A New One-Two Drug Strategy Shows Promise Against Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, often shortened to TB, is one of those diseases many people assume belongs to the past. Unfortunately, that’s far from true. Even today, TB kills more people globally than any other infectious disease, despite being both preventable and curable. One of the biggest reasons it continues to claim lives is the steady rise of drug-resistant tuberculosis, which makes standard treatments less effective and far more complicated.

Now, a new study from researchers at Rockefeller University, published in Nature Microbiology, offers an encouraging new way forward. Instead of trying to replace existing TB drugs, the researchers show how pairing an old, trusted antibiotic with a carefully chosen second compound can dramatically improve outcomes. The approach is precise, science-driven, and surprisingly elegant in how it turns bacterial resistance into a weakness.

Why Rifampicin Alone Is No Longer Enough

For decades, rifampicin has been a cornerstone of TB treatment. The drug works by blocking a critical bacterial enzyme called RNA polymerase, which TB bacteria need to copy their DNA into RNA and survive. Rifampicin is powerful, reliable, and even capable of killing some of the slow-growing or dormant TB bacteria that hide deep in lung tissue.

But there’s a problem. TB bacteria have been evolving. A growing number of strains have developed resistance to rifampicin, often due to a specific mutation in RNA polymerase known as βS450L. Once this mutation appears, rifampicin becomes far less effective, and treatment options shrink dramatically.

Traditionally, the solution to drug resistance has been to search for entirely new antibiotics. This study takes a different path. Instead of abandoning rifampicin, the researchers asked a more interesting question: what if resistance itself creates a vulnerability that can be exploited?

