Scientists Discover a Non-Coding Gene That Directly Controls Cell Size

Scientists have finally answered a long-standing biological question: what keeps our cells the right size? For decades, researchers knew that cell size matters—cells that grow too large or remain too small are linked to conditions such as cancer, anemia, and neurological disorders—but the exact genetic control behind cell size remained unclear. Now, a new study has revealed something groundbreaking. For the first time, scientists have identified a non-coding gene that directly regulates how big or small our cells become.

This discovery comes from a research team at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) and was published in the journal Nature Communications. The gene, known as CISTR-ACT, does not produce a protein. Instead, it belongs to a class of genetic material called long non-coding RNA, or lncRNA, and it plays a central role in controlling cell growth across multiple cell types and even across species.

Why Cell Size Is Such a Big Deal

Cell size might sound like a minor detail, but it is a fundamental feature of life. Every cell type in the body—red blood cells, brain cells, bone marrow cells—has an optimal size that allows it to function properly. When cells deviate from this range, serious problems can arise. Oversized red blood cells are linked to certain forms of anemia, while abnormal cell growth is a hallmark of cancer.

Until now, most known regulators of cell size were protein-coding genes involved in metabolism, growth signals, or cell division. What scientists lacked was a direct genetic switch that could independently set cell size. The discovery of CISTR-ACT fills this gap and changes how researchers think about cell biology.

What Makes CISTR-ACT So Unique

CISTR-ACT is part of the non-coding genome, which makes up roughly 98 percent of human DNA. These regions do not produce proteins, and for many years they were dismissed as “junk DNA.” Over the past two decades, that view has shifted dramatically as scientists uncovered regulatory roles for non-coding regions. Still, finding a non-coding gene that directly controls cell size is unprecedented.

CISTR-ACT produces a long non-coding RNA molecule that acts as a regulatory signal inside the cell. Unlike proteins, lncRNAs often work by interacting with DNA, RNA, or proteins to influence how other genes are switched on or off. In this case, CISTR-ACT acts as a master regulator of cell size, operating through multiple biological pathways.

How Scientists Identified the Gene

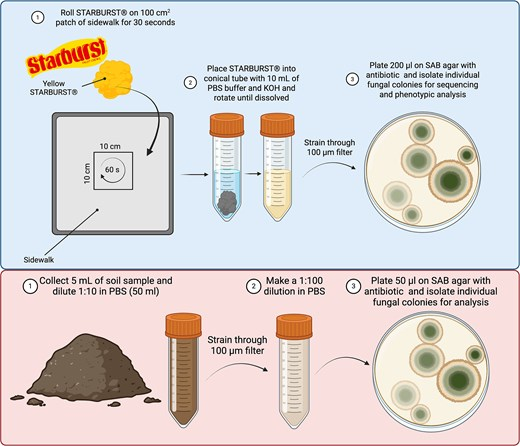

The research team used a combination of advanced gene-editing tools and computational analysis. They employed CRISPR/Cas9, which edits DNA, and Cas13, which targets RNA, allowing them to precisely manipulate both the gene itself and the RNA it produces.

By reducing or completely removing CISTR-ACT in preclinical models, the scientists observed consistently larger cells, including oversized red blood cells. In brain tissue, changes in cell size were accompanied by alterations in brain structure. These effects closely mirrored what has been observed in human disease conditions linked to abnormal cell size.

When the researchers increased the amount of CISTR-ACT instead, the results flipped: cells became smaller. This clear cause-and-effect relationship confirmed that CISTR-ACT is not just associated with cell size—it actively controls it.

A Dual Role at the DNA and RNA Levels

One of the most striking findings of the study is that CISTR-ACT works at two different biological levels.

At the DNA level, the location of the CISTR-ACT gene helps organize nearby genes involved in cell growth, structure, and adhesion. Its presence influences how these neighboring genes are regulated as a group.

At the RNA level, the lncRNA produced by CISTR-ACT acts as a guide for a protein called FOSL2. FOSL2 is a transcription factor, meaning it binds to DNA to control the activity of other genes. CISTR-ACT essentially directs FOSL2 to the correct genetic targets. Without CISTR-ACT, FOSL2 fails to bind properly, disrupting the regulation of thousands of genes related to cell size and structure.

This dual mechanism makes CISTR-ACT especially powerful and explains why its effects are so consistent across different tissues.

Effects Across Cell Types and Species

Another key aspect of this discovery is that the function of CISTR-ACT is highly conserved. The researchers observed similar effects in human cells and mouse models, suggesting that this regulatory mechanism evolved early and has been maintained throughout evolution.

The gene plays a particularly important role in brain development and bone marrow, where precise control of cell size is essential. In bone marrow, where red blood cells are produced, disruptions in cell size can directly affect oxygen transport. In the brain, even small changes in cell size can alter neural circuits and brain structure.

Links to Disease and Medical Potential

CISTR-ACT was not completely unknown before this study. Previous work had linked it to Mendelian diseases and cartilage malformations, but its broader biological role remained unclear. This new research connects those observations to a fundamental cellular mechanism.

Because abnormal cell size is a feature of many diseases, the discovery of CISTR-ACT opens new avenues for precision medicine. Conditions such as cancer, where cells often grow uncontrollably, or anemia, where red blood cell size is disrupted, could one day be treated by targeting non-coding RNAs like CISTR-ACT.

While clinical applications are still far in the future, the findings suggest that non-coding RNAs may become drug targets, an area that is only beginning to be explored.

Understanding Long Non-Coding RNAs

Long non-coding RNAs are typically more than 200 nucleotides long and do not encode proteins. Instead, they influence gene expression by shaping chromatin structure, guiding proteins, or interacting with other RNA molecules. Thousands of lncRNAs exist in the human genome, but only a small fraction have been well studied.

The discovery of CISTR-ACT provides strong evidence that lncRNAs can have direct, measurable effects on core cellular properties, not just subtle regulatory roles. This finding is likely to accelerate research into other non-coding RNAs that may control different aspects of cell behavior.

What Comes Next

The researchers emphasize that more work is needed to fully understand how CISTR-ACT guides FOSL2 and whether similar mechanisms exist in other cell types. Future studies will likely explore whether additional non-coding genes control other physical traits of cells, such as shape, stiffness, or lifespan.

What is already clear is that this discovery reshapes how scientists think about genetics. The non-coding genome is no longer a passive backdrop—it is an active controller of essential biological functions, including something as fundamental as cell size.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67591-x