Newly Discovered Microbes Are Forcing Scientists to Rethink How Methane Is Produced in Nature

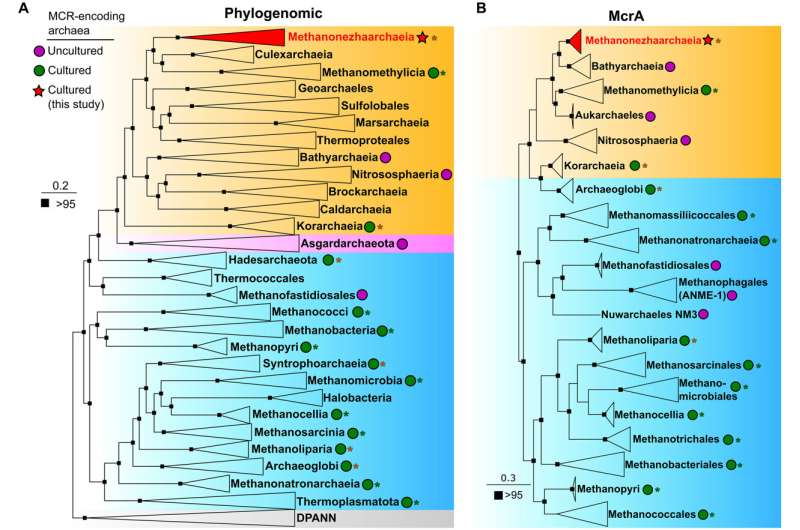

For nearly a century, scientists believed they had a solid grasp on how methane-producing microbes worked. These single-celled organisms, known as methanogens, were thought to follow a fairly narrow biological script: they belonged to one specific group of Archaea and produced methane by converting carbon dioxide under oxygen-free conditions. That assumption has now been seriously shaken.

Recent research led by scientists at Montana State University (MSU) has revealed that methane production in nature is far more complex than previously believed. Newly identified microbes, belonging to an entirely different branch of the tree of life, are producing methane in unexpected ways—challenging long-standing models used to understand greenhouse gas emissions and climate dynamics.

A Break from Nearly 100 Years of Assumptions

Methane-producing microbes were historically believed to exist exclusively within a lineage of Archaea called Euryarchaeota. This idea shaped how scientists modeled methane emissions across ecosystems such as wetlands, rice paddies, landfills, and wastewater treatment plants.

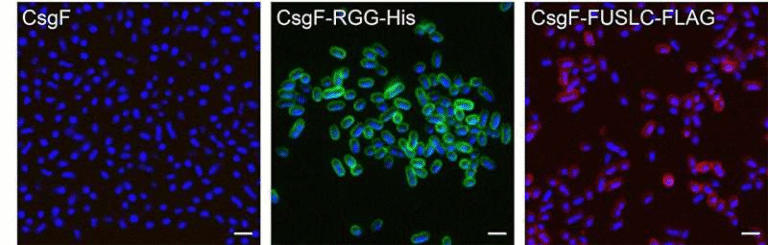

In 2024, researchers working in the laboratory of Roland Hatzenpichler, an associate professor in MSU’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, published the first-ever descriptions of methanogens outside the Euryarchaeota lineage. These newly described organisms belong to another archaeal group known as Thermoproteota.

At the time, the discovery alone was enough to raise eyebrows. But what followed turned out to be even more surprising.

Introducing Methanonezhaarchaeia, a New Class of Methanogens

In December 2025, Hatzenpichler’s team published new findings in Science Advances that focused on a previously unknown group of Thermoproteota methanogens called Methanonezhaarchaeia. This marked the third confirmed class of methane-producing microbes within the Thermoproteota lineage.