Targeting Transcription From Two Directions

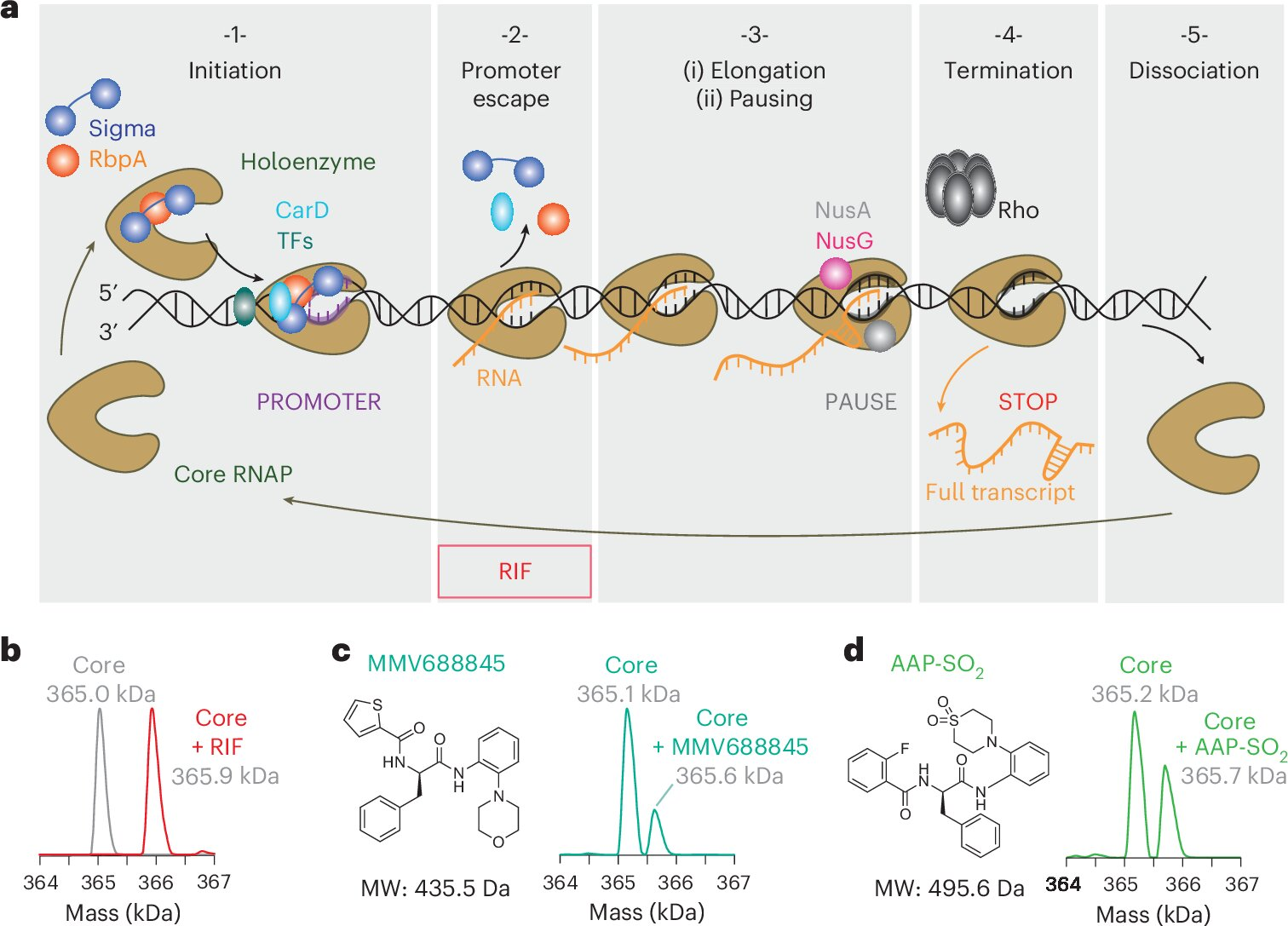

To understand the new strategy, it helps to know how bacterial transcription works. Transcription isn’t a single action. It happens in stages. First, RNA polymerase starts transcription and escapes the promoter region of DNA. Then comes elongation, where RNA polymerase steadily copies the genetic code. Rifampicin mainly blocks that first step.

Previous research from the same labs showed something intriguing. The βS450L resistance mutation allows TB bacteria to dodge rifampicin, but it also slows down the elongation phase of transcription. That slowdown makes the transcription process more error-prone and prone to stalling.

The researchers realized this weakness might be the key.

They paired rifampicin with a second compound called AAP-SO₂, which specifically targets the elongation stage of transcription. This approach, known as vertical inhibition, blocks two steps of the same essential pathway rather than attacking unrelated bacterial systems.

What Is AAP-SO₂ and Why It Matters

AAP-SO₂ is not a finished drug or something ready for clinical use. Instead, it’s best described as a proof-of-concept compound. Its role in the study was to test whether slowing transcription elongation could enhance rifampicin’s effects.

Detailed experiments confirmed that AAP-SO₂ binds directly to bacterial RNA polymerase at a different site than rifampicin. That distinction is critical. Because the two compounds don’t compete for the same binding location, they can work together at the same time.

On its own, AAP-SO₂ slows down transcription. When combined with rifampicin, the effect becomes much more powerful, especially against rifampicin-resistant TB strains.

Turning Resistance Into a Disadvantage

One of the most striking findings of the study is how the drug combination affects rifampicin-resistant bacteria. The βS450L mutation helps TB survive rifampicin, but it also makes RNA polymerase sluggish. AAP-SO₂ takes advantage of that slowdown.

In laboratory cultures, AAP-SO₂ was able to wipe out rifampicin-resistant bacteria, effectively removing that resistant mutation from the population. Once the mutation disappeared, the bacteria once again became vulnerable to rifampicin.

This means the combination doesn’t just kill bacteria more effectively. It also slows the emergence of resistance, which is one of the biggest challenges in TB treatment worldwide.

Why Granulomas Are So Important

TB bacteria don’t just float freely in the body. They often hide inside dense clusters of immune cells in the lungs called granulomas. Inside these structures, bacteria can enter a dormant or slow-growing state, making them extremely difficult to kill with standard antibiotics.

To test whether their strategy would work in a more realistic environment, the researchers used a rabbit model designed to mimic human TB granulomas. This is where the results became especially impressive.

In simple liquid cultures, rifampicin and AAP-SO₂ worked additively. Each drug contributed its own effect, but neither boosted the other dramatically. Inside granuloma-like tissue, however, the combination became synergistic. Together, the drugs killed far more bacteria than either one could alone.

The researchers estimate that AAP-SO₂ increased the effective potency of rifampicin by about 30-fold in these conditions. That kind of boost could make a meaningful difference in real-world treatment, especially for stubborn infections that linger for months.

Reinforcing Old Drugs Instead of Replacing Them

An important takeaway from this study is that rifampicin is not being replaced. Instead, it’s being reinforced. Rifampicin remains one of the most valuable TB drugs ever developed, and this research shows it can be made even more effective with the right companion compound.

Although AAP-SO₂ itself is not suitable as a medication, the research team has already filed a provisional patent covering the dual-inhibition strategy. The next step is to develop safer, more stable derivatives that could eventually be tested in humans.

A Shift Toward Precision Medicine for TB

Beyond any single compound, this research points toward a broader shift in how TB drugs might be developed. Instead of treating all TB infections the same way, future therapies could be tailored to the specific resistance mutations present in a patient’s strain.

This precision medicine approach reframes resistance mutations not just as obstacles, but as clues. By understanding exactly how a mutation changes bacterial behavior, scientists can design drug combinations that exploit those changes rather than fighting against them blindly.

Why This Matters in the Bigger Picture

Drug-resistant TB, including multidrug-resistant (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR-TB) forms, remains one of the most serious public health threats globally. Treatments are long, expensive, and often difficult for patients to complete. Any strategy that can shorten treatment, reduce resistance, or improve drug effectiveness could save countless lives.

This study shows how basic molecular biology can directly guide smarter therapeutic strategies. By deeply understanding how TB bacteria transcribe their genes and how resistance alters that process, researchers are finding new ways to stay one step ahead.

The work doesn’t offer an immediate cure, but it provides a clear, evidence-based path toward better TB treatments built on knowledge rather than guesswork.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-025-02201-6