How the Brain Uses Space and Brain Waves to Organize Thought More Flexibly

The human brain performs a remarkable balancing act every second of the day. Our thoughts are guided by existing knowledge, goals, and plans, yet we can also react quickly and flexibly to new information. How this controlled yet adaptable form of thinking emerges from billions of neurons has long been one of neuroscience’s biggest questions. A new study from researchers at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT offers compelling evidence that the answer may lie in how the brain uses space itself as a computational resource.

The research supports a framework known as Spatial Computing, a theory that explains how the brain dynamically organizes neurons into functional groups to handle different cognitive tasks. Rather than relying on fixed circuits for every type of thinking, the brain appears to use brain waves to flexibly recruit and coordinate neurons as needed. The findings were published in the journal Current Biology and are based on detailed measurements of neural activity in animals performing memory and categorization tasks.

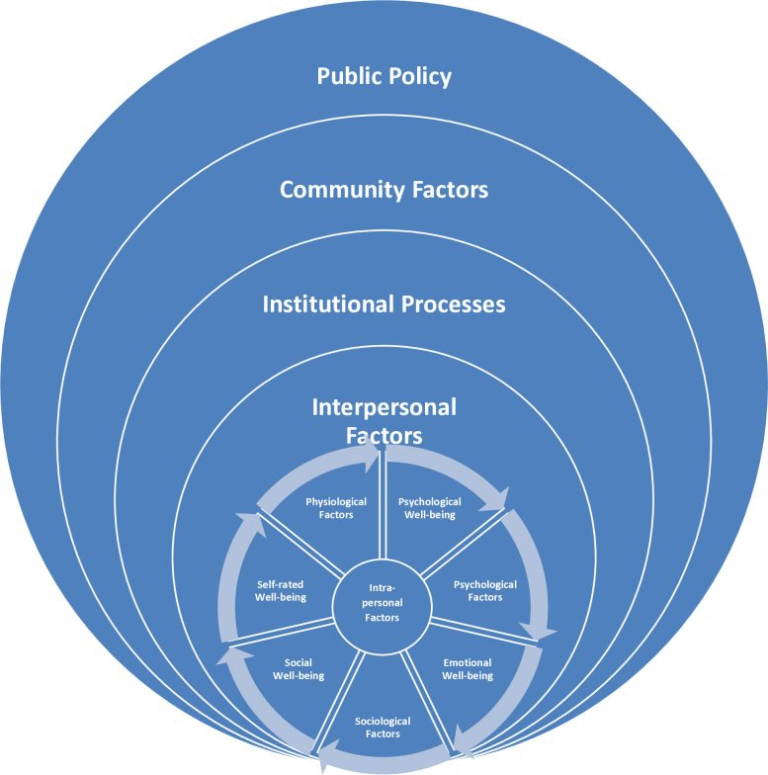

The Core Idea Behind Spatial Computing

Spatial Computing was first proposed in 2023 by Earl K. Miller, a Picower Professor at MIT, along with colleagues Mikael Lundqvist and Pawel Herman. The theory focuses on the prefrontal cortex, a brain region heavily involved in planning, decision-making, and working memory.

The central idea is straightforward but powerful: instead of permanently wiring neurons into task-specific circuits, the brain uses alpha and beta frequency brain waves—roughly in the 10 to 30 hertz range—to impose temporary patterns of control over specific physical patches of cortex. These waves act like organizational signals, telling neurons when to become active, when to stay quiet, and how to coordinate with one another.

In this framework, neurons can participate in multiple tasks over time because they are not locked into one rigid role. Years of prior experiments have already shown that many neurons in the prefrontal cortex are active across different tasks. Spatial Computing provides a mechanism for how this flexibility is possible without constant rewiring.

Brain Waves as Control Signals, Not Information Carriers

A key distinction in the theory is between what carries information and what controls information flow. According to Spatial Computing, the spiking activity of neurons carries sensory and content-specific information, such as the identity of a shape or color. In contrast, alpha and beta waves carry the rules, structure, and control signals that govern how that information is processed.

One way to think about these waves is as stencils. They shape where and when neurons can take in information from the senses or express that information downstream. In this sense, the waves represent the “rules of the task,” while the spikes represent the data being worked on.

Putting the Theory to the Test

To move Spatial Computing from theory to evidence, the research team, led by Zhen Chen, designed experiments to test five specific predictions derived from the framework. They recorded both brain waves and individual neural spikes from the prefrontal cortex using four implanted electrode arrays while animals performed two working memory tasks and one categorization task.

These tasks were structured to clearly separate sensory information from task rules. For example, animals might see a sequence such as a blue square followed by a green triangle and then be required to determine whether a new sequence matched the earlier one, either in identity, order, or both.

Prediction One and Two: Separating Rules From Sensory Content

The first two predictions focused on the division of labor between waves and spikes. If Spatial Computing is correct, alpha and beta waves should encode task rules, while neural spikes should encode sensory inputs.

The data strongly supported this. Sensory information was present in the spiking activity of neurons but not in the alpha or beta waves. At the same time, both spikes and waves carried some task-related information, but the signal was much stronger in the brain waves, especially at moments when rules were most relevant to performing the task.

Task Difficulty Strengthens Control Signals

The categorization task offered an additional test. The researchers deliberately varied the level of abstraction, making some versions of the task more cognitively demanding than others. As task difficulty increased, alpha and beta wave power also increased. This finding further supports the idea that these waves are responsible for enforcing task rules rather than encoding sensory details.

Prediction Three and Four: Space Matters

Spatial Computing also predicts that alpha and beta waves should be spatially organized across the cortex. The researchers observed exactly that. Under the electrode arrays, there were distinct patches where wave power was higher or lower.

Crucially, where alpha and beta power was strong, sensory spiking activity was suppressed. Where wave power was weak, spiking activity increased. This inverse relationship shows how brain waves can selectively gate information, turning certain cortical regions “on” or “off” depending on task demands.

Prediction Five: Signals Predict Performance

The final prediction was perhaps the most telling. If Spatial Computing truly governs cognition, then trial-by-trial variations in wave power and timing should correlate with behavioral performance. The results confirmed this as well.

Alpha and beta wave patterns differed significantly between correct and incorrect trials. Even more interestingly, these signals could predict the type of mistake the animals made. Errors related to misapplying task rules, such as mixing up the order of stimuli, were linked to differences in alpha and beta activity. Errors related to identifying the stimuli themselves were not.

How This Fits With Human Brain Research

Although these experiments were conducted in animals, the findings align well with existing human studies. Research using EEG and MEG has shown that alpha oscillations in humans help suppress activity in task-irrelevant brain regions and play a role in top-down control during complex tasks. Other studies have found that alpha rhythms help govern task-related activity in the prefrontal cortex, echoing the mechanisms proposed by Spatial Computing.

Why This Matters for Understanding Cognition

At its core, this research reframes cognition as a process of large-scale neural self-organization. Instead of relying solely on fixed anatomical circuits, the brain appears to use rhythmic signals to flexibly organize itself in space. This helps explain how we can rapidly switch tasks, apply abstract rules, and reuse the same neurons for different purposes without losing stability.

The researchers also note that brain waves often travel across the cortex, rather than remaining stationary. Accounting for this dynamic movement will be an important next step in refining Spatial Computing.

The Bigger Picture of Brain Waves and Thinking

Beyond this specific study, brain oscillations have long been linked to attention, memory, and perception. Alpha waves are often associated with inhibition and focus, while beta waves are linked to maintaining cognitive states. Spatial Computing brings these ideas together by showing how oscillations can act as a computational dimension, shaping how thought itself unfolds across the brain.