Genetic Teamwork Between Plant Genomes Could Hold the Key to Climate-Resilient Crops and Forests

Plants may look simple on the outside, but inside their cells, an intricate genetic collaboration is constantly at work. New research led by plant scientists at Penn State suggests that how well different parts of a plant’s genetic system cooperate could play a major role in determining how well plants survive, grow, and adapt in a changing climate. The study focuses on something called genetic teamwork, specifically how different plant genomes interact with one another, and why this interaction matters more than scientists once realized.

Plants Carry More Than One Genome

Unlike animals, plants don’t rely on just a single genetic instruction set. Each plant cell contains three distinct genomes. The first is the nuclear genome, stored in the nucleus and responsible for most of the plant’s traits. The second is the chloroplast genome, found inside chloroplasts, the organelles that drive photosynthesis. The third genome resides in the mitochondria, which are responsible for cellular respiration and energy production.

This study focused on the relationship between the nuclear genome and the chloroplast genome because of their direct role in photosynthesis, the process plants use to convert sunlight into chemical energy. When these two genomes work in sync, plants tend to function efficiently. When they don’t, problems can arise.

Why Hybrid Plants Are So Important

The researchers examined hybrid plants, which form when two closely related species interbreed. While hybridization is common in nature and can sometimes produce stronger or more adaptable offspring, it can also disrupt genetic coordination. When genes that evolved together in one species suddenly have to cooperate with genes from another species, their interaction may not be seamless.

This phenomenon is known as cytonuclear mismatch. It happens when nuclear genes inherited from one species do not work well with chloroplast genes inherited from another. The study set out to understand how often this mismatch occurs in nature and how it affects plant performance across different environments.

The Trees at the Center of the Study

The research focused on two tree species native to North America’s Pacific Northwest: black cottonwood and balsam poplar. These species naturally overlap in range and hybridize across a vast geographic region stretching from Alaska to Wyoming, including parts of Canada such as the Yukon, British Columbia, and Alberta.

Within this broad area, scientists identified six distinct east–west hybrid contact zones, regions where the two species frequently interbreed. These zones provided an ideal natural laboratory to study how nuclear and chloroplast genomes mix, separate, or stay together across different environments.

A Massive Sampling Effort

To capture the full picture, the research team collected vegetative cuttings from 574 individual trees across the hybrid zones. These cuttings, essentially branches capable of growing into full plants, were sent to collaborators at Virginia Tech, where they were propagated in controlled greenhouse conditions.

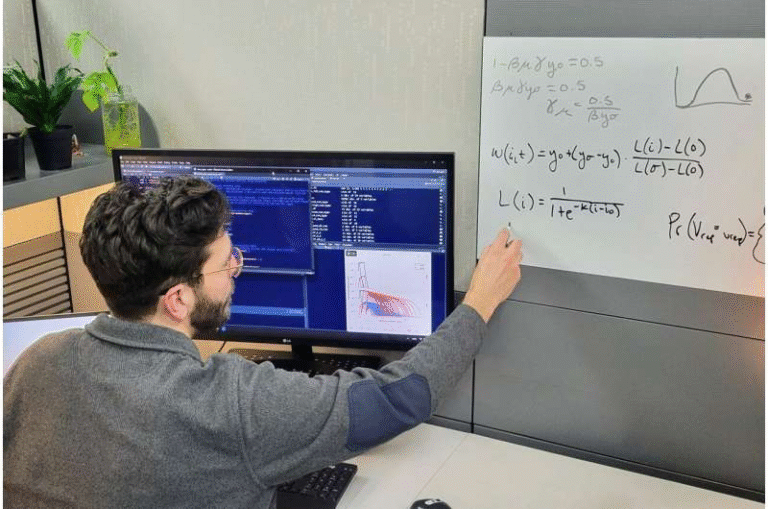

Once the plants were established, researchers extracted DNA and conducted detailed genetic analyses, sequencing both the entire nuclear genome and the chloroplast genome of each tree. This allowed them to precisely determine the ancestry of each genome and identify genes involved in chloroplast function.

The scale of this analysis required immense computing power, which was provided by Penn State’s Roar Collab Cluster, a high-performance computing facility capable of handling massive genomic datasets.

Testing Plants in the Real World

Genetic data alone wasn’t enough. To understand how these genetic combinations affect real plant performance, the team planted genetically identical copies of the trees in common garden experiments located in Virginia and Vermont. By growing the same genotypes in different environments, researchers could directly measure how nuclear–chloroplast interactions influenced traits like photosynthetic efficiency and nutrient use.

This approach made it possible to separate genetic effects from environmental ones, revealing how specific genome combinations respond to different climate conditions.

What the Researchers Found

One of the most striking findings was that nuclear and chloroplast genomes do not always stay together, even when they evolved as a coordinated pair in a parent species. Across much of the hybrid zone, chloroplast genomes and their interacting nuclear genes mixed freely.

However, in regions with strong environmental gradients, such as transitions from warmer coastal climates to colder boreal or mountainous environments, natural selection appeared to favor genome combinations that had evolved together. In these areas, environmental pressure encouraged genetic teamwork, keeping compatible nuclear and chloroplast genes linked.

Performance Depends on Genetic Compatibility

The study also showed that cytonuclear mismatch directly affects plant performance. Trees whose nuclear and chloroplast ancestries did not align often showed reduced photosynthetic efficiency, meaning they were less effective at converting sunlight into energy.

This effect was observed across multiple environments but became especially pronounced in warmer conditions, such as those in Virginia. In some cases, mismatched genomes performed better in specific environments, highlighting that genetic compatibility can have context-dependent effects.

What This Means for Climate Change

As climates shift, plants are increasingly exposed to conditions they are not fully adapted to. Hybridization may become more common as species ranges move and overlap. This research suggests that whether hybrid plants thrive or struggle may depend on how well their genomes cooperate.

Understanding which genetic combinations work best could help scientists predict which plant populations are most likely to survive under future climate scenarios.

Implications for Plant Breeding and Conservation

The findings have important implications for plant breeding, forestry, and conservation. Breeding programs often focus on individual genes or traits, but this research highlights the importance of considering genome-level interactions.

By selecting nuclear and chloroplast combinations that function well together, breeders may be able to develop more resilient crops and trees. This could be especially valuable for long-lived species like forest trees, which must endure decades of environmental change.

A Broader Lesson About Plant Evolution

Beyond practical applications, the study provides new insight into how plants evolve. It shows that evolution doesn’t just act on individual genes, but also on relationships between genomes. These interactions can shape how species adapt, hybridize, and respond to environmental stress.

As researchers continue to explore these hidden layers of genetic cooperation, it’s becoming clear that plant survival is not just about having the right genes, but about having genes that work well together.

Research Paper:

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2025.1239