A 400-Million-Year-Old Fossil Is Revealing How Plants Evolved the Ability to Grow Into Giants

The tallest plants on Earth today stretch well beyond 100 meters, dominating forests and shaping entire ecosystems. But these giants didn’t appear overnight. They evolved from some of the earliest land plants, many of which were only a few centimeters tall. For decades, scientists have debated how plants made this dramatic leap in size and complexity. Now, a remarkably preserved 400-million-year-old fossil is offering some of the clearest answers yet.

At the center of this discovery is a small, ancient plant called Horneophyton lignieri, found in northern Scotland more than a century ago. Thanks to modern research techniques, this modest fossil is now playing a major role in reshaping what we know about plant evolution, especially the origins of vascular systems that made large plant bodies possible.

A Fossil From Scotland With Big Implications

Horneophyton lignieri was discovered in the early 1900s near the village of Rhynie, in what is now one of the world’s most famous fossil sites: the Rhynie Chert. These fossils date back roughly 407 million years, to the early Devonian period, when plants were just beginning to establish themselves on land.

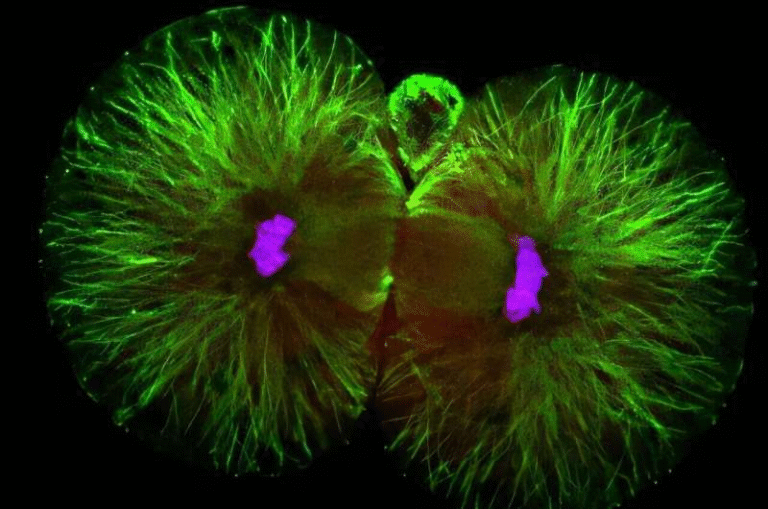

The Rhynie Chert is exceptional because plants, fungi, and small animals preserved there retain cell-level detail. This level of preservation allows scientists to examine internal structures that are normally lost over time, including tissues responsible for transporting water and nutrients.

For many years, researchers believed that Horneophyton already possessed a true vascular system similar to modern plants. However, a new study led by Dr. Paul Kenrick, a fossil plant expert at the Natural History Museum in London, has revealed that this assumption was incorrect.

Challenging Long-Held Ideas About Plant Evolution

Traditionally, scientists thought plant evolution followed a relatively straightforward path:

algae → moss-like plants (bryophytes) → vascular plants, which include ferns, conifers, and flowering plants.

But recent genetic studies have complicated this picture. They suggest that the common ancestor of land plants may not have been a bryophyte or a vascular plant at all. This raised an important question: what did the earliest land plants actually look like on the inside?

Horneophyton may provide the missing piece.

A Vascular System Unlike Anything Alive Today

In modern plants, transport is handled by two specialized tissues:

- Xylem, made of dead cells, carries water and minerals upward from roots to leaves.

- Phloem, made of living cells, distributes sugars and other products of photosynthesis throughout the plant.

This separation allows plants to grow tall and move resources efficiently over long distances.

Horneophyton, however, did things very differently.

