Ant Societies Grew Powerful by Becoming More Squishable According to a New Evolutionary Study

Ants are tiny, but their societies can be astonishingly vast. Some colonies contain millions of individuals working together with incredible coordination. A new scientific study now explains one of the key evolutionary strategies that made this possible: many ants succeeded not by becoming tougher as individuals, but by becoming cheaper, weaker, and more numerous.

Research published in Science Advances by scientists from the University of Maryland and the University of Cambridge reveals that ant evolution has been shaped by a fundamental tradeoff between individual protection and collective power. The researchers describe this idea with a memorable term—the evolution of squishability—to capture how reduced investment in individual armor helped ants build larger and more complex societies.

Quantity Versus Quality in Evolution

The study draws inspiration from a familiar thought experiment: would you rather face one massive opponent or many smaller ones? In biology, this same question plays out across evolutionary timescales. For ants, the answer appears to be clear—more individuals can outweigh stronger individuals.

Ant workers are protected by a hard outer layer called the cuticle, which functions as both armor and structural support. The cuticle protects ants from predators, dehydration, disease, and physical damage. However, it is also nutritionally expensive to build, requiring large amounts of nitrogen and minerals, which are often scarce in nature.

The researchers found that many ant species evolved to invest less in this protective cuticle. By reducing how much armor each worker has, colonies were able to redirect resources toward producing more workers, increasing overall colony size and effectiveness.

How the Study Was Conducted

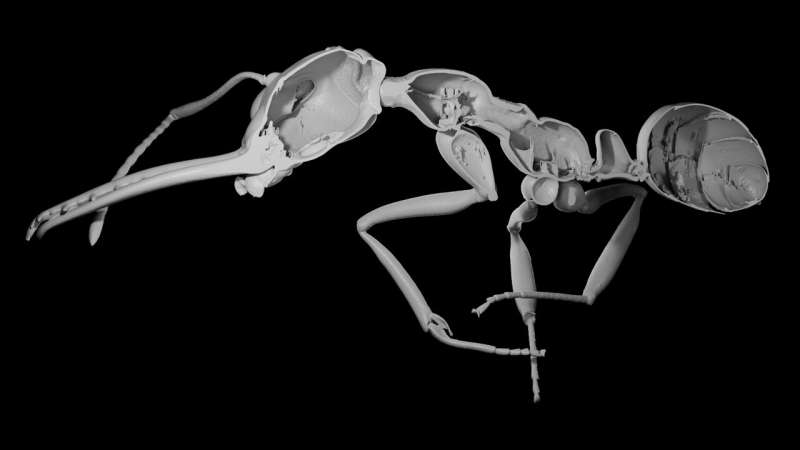

To test this idea, the research team analyzed an unusually large and detailed dataset. Using 3D X-ray microtomography, they examined the internal and external anatomy of ant workers from more than 500 species. This technique allowed the scientists to precisely measure:

- Total body volume

- Cuticle volume

- The proportion of the body devoted to protective armor

The results showed striking variation. In some species, the cuticle made up as little as 6% of total body volume, while in others it accounted for as much as 35%. These anatomical measurements were then combined with evolutionary models and data on colony size to see how these traits changed over time.

The pattern was consistent: species with lower cuticle investment tended to have much larger colonies.

Why Thinner Armor Can Be an Advantage

At first glance, thinner armor sounds like a bad deal. Less protection means individual ants are more vulnerable to injury or death. But in a highly social species, the fate of any one worker matters less than the success of the colony as a whole.

The researchers argue that once colonies reach a certain size, collective defenses begin to replace individual defenses. These include:

- Group nest defense, where many workers can repel predators

- Collective foraging, which reduces individual risk

- Disease control behaviors, such as grooming and waste management

- Division of labor, allowing workers to specialize

In this context, investing heavily in individual armor becomes less necessary. The colony itself acts as a protective system, allowing ants to survive and thrive even if individual workers are relatively fragile.

Larger Colonies and Faster Evolution

One of the most intriguing findings of the study is the link between reduced cuticle investment and higher diversification rates. Diversification refers to how quickly new species evolve over time, and it is often used as a measure of evolutionary success.

The researchers found that ant lineages with thinner cuticles tended to speciate more rapidly, giving rise to a greater diversity of species. This is notable because relatively few traits have been clearly linked to diversification in ants.

While the exact mechanism is not fully understood, one hypothesis is that ants with lower nutritional requirements are better able to colonize nutrient-poor environments. Needing less nitrogen to build their bodies may allow them to spread into new habitats that other species cannot exploit.

Ants as a Model for Social Evolution

Ants are particularly well suited for studying how complex societies evolve. Their colonies range from just a few individuals to supercolonies with millions of workers. This wide variation provides a natural laboratory for examining how biological tradeoffs shape social organization.

The study also highlights a broader principle seen throughout biology: as societies become more complex, individuals often become simpler. Tasks that a solitary organism would need to perform alone can instead be distributed across a group.

This pattern mirrors the evolution of multicellularity, where individual cells give up autonomy but contribute to a larger, more capable organism. In both cases, cooperation allows for greater complexity and success, even if it comes at the cost of individual robustness.

The Idea of “Cheaper” Individuals

The researchers use the term cheaper workers to describe ants that require fewer resources to produce. Being cheaper does not mean being less important—it means being easier to replace and more efficient at the colony level.

This concept challenges the assumption that evolution always favors stronger or better-protected individuals. Instead, it shows that efficiency and numbers can be just as powerful, especially in social organisms.

The idea of squishability is not meant to trivialize ants, but to emphasize that reduced individual durability can be a successful evolutionary strategy when paired with cooperation.

Parallels With Human Systems

The study also invites comparisons beyond biology. Similar quantity-versus-quality tradeoffs appear in human history, economics, and warfare. For example:

- Heavily armored knights were eventually outmatched by large armies of less-protected soldiers with specialized roles

- Industrial systems often favor many simple components over a few complex ones

- Military theorists have long studied how numerical superiority can outweigh individual strength

These parallels underscore how universal this tradeoff is, appearing again and again in both natural and human-designed systems.

Could Other Social Insects Follow the Same Path?

While this study focuses on ants, the authors suggest that other social insects—such as termites—may have followed similar evolutionary routes. However, this has not yet been tested at the same scale.

If confirmed, it would strengthen the idea that reducing individual investment is a common pathway toward large, successful societies in nature.

Why This Study Matters

This research provides one of the clearest examples of how internal resource allocation can shape the evolution of entire lineages. It helps explain why ants are among the most ecologically dominant animals on Earth, despite their small size and apparent fragility.

By showing that weaker individuals can lead to stronger societies, the study reshapes how we think about success in evolution. Sometimes, being more squishable is exactly what makes a species unstoppable.

Research paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adx8068