New Research Explains Why Malaria Parasites Are Forced to Limit the Damage They Cause to Humans

Understanding why parasites harm their hosts has long been a central question in evolutionary biology. If killing or severely weakening a host seems counterproductive, why does it happen at all? A new study focused on human malaria parasites offers a detailed, model-based answer. Using mathematical modeling rather than assumptions, researchers have uncovered how internal biological tradeoffs constrain how dangerous malaria parasites can become—and why they may never evolve toward maximum harm.

The study centers on Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest malaria parasite affecting humans. By closely examining how this parasite balances replication, transmission, and survival, the research provides new insight into parasite evolution and helps explain real-world infection patterns that older models struggled to predict.

The Core Question: Why Don’t Malaria Parasites Become More Lethal?

From an evolutionary standpoint, a parasite’s success is measured by its ability to spread to new hosts. Intuitively, one might think faster replication inside the host would always be beneficial. However, replication often comes at a cost—namely, damage to the host, which can shorten the infection or kill the host before transmission occurs.

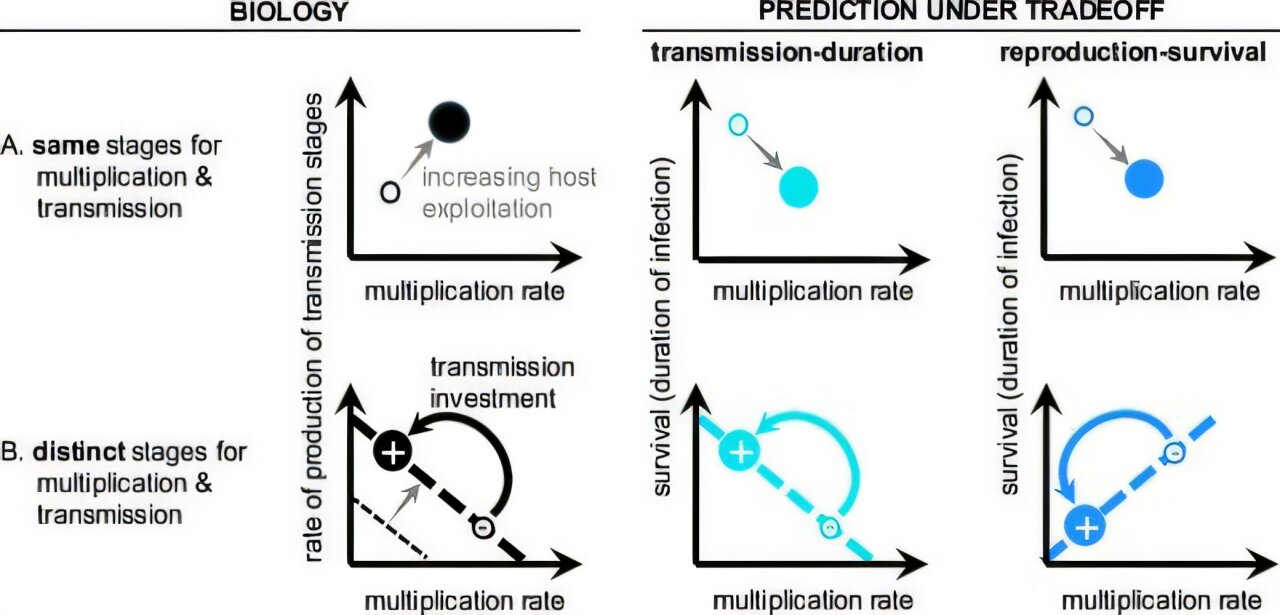

Traditionally, many models of parasite evolution assumed a simple tradeoff between how fast a parasite transmits and how long it can stay inside a host. These models suggested parasites should evolve toward an optimal balance between spreading quickly and keeping the host alive long enough to pass the infection along.

The new study challenges that assumption.

Instead of assuming a transmission–duration tradeoff, the researchers built a model that explicitly includes the human immune system, particularly its response to malaria parasites during infection. This shift turns out to be crucial.

A Closer Look at the Malaria Parasite Life Cycle

To understand the study’s findings, it helps to look at the unusually complex life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum.