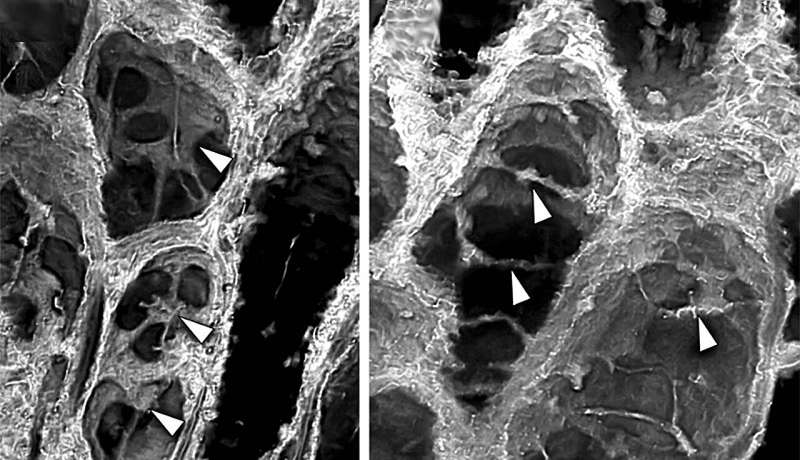

Using confocal laser scanning microscopy, researchers created detailed 3D models of the plant’s internal tissues. These revealed that Horneophyton lacked true xylem and phloem. Instead, it had a novel conducting tissue made largely of transfer cells.

These cells are characterized by distinctive ingrowths of their cell walls, which increase surface area and allow substances to move in and out more efficiently. In Horneophyton, these transfer cells appear to have moved both water and sugars together, rather than in separate channels.

This kind of vascular system has never been observed in any living plant.

Why This Discovery Matters

The discovery suggests that the earliest ancestors of modern plants were more complex than previously believed. Instead of starting with no vascular tissue at all, early land plants may have experimented with hybrid systems before the evolution of separate xylem and phloem.

Importantly, this system would only work in small plants. Transporting water and sugars together over long distances is inefficient, which likely limited Horneophyton’s height to about 20 centimeters.

This helps explain why early plants remained small for so long—and what evolutionary innovations were needed to unlock true plant gigantism.

A Snapshot of Vascular Evolution in Action

Horneophyton represents a possible intermediate stage in vascular evolution. Before it, even simpler plants known as eophytes lived on land around 420 million years ago. These were millimeter-sized organisms with moss-like conducting cells that shared some features with modern phloem.

Shortly after eophytes appeared, plants like Horneophyton evolved more advanced conducting tissues, allowing them to grow larger than their predecessors.

But evolution didn’t stop there.

Another Rhynie Chert plant, Asteroxylon, already had fully separate xylem and phloem. This gave it a major advantage, allowing it to grow roughly twice as tall as Horneophyton. That innovation eventually paved the way for towering trees, dense forests, and the land-based ecosystems we know today.

Ironically, even at 407 million years old, Horneophyton’s vascular system was already something of an evolutionary dead end.

The Rhynie Chert as a Window Into Early Life on Land

The Rhynie Chert continues to be one of the most important fossil sites on Earth. In addition to plants, it preserves early fungi, arthropods, and plant-fungal interactions, offering a rare glimpse into the first complex terrestrial ecosystems.

Many plants from this site appear to have had unique conducting systems that don’t fit neatly into modern categories. According to researchers, these plants were often “shoehorned” into classifications that didn’t fully reflect their biology.

Re-examining them with modern technology is revealing just how experimental early plant evolution really was.

How This Research Changes the Big Picture

This study supports the idea that:

- Phloem-like cells likely evolved before xylem

- Early plants tested multiple transport strategies

- The separation of water and sugar transport was a key step toward large plant size

- The common ancestor of land plants was likely structurally complex, not simple

As researchers continue to analyze Rhynie Chert fossils, they expect to uncover even more evidence of how plants transformed Earth—reshaping the atmosphere, stabilizing soils, and making complex land life possible.

Why Plant Vascular Systems Matter Beyond Fossils

Understanding how vascular systems evolved isn’t just about ancient history. These systems underpin modern agriculture, forestry, and climate science. The ability of plants to move water efficiently affects:

- Carbon storage

- Climate regulation

- Crop productivity

- Forest resilience

By studying how these systems originated, scientists gain insight into the fundamental rules that still govern plant life today.

Research Reference

Paul Kenrick et al. (2025). “Transfer cells in Horneophyton lignieri illuminate the origin of vascular tissues in land plants.” New Phytologist.

https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.70850