Targeting Bacterial Decision-Making Could Open a New Path to Outsmart Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotic resistance has quietly become one of the most serious global health threats of our time. Infections that were once easily treated are now harder to control, and many routine medical procedures depend on antibiotics that are steadily losing their effectiveness. Against this backdrop, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have uncovered a promising new strategy: instead of killing bacteria outright, they aim to interfere with how bacteria make decisions.

This research, published in Nature Communications, focuses on understanding and manipulating bacterial behavior. The idea is simple but powerful. Traditional antibiotics work by killing bacteria or stopping their growth, but this often leaves behind a small group of survivors. These survivors multiply, and over time they become resistant. By contrast, altering bacterial behavior could weaken infections without triggering the same evolutionary arms race.

Why Killing Bacteria Isn’t Always the Best Strategy

Most antibiotics work in a blunt way: they kill bacteria. While effective in the short term, this approach has a major downside. When antibiotics are applied, not every bacterial cell dies. The ones that survive are often the most resilient, and they repopulate quickly. Over time, entire bacterial populations can become resistant.

Researchers involved in this study argue that this process mirrors what happens in cancer treatment, where resistant cells survive chemotherapy and cause relapse. The team believes that reducing bacterial virulence rather than eliminating bacteria outright may offer a better long-term solution.

Bacteria Are More Sophisticated Than We Think

Despite their microscopic size, bacteria are far from simple organisms. They can communicate, respond to environmental changes, and make strategic decisions that improve their chances of survival. One of their most effective survival strategies is forming biofilms.

Biofilms are dense, sticky communities of bacteria that attach to surfaces and protect the cells inside. Within a biofilm, bacteria are harder to kill, more resistant to antibiotics, and better able to evade the immune system. Biofilms play a major role in persistent infections and are notoriously difficult to treat.

The Carnegie Mellon team wanted to understand whether it was possible to shift bacterial behavior away from forming biofilms and toward a weaker, less infectious state.

Studying Vibrio cholerae and Biofilm Control

The researchers focused on Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium responsible for cholera. Cholera remains a serious problem in parts of the world without access to clean drinking water, and V. cholerae is also a well-established model organism for studying bacterial infection and behavior.

Graduate student Emmy Nguyen and assistant professor Drew Bridges identified a specific regulatory pathway that controls biofilm formation in V. cholerae. This pathway doesn’t just affect biofilms—it also influences metabolism, movement, stress responses, and other critical bacterial functions.

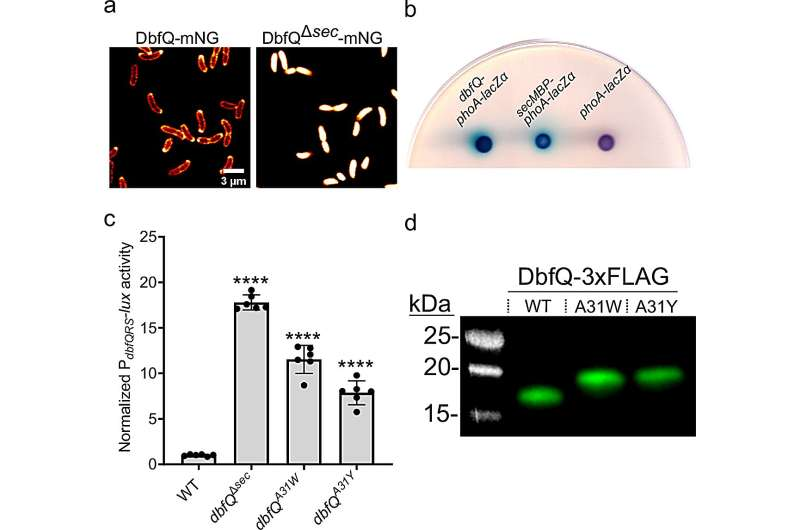

At the heart of this system is a two-component regulatory pathway known as DbfRS, along with a small protein called DbfQ. Together, these components help bacteria decide whether to prioritize growth or protection when facing stressful or hostile environments.

