonstrates how metabolic engineering can unlock the production of rare sugars and other valuable compounds from inexpensive raw materials. By reversing and redesigning biological pathways, scientists can create more sustainable and efficient food ingredients.

If scaled successfully, fermentation-based tagatose production could reduce reliance on traditional sugar while lowering environmental impact compared to chemical synthesis methods.

What Comes Next?

While the study represents a major step forward, additional work is needed before tagatose becomes commonplace. Future efforts will likely focus on industrial-scale optimization, regulatory approval for manufacturing processes, and partnerships with food producers.

Still, the combination of high yield, low cost, favorable taste, and strong health profile makes tagatose one of the most promising sugar alternatives developed so far.

Research paper:

https://www.cell.com/cell-reports-physical-science/fulltext/S2666-3864(25)00592-2