How Ultra-Processed Foods Are Forcing Gut Bacteria to Rapidly Evolve

Scientists have long known that diet shapes the gut microbiome, but a new study from researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles shows just how fast and dramatically this influence can play out. According to findings published in Nature, gut bacteria are rapidly evolving to digest starches found in ultra-processed foods, and this evolution has happened in just a few decades.

This research offers rare, real-time evidence of natural selection acting on microbes living inside the human body. It also highlights an important divide between industrialized and non-industrialized populations, where gut bacteria appear to be adapting to very different dietary environments.

Gut Bacteria Are Adapting at an Astonishing Speed

The UCLA research team analyzed the genomes of nearly three dozen species of human gut bacteria using genetic data collected from people around the world. What they found was striking: certain gene variants that help bacteria digest industrially produced starches have become widespread extremely quickly in some bacterial species.

These starches, commonly found in ultra-processed foods, are new in evolutionary terms. Many of them, such as maltodextrin, only became common in human diets during the mid-20th century. Because these food ingredients have existed for such a short time, the rapid dominance of starch-digesting genes strongly suggests intense evolutionary pressure.

In other words, gut bacteria are not just passively responding to modern diets — they are actively evolving to take advantage of them.

What Makes Ultra-Processed Starches Different

Ultra-processed foods often contain starches that are chemically modified or broken down from their original plant sources. One key example highlighted in the study is maltodextrin, a starch derivative made from cornstarch and widely used in processed foods since the 1960s.

Unlike starches found naturally in foods like cassava, breadfruit, or whole grains, maltodextrin is highly refined, easy to digest, and rapidly available as an energy source. This makes it an attractive target for gut microbes looking to gain a competitive edge.

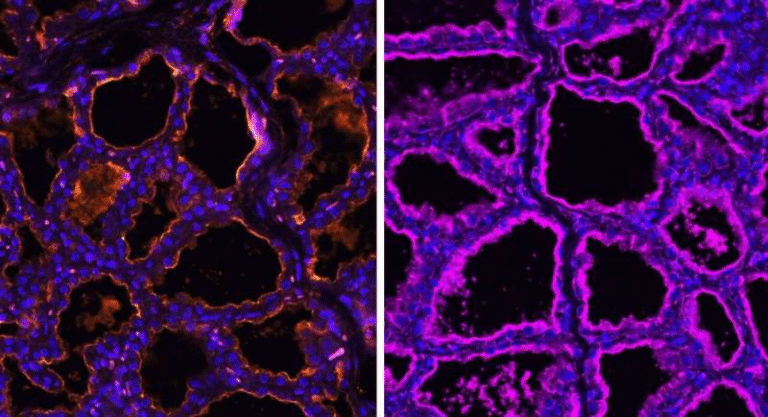

The researchers identified a specific gene linked to the ability to digest maltodextrin that has undergone a strong selective sweep — meaning it rapidly rose in frequency — but only in industrialized populations.

Industrialized vs Non-Industrialized Populations

One of the most important findings of the study is that gut bacteria are evolving differently depending on where people live.

In industrialized regions, where diets are heavy in ultra-processed foods, certain genes related to starch digestion have become dominant. In non-industrialized populations, where diets are typically richer in whole and traditional foods, different genes appear to be under selection.

This suggests that modern food systems are creating distinct evolutionary environments inside the human gut. Rather than a single global microbiome trend, there are multiple evolutionary paths unfolding simultaneously.

The maltodextrin-related gene stood out because it was sweeping through bacterial genomes only in industrialized populations, making it a clear marker of modern dietary influence.

How Researchers Detected Rapid Evolution

To uncover these patterns, the UCLA team developed a new statistical method designed to detect gene-specific selective sweeps. This approach identifies tiny regions of DNA that have become unusually uniform across many bacterial strains, standing out against an otherwise highly diverse genetic background.

This matters because strains of the same bacterial species can be extremely different genetically. In fact, some strains of common bacteria like E. coli differ from each other as much as humans differ from chimpanzees. Despite this diversity, the researchers found shared fragments of DNA appearing again and again across individuals.

These shared fragments are strong evidence that certain genes are being favored by natural selection.

The Role of Horizontal Gene Transfer

The key mechanism driving this rapid adaptation is horizontal gene transfer. Unlike humans, bacteria do not rely solely on reproduction to pass on genetic traits. Instead, they can acquire useful genes directly from other bacteria.

Horizontal gene transfer can happen in several ways. Bacteria may absorb free DNA from their environment, exchange genes through viruses that infect them, or physically connect to other bacteria and pass genetic material across.

This process is already well known for spreading antibiotic resistance, but its widespread role in shaping the gut microbiome had not been fully appreciated until now.

What surprised researchers was how pervasive this gene sharing appears to be, especially considering that humans usually carry only a few strains of each bacterial species, and those strains tend to remain stable for years.

A Major Unanswered Question

One of the biggest mysteries raised by the study is how these genes spread so widely across different people.

If gut bacterial strains tend to stay within individual hosts, where and when does horizontal gene transfer occur? How do these adaptive genes move between people and eventually become common across entire populations?

The researchers do not yet have a definitive answer, but future studies may explore environmental reservoirs, shared food systems, or other pathways that allow bacterial genes to circulate at a population level.

Why This Matters for Human Health

These findings add a new dimension to how scientists think about diet and health. It is already well established that diet influences which microbes live in the gut. This study shows that diet also shapes which genes those microbes carry, potentially affecting metabolism, digestion, and long-term health outcomes.

The rapid evolution of gut bacteria suggests that ultra-processed foods may be exerting strong and ongoing evolutionary pressure on the microbiome. While the health consequences of these changes are not yet fully understood, they raise important questions about how modern diets may be reshaping our internal ecosystems in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Understanding the Gut Microbiome Beyond This Study

The human gut microbiome is made up of trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. These microbes play essential roles in breaking down food, producing vitamins, regulating the immune system, and even influencing brain function.

Microbes evolve far faster than humans, and their ability to exchange genes makes them especially responsive to environmental changes. This means dietary shifts can have genetic consequences in the microbiome within a single human lifetime.

Studies like this one highlight why the microbiome is increasingly viewed as a dynamic, evolving system rather than a static collection of species.

Looking Ahead

The researchers emphasize that maltodextrin is likely just one example of many dietary components influencing microbial evolution. Other additives, preservatives, and refined ingredients may also be shaping the genetic makeup of gut bacteria in ways that have not yet been identified.

Future research will aim to map these adaptations in more detail, explore their health implications, and better understand how modern lifestyles are influencing microbial evolution on a global scale.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09798-y