AI Researchers Build a Scientific Sandbox to Explore How Vision Systems Evolve

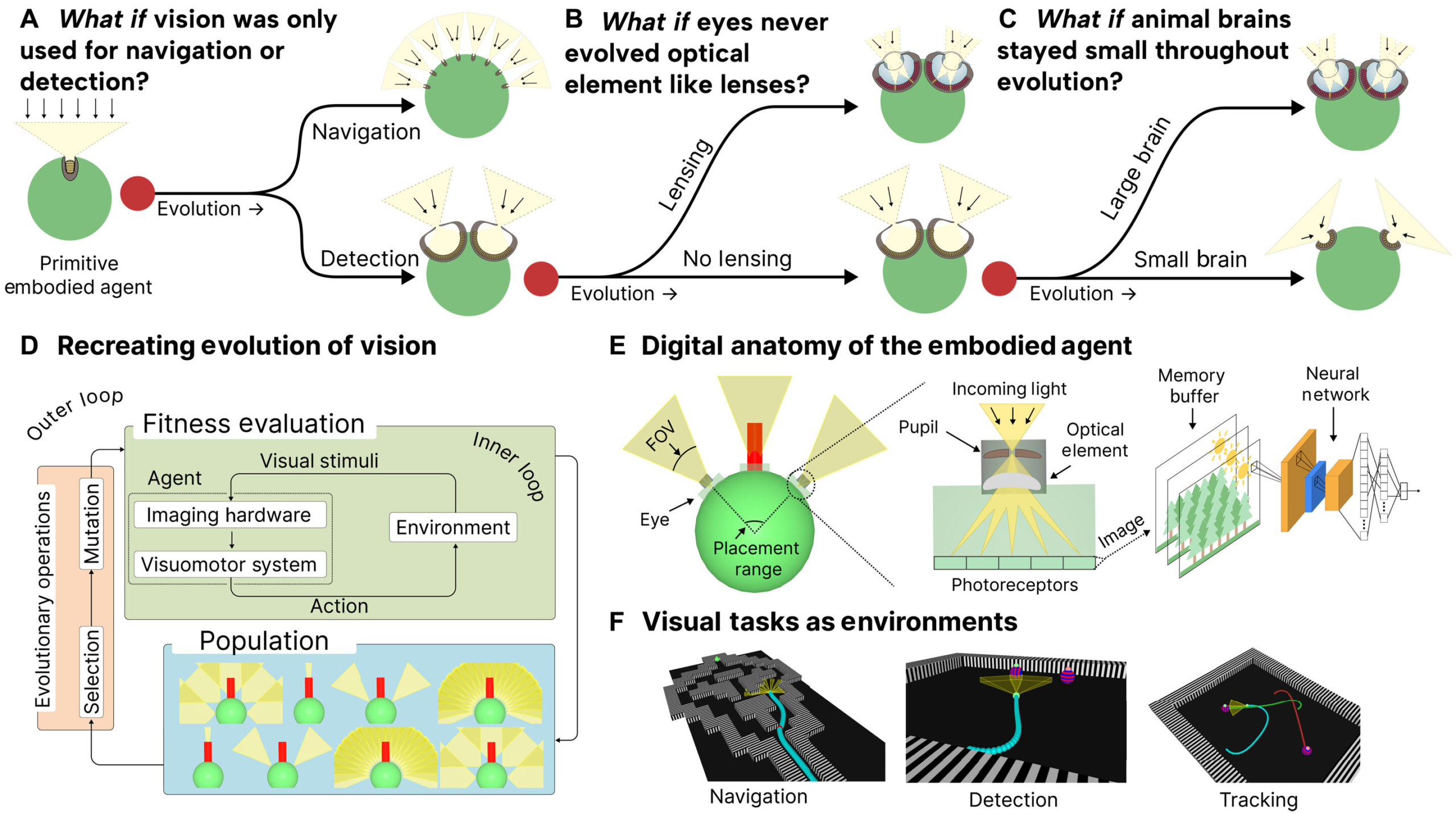

Researchers at MIT and collaborating institutions have created a new computational framework that allows scientists to explore one of biology’s most enduring questions: why do different creatures see the world the way they do? Instead of relying solely on fossils or comparative biology, this new approach uses artificial intelligence and simulated evolution to recreate how vision systems might emerge under different environmental pressures.

At its core, the framework acts as a scientific sandbox. Within this sandbox, embodied AI agents evolve visual systems over many generations while interacting with simulated environments. By adjusting tasks and environmental constraints, researchers can observe how different kinds of “eyes” emerge, offering insights into why nature produced such a wide diversity of vision systems, from simple light-sensitive patches to complex camera-style eyes like those found in humans.

Recreating Evolution in Silico

Studying vision evolution directly is nearly impossible. Scientists cannot rewind time to observe how ancient organisms adapted their eyes to survive in changing environments. This limitation motivated the MIT-led team to ask whether evolution could be recreated computationally, even if only in simplified form.