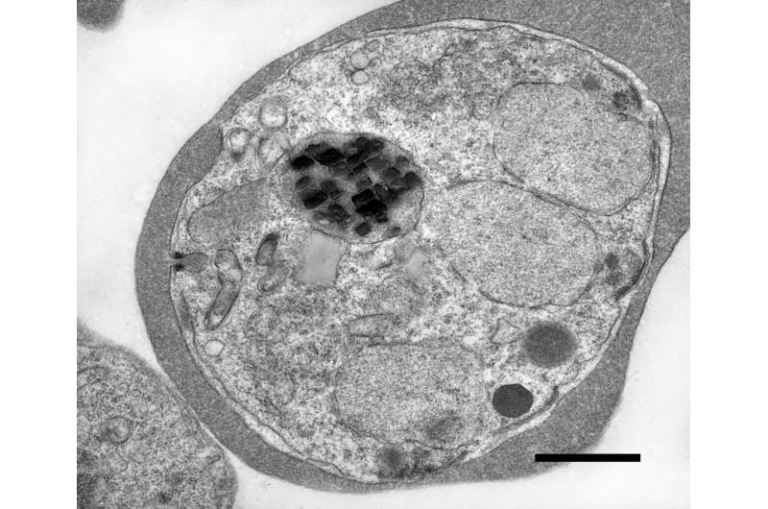

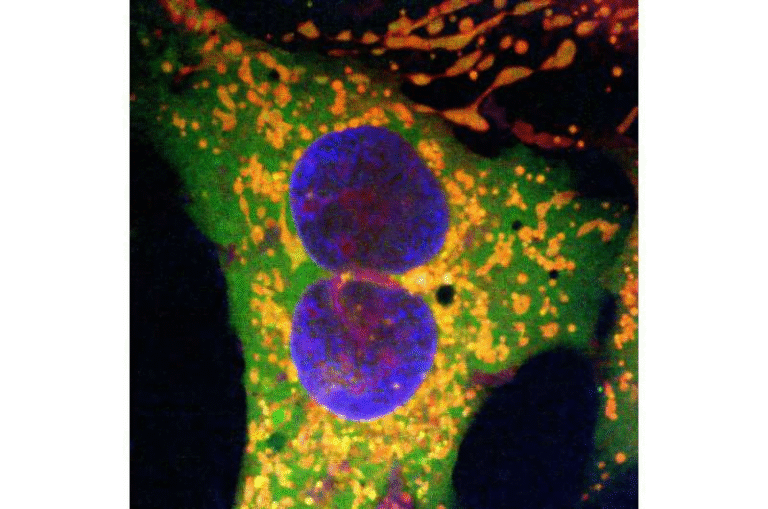

Malaria parasites alternate between human hosts and mosquito hosts. When an infected mosquito bites a human, parasites enter the bloodstream and travel to the liver, where they multiply quietly at first. After leaving the liver, they invade red blood cells and begin asexual replication.

This red blood cell stage is when malaria symptoms appear. Parasites repeatedly replicate, burst out of blood cells, and infect new ones, causing fever, anemia, and potentially severe disease. Importantly, these replicating forms cannot infect mosquitoes.

For transmission to occur, some parasites must shift into a different form called gametocytes, which are sexual transmission stages. These gametocytes circulate in the blood and can infect mosquitoes when they take a blood meal, allowing the parasite to continue its life cycle.

Here’s where the key tradeoff appears:

The parasite can replicate inside the host or invest in producing gametocytes, but it cannot fully optimize both at the same time.

Replication Versus Transmission: A Biological Tradeoff

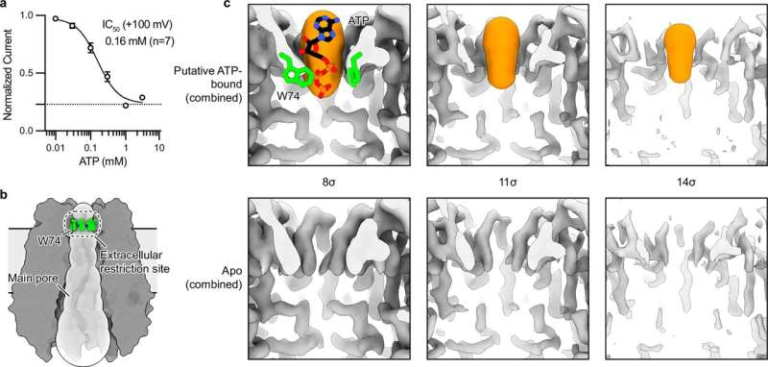

The study shows that replication and transmission occur simultaneously, drawing from the same limited pool of resources. When parasites invest more heavily in gametocyte production, they have fewer resources available for replication within red blood cells.