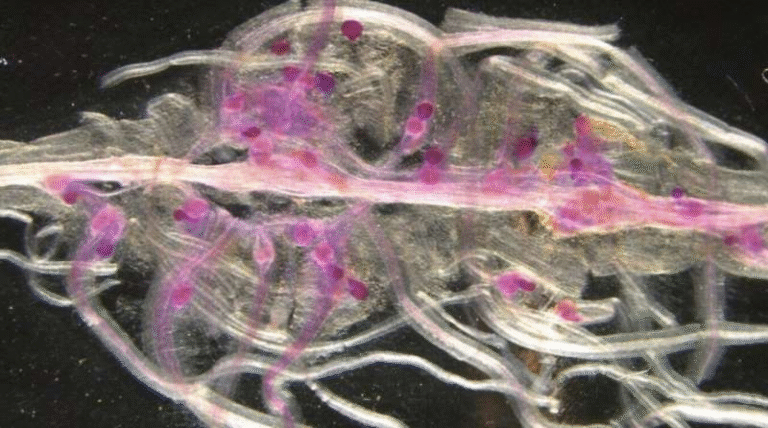

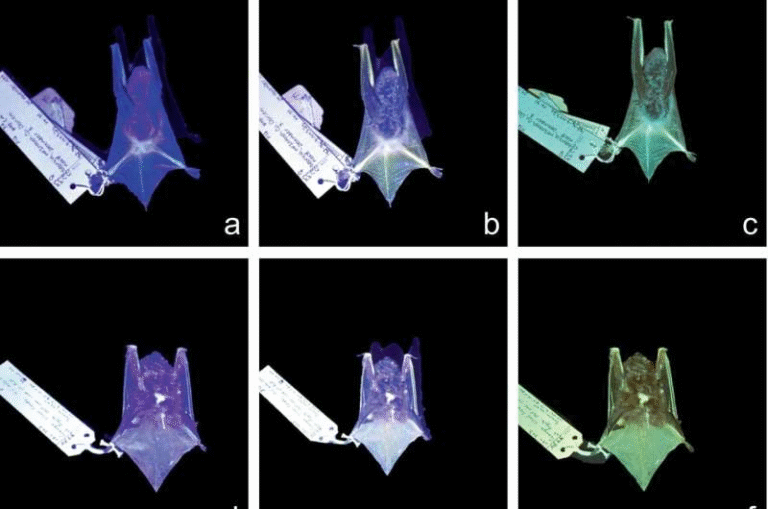

The researchers cultivated these organisms using samples collected from a hot spring in Yellowstone National Park, a location well known for hosting unusual and ancient microbial life. The cultivation work was led by former MSU graduate student Anthony Kohtz and current graduate student Sylvia Nupp.

Based on genomic data alone, scientists initially predicted that Methanonezhaarchaeia would produce methane by converting carbon dioxide (CO₂)—a common pathway seen in classical methanogens. However, when the microbes were grown and tested in the lab, the results told a very different story.

Methane Without Carbon Dioxide

Instead of using carbon dioxide, Methanonezhaarchaeia were found to grow and produce methane by consuming methylated compounds, such as methanol. These compounds are widespread in natural environments and are often produced through the breakdown of organic matter.

This finding aligns with previous discoveries from the same MSU lab, which showed that two other Thermoproteota methanogen groups also rely on methylated compounds rather than CO₂. Together, these results strongly suggest that methyl-based methane production is far more common than scientists once believed, especially among newly identified archaeal lineages.

The discovery highlights a key problem in modern microbial research: genomic predictions do not always reflect real-world biology.

Why This Matters for Climate Science

Methanogens are responsible for producing an estimated 60% of the methane released globally, according to widely cited environmental data. Methane itself is a powerful greenhouse gas, trapping about 28 times more heat than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period.

Because methane plays such a major role in climate change, scientists rely heavily on genomic models to predict where and how much methane is being produced. These models often assume that methane formation is driven primarily by CO₂-based pathways.

The discovery of Thermoproteota methanogens—especially those that use methylated compounds—casts doubt on these assumptions. If large populations of methanogens are producing methane through pathways that models fail to account for, then current estimates of methane sources may be incomplete or inaccurate.

The Limits of Genome-Based Modeling

Genome analysis has become a powerful tool in environmental science, allowing researchers to identify potential metabolic processes without culturing organisms in the lab. However, Hatzenpichler’s research shows that relying solely on genomes can be misleading.

In many ecosystems, scientists measure the concentration of specific compounds and assume that low levels mean those compounds are unimportant. But in reality, those compounds may be scarce precisely because microbes are rapidly consuming them.

The case of Methanonezhaarchaeia demonstrates that experimental validation is essential. Without laboratory cultivation and direct measurement, scientists risk building models on assumptions rather than evidence.

Where These Microbes Live

Although the newly cultivated Methanonezhaarchaeia came from Yellowstone hot springs, Thermoproteota methanogens are not limited to extreme environments.

Research from Hatzenpichler’s lab, including a paper accepted by Current Opinion in Microbiology, shows that these microbes can live in any oxygen-free environment. This includes:

- Wetlands

- Rice paddies

- Landfills

- Oil reservoirs

- Wastewater treatment plants

This broad distribution suggests that Thermoproteota methanogens may play a much larger role in global methane production than previously recognized.

Expanding Research Beyond Hot Springs

While hot springs are useful for studying microbial physiology, they contribute very little to global methane emissions. Recognizing this, Hatzenpichler’s team is expanding its research into ecosystems with far greater climate relevance.

Graduate student Nicole Matos Vega has collected microbial samples from mangrove swamps in Puerto Rico, where unexpectedly high levels of methane production have been observed. She is studying these microbes both in the lab and in their natural environment to ensure that laboratory behavior matches real-world activity.

Another area of focus is wastewater treatment systems. Graduate student Joelie Van Beek has identified Thermoproteota methanogens in the wastewater treatment plant in Bozeman, Montana. The proximity of this facility allows researchers to carefully test environmental variables and better understand how these organisms behave under changing conditions.

What This Means Going Forward

The discovery of Methanonezhaarchaeia and related microbes underscores how much remains unknown about methane production. It also reinforces the idea that microbial diversity has been vastly underestimated, even for processes as well-studied as methanogenesis.

By combining genomic analysis with demanding experimental work, researchers hope to build more accurate models of methane cycling. This approach could ultimately lead to better predictions of greenhouse gas emissions and more informed climate strategies.

As scientists continue to uncover new microbial players and pathways, one thing is clear: the story of methane production is far from finished, and long-held assumptions are finally being put to the test.

Research papers referenced:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aea0936

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.16.682713