A 4,000-Year-Old Sheep May Have Finally Explained How the Bronze Age Plague Spread Across Eurasia

For decades, scientists have puzzled over a simple but stubborn question: how did the Bronze Age plague manage to spread across vast parts of Eurasia without the help of fleas? A new discovery suggests the answer may have been grazing quietly alongside ancient humans all along — a domesticated sheep.

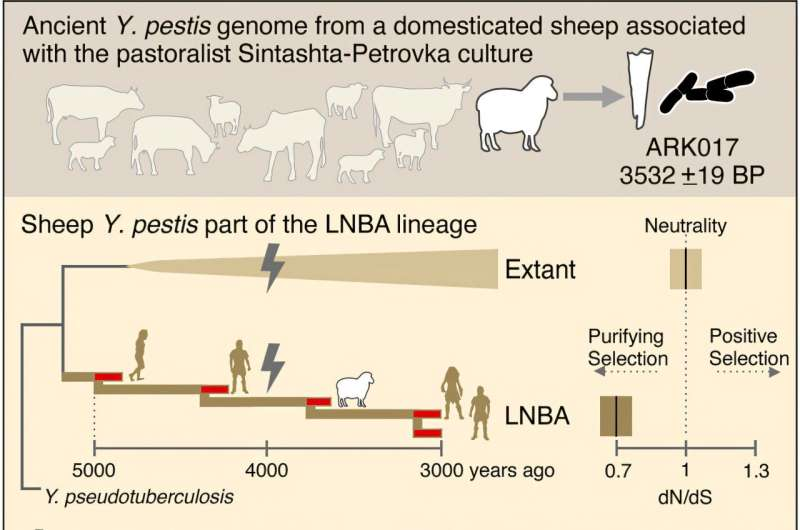

A recent international study has uncovered the first-ever evidence of Bronze Age plague infection in a non-human animal, shedding light on how an early form of plague circulated for nearly 2,000 years before disappearing. The findings come from the recovery of Yersinia pestis DNA — the bacterium responsible for plague — from a 4,000-year-old sheep found at the ancient site of Arkaim, located in the Southern Ural Mountains of present-day Russia near the Kazakhstan border.

This discovery doesn’t just add a new data point. It fundamentally reshapes how scientists understand the ecology, transmission, and evolution of prehistoric plague.

Understanding the Bronze Age Plague Problem

Most people associate plague with the Black Death, which devastated Europe during the Middle Ages and killed an estimated one-third of the population. That medieval pandemic was spread primarily by fleas, which carried Yersinia pestis from infected rats to humans.

However, genetic studies over the past decade have shown that an earlier strain of plague emerged around 5,000 years ago, during the Bronze Age. This ancient lineage infected human populations across Eurasia for thousands of years — from Europe to Central Asia — and then vanished.

Here’s the problem scientists faced: this Bronze Age strain lacked the genetic mutations needed for flea-based transmission. In other words, it couldn’t spread the way medieval plague did. Yet archaeological evidence clearly shows the same plague strain appearing in human remains separated by thousands of kilometers.

Something wasn’t adding up.

The Sheep Discovery at Arkaim

The breakthrough came from Arkaim, a fortified Bronze Age settlement associated with the Sintashta culture, a society known for early horse riding, advanced bronze weaponry, and extensive mobility across the Eurasian steppe.

While analyzing ancient livestock remains excavated from Arkaim in the 1980s and 1990s, researchers detected something unexpected. One sheep bone contained ancient DNA fragments belonging to Yersinia pestis.

This was a major surprise. Until now, all confirmed Bronze Age plague genomes had come exclusively from human remains. This sheep represents the first non-human host ever identified for this prehistoric plague lineage.

Recovering this genome was no small feat. Ancient livestock DNA is notoriously difficult to work with due to:

- Heavy environmental contamination from soil microbes

- Human contamination from excavation and handling

- DNA degradation caused by cooking, exposure, and disposal practices

- Extremely short DNA fragments, often only about 50 base pairs long

Despite these challenges, the team successfully reconstructed enough of the bacterial genome to confirm that the sheep was infected with the same Bronze Age plague lineage found in humans.

Why This Changes Everything

The sheep discovery provides a crucial missing link in understanding how the Bronze Age plague spread.

Rather than moving solely through human-to-human contact, researchers now believe the plague operated within a complex system involving humans, livestock, and a natural reservoir.

The emerging model looks like this:

- A natural reservoir — possibly wild rodents of the Eurasian steppe or even migratory animals — carried Y. pestis without becoming severely ill

- Livestock such as sheep became infected through environmental exposure while grazing or interacting with wildlife

- Humans then contracted the disease through close contact with animals, including herding, slaughtering, and daily handling

This kind of multi-host transmission system helps explain how the plague could persist for millennia and appear repeatedly in distant human populations without relying on fleas.

The Role of Bronze Age Lifestyles

The timing of this plague is no coincidence. The Bronze Age marked a period of dramatic social and economic change, especially in the Eurasian steppe.

Key developments included:

- Larger domesticated herds of sheep, cattle, and goats

- Increased mobility, including early horse riding

- Seasonal movement into new grazing territories

- More frequent contact with wild ecosystems

These shifts created ideal conditions for diseases to jump between species. As humans and animals moved together across wide landscapes, pathogens could travel with them — even if transmission was inefficient by modern standards.

In this context, sheep and other livestock likely acted as bridge hosts, carrying the bacterium across regions and reintroducing it to human populations over time.

Why the Bronze Age Plague Eventually Disappeared

Unlike later plague pandemics, the Bronze Age strain of Yersinia pestis never evolved the ability to spread efficiently via fleas. Without that adaptation, transmission likely remained slow, localized, and dependent on repeated spillover events from animal reservoirs.

Over time, changes in human behavior, climate, ecosystems, or pathogen evolution may have disrupted this fragile transmission network. Eventually, the lineage faded out, leaving behind only genetic traces in ancient bones.

Ironically, it was the later evolution of flea-based transmission that allowed plague to become far deadlier and more explosive during historical pandemics.

What This Discovery Means Today

While this research focuses on events thousands of years in the past, it carries a clear modern lesson. Many of today’s emerging diseases are zoonotic, meaning they originate in animals before infecting humans.

The Bronze Age plague shows that:

- Pathogens don’t need rapid transmission to persist long-term

- Human expansion into new environments increases disease risk

- Domesticated animals can act as critical intermediaries

- Ecosystem balance plays a major role in disease emergence

As modern societies continue to reshape landscapes for agriculture, urbanization, and resource extraction, the same dynamics that fueled ancient outbreaks remain relevant.

Why Sheep Matter More Than We Thought

Sheep have accompanied humans for over 10,000 years, shaping economies, diets, and cultures across continents. This discovery adds another layer to their historical importance — their role in ancient disease networks.

By analyzing ancient livestock DNA, researchers can now explore:

- How diseases moved alongside early farming and herding

- When pathogens adapted to new hosts

- How human-animal relationships influenced epidemic history

This single sheep from Arkaim has opened an entirely new window into the prehistoric past.

Looking Ahead

Researchers plan to continue excavating and analyzing human and animal remains from the Southern Urals, searching for more evidence of ancient plague infections. Each new genome could help identify the elusive natural reservoir and clarify how prehistoric diseases shaped early societies.

What’s clear now is that the Bronze Age plague wasn’t just a human disease. It was part of a shared biological landscape, connecting people, animals, and environments in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Research Paper:

https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(25)00851-7