Scientists Discover How the Ocean’s Most Abundant Bacteria Split Into Distinct Ecological Groups

The world’s oceans are filled with microscopic life that quietly keeps marine ecosystems running, and among the most important of these organisms are SAR11 marine bacteria. A new study led by researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) has uncovered crucial insights into how these incredibly abundant bacteria diversify into stable, ecologically distinct groups, reshaping how scientists understand one of the ocean’s most influential life forms.

SAR11 bacteria are not rare or obscure. They are widely considered the most abundant bacteria in the ocean, and possibly among the most abundant organisms on Earth. They play a central role in recycling carbon and nutrients, processes that support the entire marine food web and influence the global climate. Because of their importance, understanding how SAR11 populations function and adapt is key to predicting how the ocean will respond to climate change, pollution, and warming waters.

Why SAR11 Bacteria Matter So Much

SAR11 bacteria are tiny, streamlined cells that thrive in nutrient-poor seawater. Despite their small size, their sheer numbers make them powerful drivers of marine biogeochemical cycles. They process dissolved organic carbon, recycle nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, and help regulate the flow of energy through ocean ecosystems.

For years, scientists treated SAR11 as a largely uniform group. While researchers knew there was genetic variation within SAR11, it was difficult to connect those genetic differences to real ecological roles in the ocean. One major reason for this gap in understanding is that SAR11 bacteria are notoriously difficult to grow in laboratory conditions, limiting direct study.

A Major Shift in Understanding SAR11 Diversity

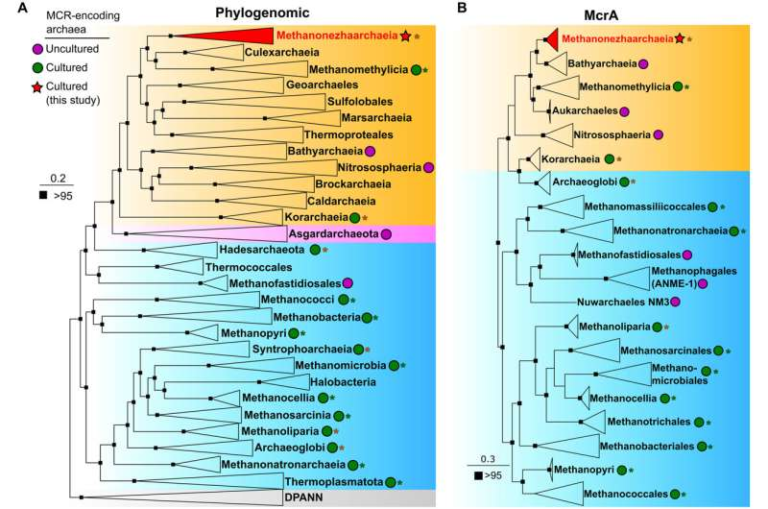

The new study, published in Nature Communications, challenges the long-standing idea that SAR11 behaves as a single, homogeneous population. Instead, the research shows that SAR11 is divided into distinct and stable ecological units, each adapted to specific marine environments.

These ecological groups can be thought of as specialized teams rather than interchangeable players. Some groups are better suited to coastal waters, while others are adapted to the open ocean. These differences are not random or temporary. The study demonstrates that SAR11 groups differ in habitat preference, gene content, and evolutionary history, indicating long-term ecological specialization.

This discovery reveals that one of the ocean’s most important biological engines is far more complex and structured than previously believed.

Kāneʻohe Bay as a Natural Laboratory

A key strength of this research comes from its use of Kāneʻohe Bay, Hawaiʻi, as a model system. Kāneʻohe Bay is uniquely suited for studying microbial ecology because it has been monitored for years through the Kāneʻohe Bay Time-series (KByT) program. This long-term dataset includes detailed environmental measurements paired with consistent microbial sampling.

The bay also contains sharp environmental gradients over small spatial scales, such as differences between coastal and offshore waters. These conditions allowed researchers to observe how closely related bacteria adapt to slightly different environments, offering rare insight into microbial diversification.

By cultivating new SAR11 strains from Kāneʻohe Bay and linking them directly to environmental data, researchers were able to connect genomes to real-world ecological behavior, something that has been extremely difficult to achieve for this bacterial group.

New Genomes, Global Connections

One of the most significant achievements of the study was the successful cultivation and sequencing of new SAR11 isolate genomes. These newly grown strains dramatically expanded the number of available SAR11 genomes for analysis.

The research team then compared these genomes with marine metagenomic data from ocean samples around the world. This global comparison showed that the ecological groupings identified in Kāneʻohe Bay are not local anomalies. Instead, they reflect global patterns that hold across diverse marine environments.

In other words, the ecological structure seen in Hawaiʻi mirrors how SAR11 populations are organized throughout the world’s oceans. This finding provides a common framework for studying SAR11 diversity on a planetary scale.

Clear Ecological and Evolutionary Structure

The study reveals that SAR11 diversity follows clear evolutionary lines rather than forming a random genetic continuum. These ecologically distinct groups are stable over time and show consistent associations with specific environmental conditions.

This structure suggests that ecological selection, not chance, is driving diversification within SAR11. Different groups have evolved genetic traits that allow them to thrive in particular habitats, reinforcing their separation over evolutionary timescales.

By identifying these units, scientists can now study SAR11 diversity in a more meaningful way, focusing on functional differences rather than treating all SAR11 bacteria as equivalent.

Why This Discovery Is Important for Climate Science

Because SAR11 bacteria are deeply involved in carbon cycling, understanding their diversity has direct implications for climate research. Different SAR11 groups may respond differently to changes in temperature, nutrient availability, or pollution.

If climate change alters ocean conditions, some SAR11 groups may become more dominant while others decline. These shifts could affect how efficiently the ocean stores or releases carbon, influencing global climate feedbacks.

By recognizing that SAR11 consists of specialized ecological units, scientists can build more accurate models of ocean processes and better predict how marine ecosystems will respond to future environmental stress.

A Broader Look at Marine Microbial Life

This research also highlights a broader lesson in marine microbiology. Even organisms that appear simple and uniform at first glance can harbor hidden complexity. Microbial life in the ocean is shaped by subtle environmental differences, evolutionary pressures, and long-term adaptation.

Studies like this show why long-term monitoring programs and cultivation efforts remain essential. Without years of data from places like Kāneʻohe Bay and the painstaking work of growing difficult microbes, these ecological patterns would remain invisible.

Additional Context: What Are Pelagibacterales?

SAR11 bacteria belong to the bacterial order Pelagibacterales, a group known for extreme genome streamlining. Their genomes are among the smallest of any free-living organisms, containing only the genes necessary for survival in nutrient-poor environments.

This streamlined lifestyle makes SAR11 incredibly efficient but also difficult to study. Small genomes mean fewer obvious markers for distinguishing species, which is one reason their ecological diversity remained hidden for so long.

The new research helps resolve this challenge by combining cultured genomes with environmental DNA, offering a clearer view of how Pelagibacterales are organized in nature.

What This Means Going Forward

The findings from this study provide a powerful new framework for studying marine bacteria. Researchers can now ask more targeted questions about how specific SAR11 groups interact with their environment, respond to stress, and influence ocean chemistry.

More broadly, the work underscores the idea that microbial diversity matters, even within groups that dominate ecosystems numerically. Understanding that diversity is essential for managing and protecting ocean health in a rapidly changing world.

As scientists continue to explore the ocean at the microscopic level, studies like this remind us that some of the most important discoveries happen far beyond what the human eye can see.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67043-6