B Cells Can Temporarily Revert to a Stem-Like State, Potentially Raising the Risk of Lymphoma

Immune cells known as B cells play a central role in protecting the body. Their primary job is to produce antibodies that recognize and neutralize invading bacteria, viruses, and other harmful substances. For decades, scientists believed that once B cells reached full maturity, their identity and function were essentially locked in. A new study from Weill Cornell Medicine, however, challenges that assumption and reveals a surprising and potentially risky twist in B-cell biology.

According to this research, mature B cells can temporarily regain stem-cell-like flexibility during an immune response. While this flexibility helps the immune system fine-tune antibody production, it may also create conditions that allow lymphomas—cancers of the lymphatic system—to develop from mature B cells rather than from stem cells, as is more typical in many other cancers.

How B Cells Normally Develop and Specialize

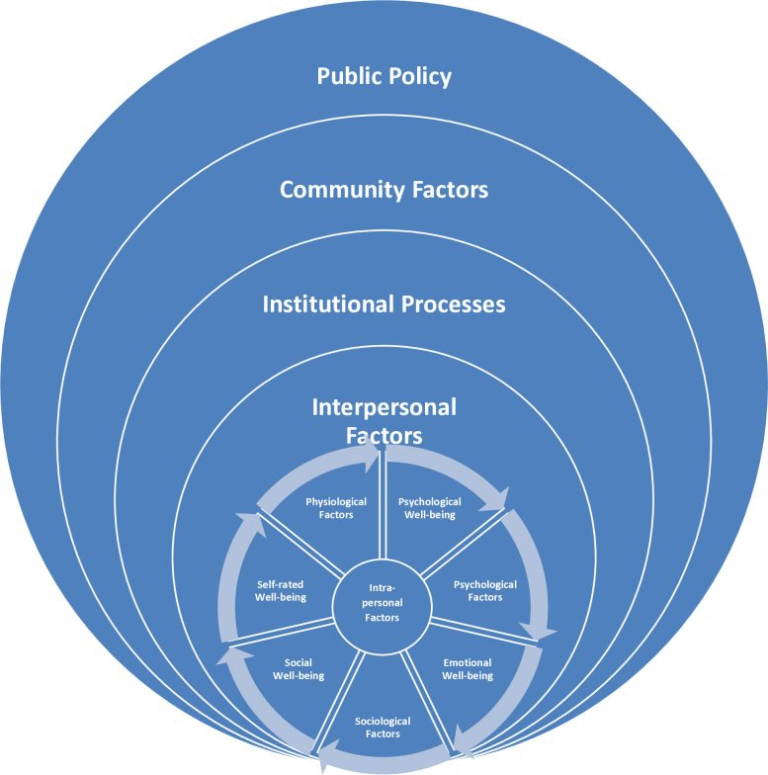

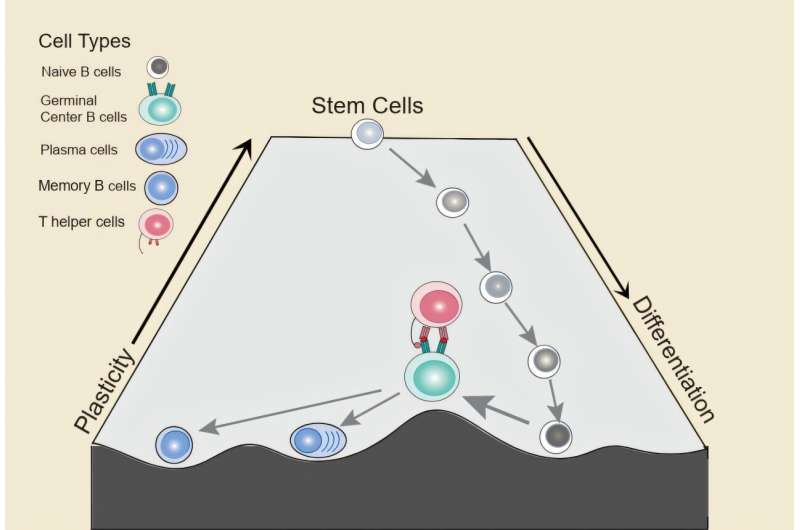

In general, cells in the body follow a one-way path. They begin as stem cells with broad potential and gradually become more specialized. As this happens, they lose plasticity, meaning they lose the ability to transform into other cell types. Mature B cells are considered terminally differentiated, meaning their fate should be fixed.

But the immune system is not a static system. When B cells encounter a foreign molecule, known as an antigen, they enter an intense training phase inside structures in the lymph nodes called germinal centers. This is where the immune system refines its antibody response.

