New Antiviral Drugs for Herpesviruses Reveal Exactly How They Shut Down Viral Replication

Scientists have taken an important step forward in the fight against herpesviruses by uncovering how a promising new class of antiviral drugs actually works at the molecular level. Researchers from Harvard Medical School have revealed, in remarkable detail, how these drugs disable a critical viral enzyme, offering new hope for patients who suffer from drug-resistant herpes infections, especially those with weakened immune systems.

This research focuses on herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), a virus best known for causing cold sores but also capable of triggering serious and even life-threatening disease, including brain infections. The findings are particularly significant because existing antiviral treatments are increasingly failing against resistant strains of the virus.

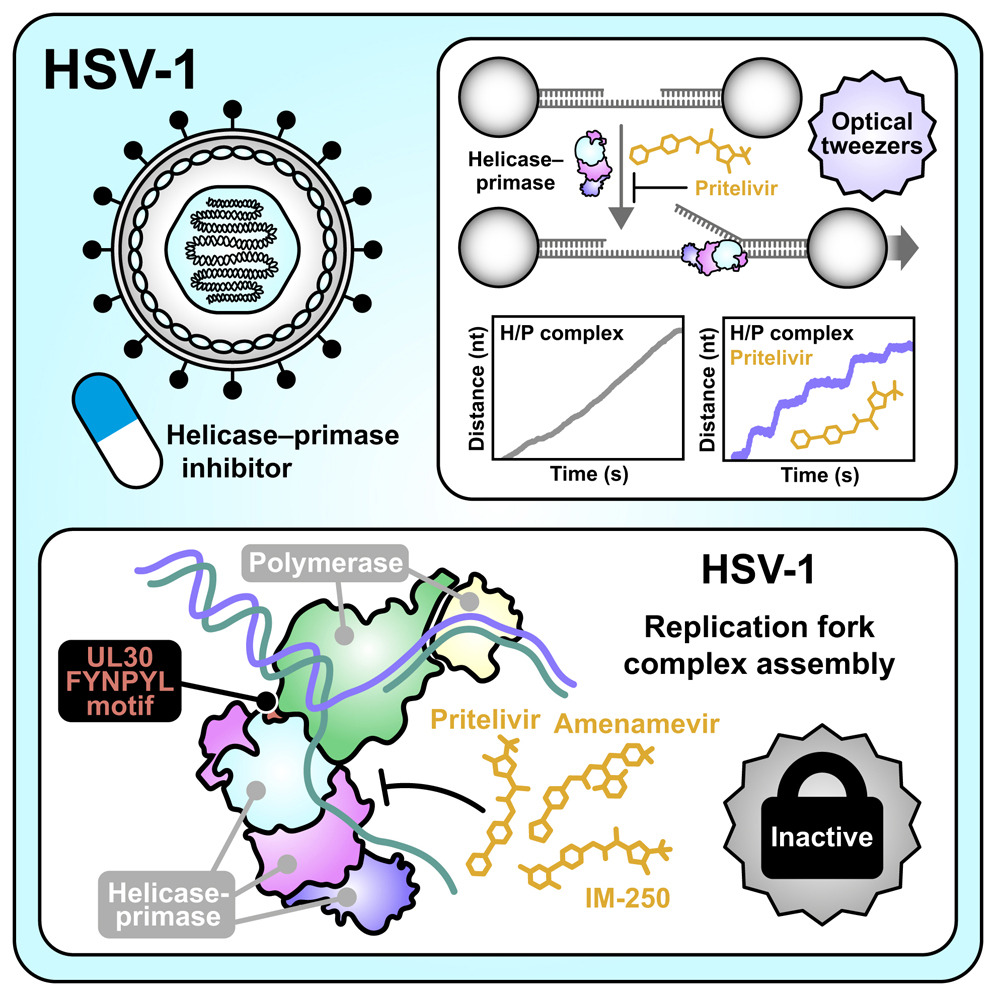

The study, published in the journal Cell, provides long-sought answers about how a new group of antiviral drugs called helicase-primase inhibitors, or HPIs, block herpesvirus replication.

Understanding the clinical problem of drug-resistant herpes

Herpesviruses are a large family of DNA viruses responsible for several well-known illnesses, including chickenpox, shingles, and mononucleosis. One of their defining traits is their ability to remain latent for life, reactivating periodically under certain conditions. HSV-1, while common, can become extremely dangerous in people with compromised immune systems, such as cancer patients, transplant recipients, or individuals on long-term immunosuppressive therapy.

Most FDA-approved antiviral drugs for HSV-1 target the virus’s DNA polymerase, the enzyme that copies the viral genome. While these medications are often effective, the virus can evolve resistance when exposed repeatedly to the same drug class. In clinical settings, this resistance leaves physicians with very limited treatment options.

