Ancient Bees Once Built Their Nests Inside Owl-Leftover Bones, Scientists Discover

Around 20,000 years ago, long before humans documented ecosystems or cataloged insect behavior, a quiet and unexpected interaction was unfolding inside a limestone cave on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. Owls were living, hunting, and regurgitating pellets full of bones. Much later, ancient bees found those very bones to be the perfect place to raise their young.

This unusual discovery, documented in a 2025 study published in Royal Society Open Science, marks the first known evidence of bees using animal bones as nesting sites. It sheds light not only on the adaptability of bees, but also on how seemingly unrelated animals can shape ecosystems in surprising ways.

A Cave Filled With Clues From the Past

The discovery took place in a limestone cave in the southern Dominican Republic, an area known for its sinkholes and underground cave systems. Hispaniola, which includes Haiti and the Dominican Republic, has a landscape dominated by limestone bedrock. In many places, soil is thin or almost nonexistent, exposing caves and underground chambers at regular intervals.

The cave itself was first identified as an important fossil site by Juan Almonte Milan, curator of paleobiology at the Dominican Republic’s Museo Nacional de Historia Natural. Layers of fossil deposits suggested long-term animal activity, making it a prime location for scientific study.

Lazaro Viñola López, a postdoctoral researcher at the Field Museum in Chicago and lead author of the study, explored the cave while working on his PhD research with the University of Florida and the Florida Museum of Natural History. Reaching the fossil layers required rappelling down into the cave and navigating narrow tunnels, an environment also home to tarantulas and other cave-dwelling creatures.

Thousands of Years of Owl Activity

As researchers examined the cave’s contents, a clear pattern emerged. The site had been used by owls for hundreds or even thousands of years. Owls regularly regurgitate pellets containing the bones of their prey, and over time, these pellets accumulated on the cave floor.

The fossil layers contained bones from more than 50 species, including rodents, sloths, birds, reptiles, turtles, and even crocodiles. There were also fossils from the owls themselves. Periods of heavy rainfall had deposited carbonate layers between fossil beds, creating a natural timeline of activity stretching back tens of thousands of years.

For paleontologists, this was already a treasure trove of information about ancient Caribbean ecosystems. But the most surprising discovery was still hidden in plain sight.

Something Unusual Inside the Bones

While cleaning fossilized mammal jaws collected from the cave, Viñola López noticed something odd. The empty tooth sockets in some of the jaws were filled with sediment that didn’t look natural.

Instead of being rough or randomly packed, the sediment was smooth, concave, and carefully shaped. This pattern appeared again and again across multiple specimens. It didn’t resemble normal geological infill.

Viñola López was reminded of something he had seen years earlier while working on a fossil dig in Montana: ancient wasp cocoons, made of dried mud and shaped into small chambers where larvae developed.

That comparison raised an important question. Could these structures inside the bones also be insect nests?