Inside the Germinal Center Reaction

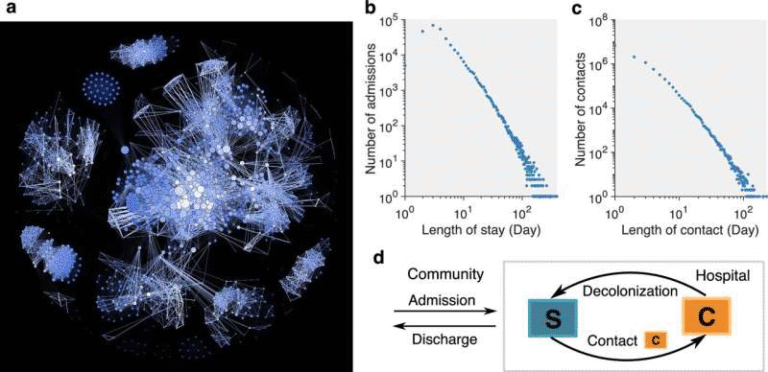

The germinal center reaction is a highly dynamic process. Within the germinal center, B cells move back and forth between two distinct zones:

- In the dark zone, B cells divide rapidly and intentionally mutate their antibody genes. This creates a diverse pool of antibodies with slightly different properties.

- In the light zone, these B cells stop dividing and compete for signals from helper T cells. Only those that produce the most effective antibodies receive survival signals.

B cells that succeed in this competition will either become plasma cells, which produce large amounts of antibodies, or memory B cells, which help the immune system respond more quickly if the same antigen appears again. Cells that fail are eliminated through programmed cell death, also known as apoptosis.

This rapid cycling between growth, mutation, selection, and death is already unusual for mature cells. What the new study uncovered is even more unexpected.

A Temporary Return to Stem-Like Plasticity

The researchers found that during the germinal center reaction, a subset of mature B cells temporarily reactivates genetic programs normally associated with stem cells and progenitor cells. In other words, these B cells briefly loosen their specialized identity and regain a level of flexibility usually seen only in early developmental stages.

This plasticity is transient. Under normal conditions, it is quickly shut down as B cells commit to becoming plasma cells or memory B cells. However, while it lasts, the cells are in a more vulnerable and adaptable state.

Crucially, these changes are epigenetic, not genetic. That means the DNA sequence itself is not altered. Instead, the way DNA is packaged and accessed inside the cell changes, allowing different genes to be turned on or off temporarily. This makes the process reversible, but also potentially exploitable.

The Role of Helper T Cells

Not all germinal center B cells regain this flexibility. The study showed that only a specific subset of B cells that receive help from follicular helper T cells enter this highly plastic state. These T cells provide signals that weaken B-cell identity and activate stem-like programs.

When researchers experimentally increased or decreased communication between B cells and T cells, they could directly enhance or suppress B-cell plasticity. This confirmed that the process is tightly regulated and not a random accident of cell division.

Single-cell analyses revealed that B cells receiving T-cell help showed reduced expression of genes that define them as B cells, alongside increased activity of genes linked to stemness and early development.

Chromatin, Histone H1, and Multiple Routes to Plasticity

The study also examined the role of chromatin, the structure that packages DNA inside cells. A protein called histone H1 helps keep chromatin tightly packed and limits access to certain genes. Histone H1 is frequently mutated in lymphoma patients.

When the researchers removed histone H1 in germinal center B cells, the chromatin became more open, and plasticity increased across all germinal center B cells, even those that were not receiving T-cell help. This finding suggests there may be multiple pathways leading to the same flexible state.

In normal immune responses, these pathways are carefully controlled. But if mutations disrupt this control, the balance can shift.

Connecting Plasticity to Lymphoma Risk

Most lymphomas are driven by genetic mutations, but this study suggests that mutations may take advantage of a naturally occurring window of epigenetic flexibility. The researchers found that gene expression signatures associated with this highly plastic B-cell state were strongly upregulated in many lymphoma patients.

Even more concerning, these signatures were linked to worse clinical outcomes, indicating that increased or prolonged plasticity may give cancer cells a growth or survival advantage.

This helps explain a long-standing puzzle in cancer biology: why many lymphomas originate from mature B cells, rather than from stem cells. The answer may be that mature B cells briefly behave like stem cells at exactly the wrong moment.

Why This Matters for Treatment and Diagnosis

Understanding germinal center B-cell plasticity opens new possibilities for cancer research. If scientists can identify the molecules and pathways that control this temporary stem-like state, they may be able to:

- Develop biomarkers that predict lymphoma risk or prognosis

- Identify patients more likely to respond to specific therapies

- Design treatments that specifically target abnormal plasticity without disrupting normal immune function

Rather than viewing plasticity as purely dangerous, the study emphasizes that it is a normal and necessary feature of healthy immune responses. Problems arise only when this process is hijacked or prolonged by mutations.

Broader Context: Plasticity in Biology and Cancer

Cellular plasticity is increasingly recognized as a double-edged sword. In development and tissue repair, it provides flexibility and resilience. In cancer, the same flexibility can allow cells to adapt, resist treatment, and spread.

This research adds B cells to a growing list of cell types where temporary identity changes play a key role in both normal biology and disease. It also highlights how epigenetic regulation, rather than DNA mutations alone, can shape cancer risk.

Final Thoughts

The discovery that mature B cells can briefly unlock a stem-like state reshapes how scientists think about immune responses and lymphoma development. What appears to be a finely tuned feature of immune defense may also represent a moment of vulnerability, where the seeds of cancer can take hold.

By mapping this process in detail, the researchers have provided a clearer picture of how normal immune function and cancer biology intersect—and where future therapies might intervene.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-025-01833-4