Their solution was to design AI agents that exist in simulated worlds. These agents are embodied, meaning they perceive their environment through visual sensors and act within it. Over successive generations, the agents evolve both their visual hardware and the neural systems that process visual information.

By changing the structure of the simulated world and the tasks agents must complete, researchers can generate different evolutionary “paths.” This approach allows them to test what-if scenarios that are otherwise unreachable through experiments in nature.

Turning Cameras into Evolutionary Building Blocks

To build this sandbox, the researchers broke down vision systems into their most fundamental components. Elements typically found in cameras—such as sensors, lenses, apertures, and processing units—were converted into parameters that AI agents could modify and optimize over time.

Each agent begins life with the simplest possible visual system: a single photoreceptor that detects light from the environment. Alongside this photoreceptor is a neural network responsible for processing incoming visual signals.

As agents interact with their environment, they learn through reinforcement learning, a trial-and-error process where successful behaviors are rewarded. Over many generations, evolution takes place through a genetic encoding mechanism, which controls how visual systems develop and change.

The researchers divided these genetic traits into three broad categories:

- Morphological genes, which determine eye placement and how the agent views its surroundings

- Optical genes, which influence how light is captured, including the number and arrangement of photoreceptors

- Neural genes, which control how much learning and processing capacity the agent has

Mutations in these genes allow new visual designs to emerge, mimicking the variability seen in biological evolution.

Tasks Shape the Eyes That Evolve

One of the most striking findings from the experiments is how strongly tasks influence eye design. When agents are placed in environments where navigation is the primary challenge—such as moving efficiently through space—certain types of vision systems tend to emerge.

In these scenarios, agents often evolve compound-eye-like systems, composed of many individual visual units. These eyes favor wide fields of view and spatial awareness rather than high detail, closely resembling the eyes of insects and crustaceans.

In contrast, when agents are tasked with object discrimination, such as identifying food items or distinguishing between similar objects, a very different outcome occurs. These agents are more likely to evolve camera-type eyes, featuring centralized vision, higher acuity, and structures analogous to irises and retinas.

This clear relationship between task demands and eye structure reinforces the idea that vision systems are not optimized for general perfection, but rather for specific survival needs.

Constraints Matter as Much as Capability

The sandbox does not allow agents unlimited resources. Each simulated environment includes constraints similar to those found in nature. For example, agents may be limited in the number of pixels their visual sensors can have or the amount of information their neural systems can process at once.

These constraints play a crucial role in shaping evolution. The experiments revealed that bigger brains are not always better. Once an agent reaches a certain limit in how much visual data it can receive, adding more processing power provides little to no benefit.

From an evolutionary perspective, excess brain capacity would represent a waste of energy and resources. This result mirrors biological reality, where organisms evolve systems that are good enough for survival rather than maximally complex.

Why This Framework Matters for Science

The scientific sandbox opens new doors for evolutionary research. Instead of relying solely on indirect evidence, scientists can now systematically test hypotheses about how vision might have evolved under different conditions.

Questions that were once purely speculative—such as whether complex eyes are inevitable or whether simpler designs could dominate under certain pressures—can now be explored experimentally, albeit in a simulated setting.

Importantly, the framework is not limited to vision alone. While the current work focuses on eyes and visual processing, the same principles could be extended to study other sensory systems or even broader aspects of embodied intelligence.

Practical Applications Beyond Biology

This research is not just about understanding nature. The findings could directly influence the design of artificial vision systems. Engineers building robots, drones, or wearable devices often face trade-offs between performance, energy efficiency, and manufacturing complexity.

By observing which vision systems evolve naturally under specific tasks, designers can create task-specific sensors that are more efficient than general-purpose cameras. For example, a navigation-focused robot may benefit from wide-field, low-resolution vision rather than expensive high-resolution cameras.

The sandbox could also help identify entirely new visual architectures that do not exist in nature but perform well under certain constraints, expanding the toolkit available to engineers and designers.

Looking Ahead: Expanding the Sandbox

The research team plans to further develop this framework. One future goal is to integrate large language models, which could allow users to ask high-level questions and automatically configure simulations to explore those ideas.

By making the sandbox more accessible, the researchers hope to inspire broader use of computational evolution as a scientific tool. Rather than focusing narrowly on individual hypotheses, this approach encourages wide-ranging exploration across many possible evolutionary scenarios.

Understanding Vision Through Computation

While no simulation can perfectly capture the full complexity of biological evolution, this scientific sandbox represents a powerful new way to study vision. It allows researchers to recreate key aspects of evolutionary pressure, constraint, and adaptation in a controlled environment.

In doing so, it brings scientists one step closer to understanding why humans and other animals see the world the way they do, and how different visual systems might have emerged if history had unfolded just a little differently.

Research paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ady2888