Confirming the Presence of Bee Nests

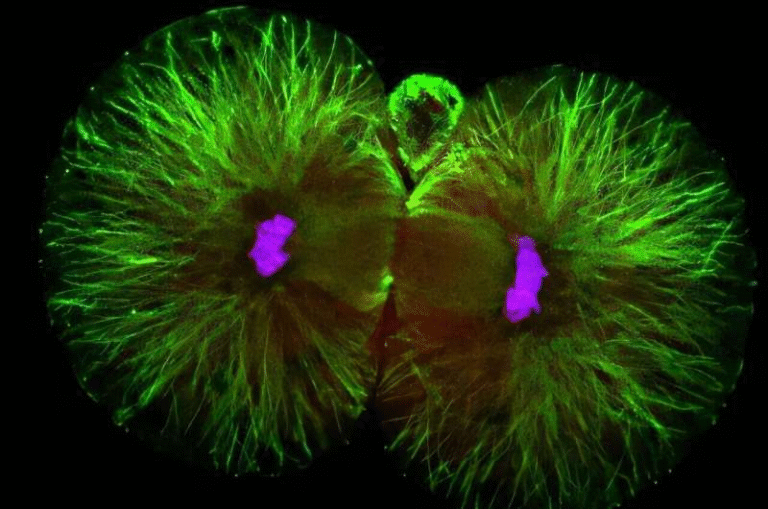

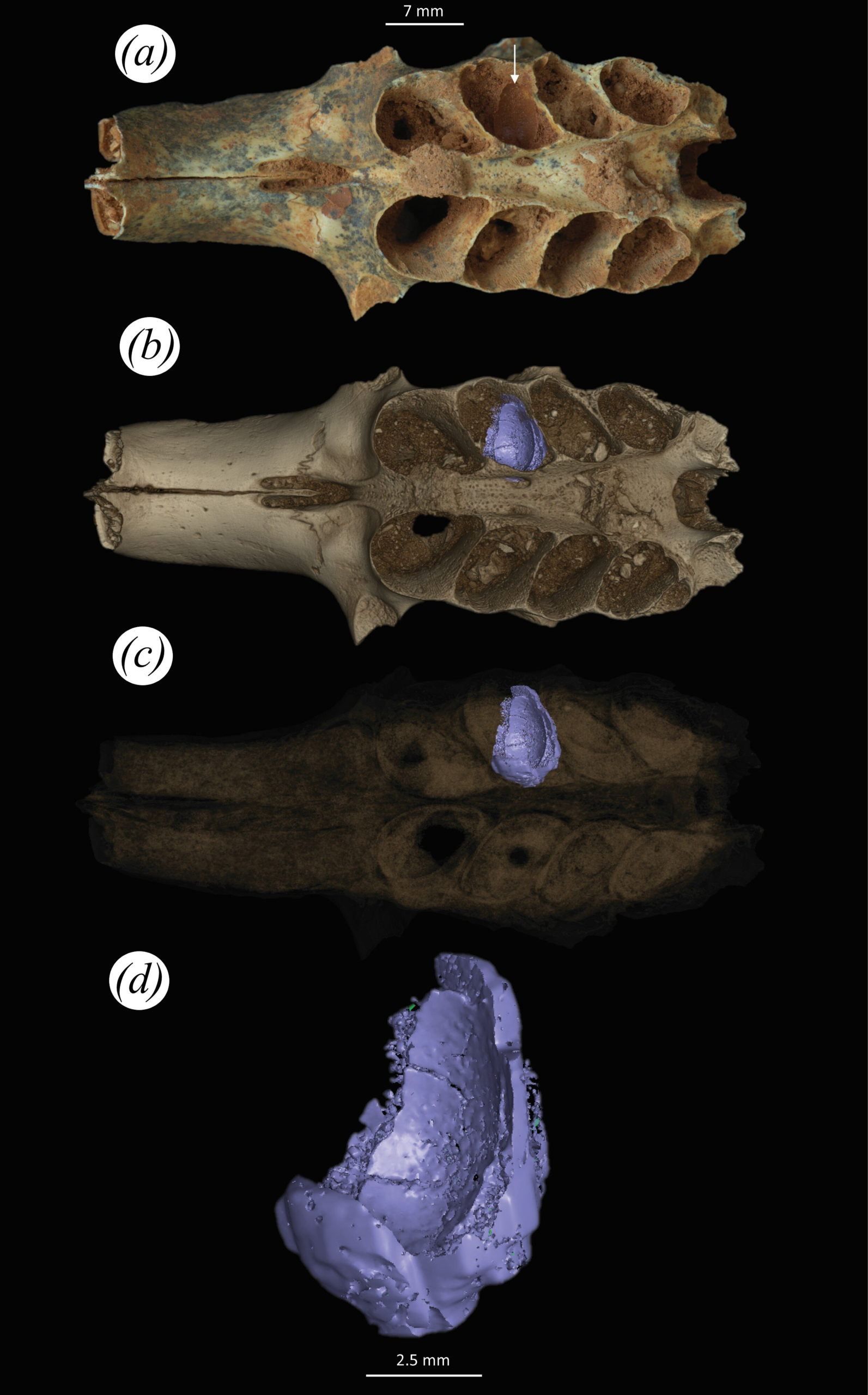

To investigate further without damaging the fossils, the research team used CT scanning technology. By X-raying the bones from multiple angles, they were able to create detailed 3D images of the sediment inside the tooth sockets.

The scans revealed that the structures were not random at all. They closely matched the shape and organization of mud nests built by modern solitary bees. Some of the nests even contained grains of fossilized pollen, likely left behind as food for developing larvae.

Each nest was tiny, smaller than the eraser on a pencil, and appeared to be an individual chamber for a single bee egg. The researchers concluded that the bees likely mixed saliva with fine sediment to construct these nests, sealing them inside the protective cavities of the bones.

Why Bones Made the Perfect Nursery

Most people think of bees as living in hives or underground burrows, but that only applies to a small fraction of species. Most bees are solitary, and they rely on small, protected cavities to lay their eggs.

In regions like southern Hispaniola, loose soil is scarce due to the limestone terrain. That limitation may have pushed ancient bees to seek alternative nesting sites. The owl-delivered bones provided ready-made cavities that were dry, stable, and well-protected.

Using bones may also have offered protection from predators, such as parasitic wasps, which often attack exposed nests. Inside a jawbone buried in a cave, bee larvae would have had a much better chance of survival.

Naming a New Type of Fossil Evidence

No actual bee bodies were found in the cave. That isn’t surprising, since hot, humid cave conditions are poor for preserving delicate insects. Without physical remains, researchers couldn’t identify the exact species of bee responsible.

However, the nests themselves were distinctive enough to be classified as a new trace fossil, which records an organism’s behavior rather than its body. The team named the nests Osnidum almontei, in honor of Juan Almonte Milan, who discovered the cave and has spent decades studying the region’s paleontology.

It remains unclear whether the bees that built these nests are extinct or still alive today. Many Caribbean bee species are poorly studied, and it’s possible their modern descendants still exist.

Why This Discovery Matters

This finding represents the first documented case of bees nesting inside animal bones, expanding what scientists know about insect behavior in deep time.

It also highlights the importance of careful fossil examination. If the unusual sediment had been dismissed as dirt and scrubbed away, this rare insight into ancient ecosystems would have been lost.

The study shows how insects, birds, mammals, and geological conditions can interact in complex ways. Owls unintentionally created nesting opportunities for bees, which in turn left behind trace fossils that survived for tens of thousands of years.

What This Tells Us About Bees

Bees are often discussed in the context of pollination and modern conservation, but discoveries like this remind us that they have a long evolutionary history of adaptability. Solitary bees, in particular, are known for using unconventional materials and locations for nesting, including wood, soil, plant stems, and even snail shells.

This fossil evidence pushes that adaptability further back in time and into an entirely new category: bones.

A Broader Window Into Ancient Ecosystems

Beyond bees, the study reinforces the value of trace fossils for understanding ancient environments. Even when animal bodies are not preserved, their behaviors can still leave lasting marks.

By paying attention to small details, scientists can reconstruct entire ecological networks, revealing how species influenced one another in ways that are still relevant today.

Research paper:

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.251748