The researchers behind the new study are well aware of this problem. One of the study’s co-senior authors, Jonathan Abraham, is both an infectious disease physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a microbiology researcher at Harvard Medical School. His dual role allowed him to see firsthand how devastating drug-resistant HSV infections can be for immunocompromised patients, even when their primary illness, such as cancer, is successfully treated.

A new class of antivirals enters the picture

In response to growing resistance, scientists have been developing helicase-primase inhibitors, a newer class of antiviral drugs that target a different part of the viral replication machinery. Some of these drugs are currently being tested in U.S. clinical trials, and at least one has already been approved in Japan. Despite their promise, researchers until now did not fully understand how these drugs worked.

That knowledge gap is what this study set out to fill.

Abraham teamed up with Joseph Loparo, a professor of biological chemistry and molecular pharmacology at Harvard Medical School, to explore the biophysical mechanisms behind HPI drugs. By combining expertise in structural biology and real-time molecular imaging, the team aimed to see not just where the drugs bind, but how that binding actually stops the virus from replicating.

The critical role of the helicase-primase enzyme

To understand why HPIs are so powerful, it helps to know what the helicase-primase complex does. This enzyme plays a central role in herpesvirus DNA replication.

The helicase acts like a molecular motor. It moves along the viral DNA, unwinding the double helix and separating it into single strands. This unwinding step is essential because the DNA polymerase cannot copy double-stranded DNA directly.

The primase, on the other hand, creates a short RNA primer. This primer serves as a starting point that allows the DNA polymerase to begin building a new DNA strand, much like the initial teeth of a zipper that allow the slider to engage.

By interfering with this enzyme complex, HPIs effectively shut down the replication process before it can even get going.

Seeing the virus at near-atomic resolution

One of the biggest challenges in studying the helicase-primase complex is that it is highly flexible and constantly changing shape. Until now, this “wiggliness” made it extremely difficult to capture clear structural images of the enzyme.

The breakthrough came from using the inhibitors themselves. When an HPI binds to the helicase-primase, it locks the enzyme into a stable shape, making it possible to visualize.

Using cryogenic electron microscopy, or cryo-EM, the researchers captured near-atomic-resolution images of the HSV-1 helicase-primase bound to several different inhibitors. These images revealed exactly where and how the drugs attach to the enzyme and prevent it from functioning.

The team also used cryo-EM to visualize how the helicase-primase interacts with the viral DNA polymerase during replication. This larger structure, known as the replication fork complex, may help scientists identify new drug-binding sites that could be targeted in future antiviral therapies.

All cryo-EM data for the study were collected at the Harvard Cryo-EM Center for Structural Biology, highlighting the role of advanced research infrastructure in enabling these discoveries.

From static snapshots to real-time action

While cryo-EM provides incredibly detailed snapshots, the researchers wanted to understand how the inhibition process unfolds in real time. To do this, they turned to a powerful technique known as optical tweezers.

Optical tweezers use highly focused laser beams to manipulate microscopic objects using the momentum of photons. In this study, the team used the tweezers to suspend a strand of viral DNA, along with the helicase-primase enzyme, between two tiny beads.

By watching the system under the microscope, the researchers could observe individual helicase molecules unwinding DNA. When they introduced tiny amounts of an HPI drug, they saw the helicase motor stall and stop, providing direct evidence of how the inhibitor gums up the enzyme’s mechanical action.

This ability to watch viral machinery fail in real time offered a deeper understanding of the drug’s effectiveness and confirmed what the structural images suggested.

Why these findings matter for future antiviral development

This study represents the first time scientists have successfully revealed the structure of herpesvirus enzymes like the helicase-primase in such detail. More importantly, it explains why helicase-primase inhibitors work so well, especially against drug-resistant strains of HSV.

By understanding the precise physical and chemical interactions between the drugs and the viral proteins, researchers can now design more effective and more specific antivirals. The insights may also extend beyond herpesviruses to other DNA viruses that rely on similar replication machinery.

For clinicians, these findings offer hope that patients who currently have limited treatment options may soon benefit from new antiviral therapies that are both powerful and resistant to the resistance problem itself.

Additional context on herpesvirus treatment challenges

Despite decades of antiviral research, herpesviruses remain difficult to eliminate completely due to their lifelong latency. Current treatments manage symptoms and reduce viral replication but do not cure the infection. The emergence of resistance has made this situation even more challenging.

Helicase-primase inhibitors represent a strategic shift in antiviral design. Instead of targeting the same viral enzyme repeatedly, these drugs attack a different, equally essential part of the viral life cycle. This approach reduces cross-resistance and opens the door to combination therapies that could further suppress viral replication.

As imaging and structural biology tools continue to advance, studies like this demonstrate how seeing molecular processes directly can transform drug development and lead to more rational, targeted treatments.

Research paper reference:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.11.041