The Role of DbfQ and the DbfRS System

The researchers discovered that DbfQ, a small protein located in the periplasmic space of the bacterial cell, plays a key role in regulating the activity of the DbfRS system. When DbfQ is secreted into the periplasm, it alters how DbfRS functions, effectively nudging the bacteria toward a defensive, less aggressive state.

When this pathway is activated, bacteria reduce biofilm formation and shift their priorities. Instead of focusing on rapid growth and colonization, they invest more energy in stress defenses and survival. This makes them less capable of causing infection.

Importantly, this change doesn’t kill the bacteria. It simply makes them weaker and less harmful.

Testing the Pathway in Infection Models

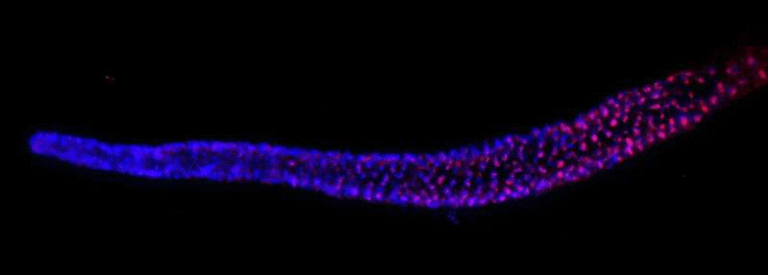

To understand whether this pathway actually affects infection, the researchers collaborated with scientists at the University of Pittsburgh and Tufts University School of Medicine. They compared normal V. cholerae bacteria with mutant strains in which the pathway was constantly activated.

When these strains were used to infect mice, the results were striking. The mutant bacteria struggled to grow and colonize the host. This provided strong evidence that forcing bacteria into this altered behavioral state can reduce their ability to cause disease.

A Discovery With Broad Implications

One of the most encouraging findings came from a bioinformatic analysis led by M. R. Pratyush, a graduate student working with Associate Professor N. Luisa Hiller. The analysis revealed that the protein module controlling biofilm behavior in V. cholerae is found in many other bacterial species.

This suggests that the mechanism uncovered in this study may not be unique to cholera bacteria. Instead, it could represent a shared strategy across diverse bacterial pathogens, opening the door to treatments that work against multiple infections.

From Basic Science to Future Therapies

The researchers emphasize that this work began as basic science—an effort to understand how bacteria function at a fundamental level. But the implications are clearly translational.

The next step is to identify small molecules that can deliberately activate this pathway in harmful bacteria. Such molecules could be used alone or in combination with existing antibiotics to weaken infections and make them easier to clear.

Rather than replacing antibiotics, this approach could extend the usefulness of current drugs by reducing the likelihood that resistance will emerge.

Understanding Biofilms and Their Role in Disease

Biofilms are central to many chronic infections, including those associated with medical devices like catheters and implants. Within biofilms, bacteria are protected by a matrix that blocks antibiotics and shields them from immune cells.

By targeting the regulatory systems that control biofilm formation, scientists hope to disrupt these communities before they become established. This could lead to better outcomes for patients and fewer treatment failures.

Why This Research Matters

Antibiotic resistance is not a future problem—it is already here. The World Health Organization has repeatedly warned that without new strategies, we risk entering a post-antibiotic era where common infections become deadly again.

This research offers a fresh perspective. Instead of fighting bacteria head-on, it suggests that we can outsmart them by interfering with the decisions they make. By shifting bacteria into a weakened, less infectious state, we may be able to reduce disease without accelerating resistance.

Looking Ahead

The Carnegie Mellon team plans to continue exploring how this pathway works and how it can be manipulated. Their long-term goal is to translate these findings into real-world treatments that work differently from traditional antibiotics.

As antibiotic resistance continues to rise, approaches like this—focused on behavioral control rather than outright destruction—may play a critical role in protecting global health.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66735-3