This tradeoff matters because the human immune system primarily targets the replicating stages of the parasite. Strong replication attracts stronger immune responses, which can reduce parasite survival inside the host.

By incorporating this immune pressure into the model, the researchers discovered a reproduction–survival tradeoff that had not been explicitly modeled before.

In simple terms:

- More replication increases harm to the host but provokes stronger immune attacks.

- More transmission investment reduces replication, limits immune targeting, and lowers parasite-induced damage.

A Surprising Result That Flips Old Assumptions

One of the most interesting outcomes of the model is that it predicts a pattern opposite to what many older models expected.

Under traditional transmission–duration tradeoff assumptions, reducing transmission investment was thought to shorten infections. However, the new model shows that over-investing in transmission can actually reduce infection persistence.

When parasites put too many resources into gametocytes:

- They replicate less effectively.

- They struggle to maintain infection over time.

- They become less harmful to the host.

Conversely, parasites that moderate their investment in transmission can maintain both a longer infection and a higher cumulative chance of transmission.

This explains why malaria parasites appear to invest less in transmission than earlier models predicted—a pattern that aligns much more closely with real-world observations from human infections.

Why Host Immunity Changes Everything

A major strength of this study is its explicit inclusion of host immunity, something often simplified or ignored in earlier models.

Human immune responses do not act uniformly across all parasite stages. Instead, they mainly target parasites during the asexual replication phase in red blood cells. Gametocytes, while not invisible to the immune system, are less directly affected.

This selective pressure creates a built-in constraint on parasite evolution. Parasites that replicate too aggressively trigger immune responses that limit their own survival. Parasites that shift too heavily toward transmission lose the ability to sustain infection.

The result is a narrow evolutionary path where parasites are forced into moderation.

What This Means for Parasite Virulence

Virulence—how much harm a parasite causes—is not an accidental byproduct. According to this research, it is a constrained outcome shaped by competing biological demands.

Parasites with higher transmission investment are generally less harmful because they replicate less inside the host. This limits tissue damage, reduces immune activation, and ultimately restrains disease severity.

The model suggests that parasite fitness is constrained not by a single tradeoff, but by a network of interacting pressures involving replication, immunity, survival, and transmission.

Implications for Malaria Control and Public Health

Understanding these evolutionary constraints is not just an academic exercise. It has direct implications for malaria control strategies, including vaccines and drug treatments.

If interventions shift parasite behavior—for example, by targeting replication more aggressively—they could unintentionally push parasites toward greater transmission investment. However, the study suggests that such shifts may not automatically lead to increased virulence, as parasites remain limited by survival constraints.

By understanding what already restricts parasite evolution, researchers can make better predictions about how malaria might respond to future interventions.

Broader Lessons About Parasite Evolution

Beyond malaria, this study offers broader insight into host–parasite relationships. It shows that parasite evolution cannot be fully understood without considering:

- Stage-specific immune responses

- Resource allocation within hosts

- Life cycle complexity

Simple assumptions may miss critical dynamics that determine real-world outcomes.

Final Thoughts

This research provides a clearer explanation for why malaria parasites do not evolve into maximally destructive organisms. Through a careful modeling approach that accounts for immunity and life cycle tradeoffs, the study reveals that parasites are boxed in by their own biology.

Rather than choosing how harmful to be, malaria parasites are forced into compromise, balancing replication, transmission, and survival in ways that ultimately limit the damage they cause to humans.

Research paper:

https://academic.oup.com/evolut/advance-article/doi/10.1093/evolut/qpaf238/8342153