Giant Clams in American Sāmoa Are Thriving Thanks to Indigenous Village-Based Management

A new scientific study has revealed some genuinely encouraging news for coral reef conservation: giant clams in American Sāmoa are not only surviving, but thriving, largely due to long-standing Indigenous, community-led management practices. Contrary to widespread assumptions that these iconic reef species are in steep decline, researchers found that clam populations across the territory have remained stable and abundant for decades, especially in areas managed by local villages.

The research was led by scientists from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB), specifically the ToBo Lab, and was published in the peer-reviewed journal PeerJ in late 2025. By combining historical survey records with extensive new fieldwork, the team produced the most complete multi-decadal dataset on giant clams ever assembled for American Sāmoa.

A Long-Term Look at Giant Clam Populations

The study analyzed data from surveys that began in 1994 and extended through 2024, covering a full 30-year period. Between 2022 and 2024 alone, researchers added 264 new survey transects, dramatically expanding the scope and precision of earlier efforts.

In total, the dataset spans six islands in American Sāmoa and includes multiple types of management zones, ranging from village-managed reef closures to federally designated no-take marine reserves. This allowed researchers to directly compare how different conservation approaches affect giant clam populations over time.

The results were striking. Across the territory, giant clam abundance has remained remarkably stable, even near populated islands where fishing pressure and coastal development might be expected to cause declines. In some locations, clam densities were not just stable but consistently high.

Village Management Outperforms Federal No-Take Reserves

One of the most important findings of the study was that village-managed marine areas consistently supported higher densities and larger-sized clams than federally protected no-take zones. This runs counter to the assumption that stricter, centralized protections automatically lead to better conservation outcomes.

In American Sāmoa, many villages maintain traditional systems of marine stewardship, including periodic reef closures, harvest restrictions, and community enforcement. These practices are deeply rooted in cultural values and social accountability, which appear to translate into real ecological benefits.

In contrast, several federally managed no-take areas showed some of the lowest clam densities recorded in the study. The researchers suggest this may be due to challenges in enforcement, reduced community engagement, or management approaches that do not align well with local ecological and cultural realities.

Challenging Assumptions About Decline

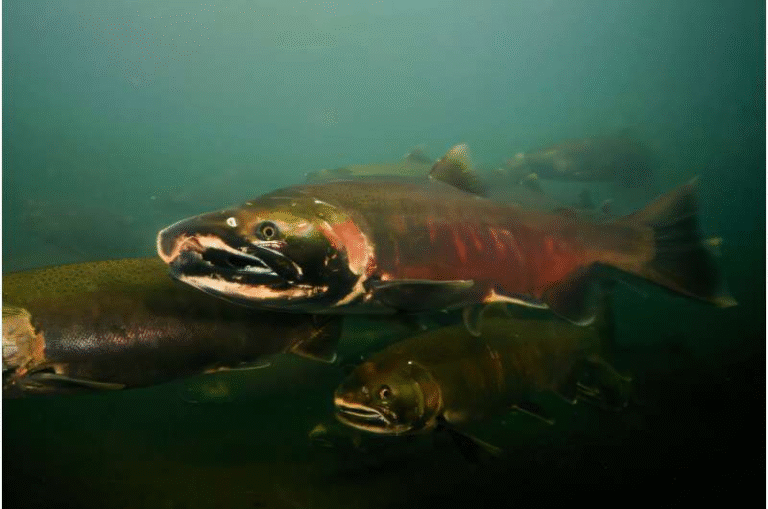

Giant clams are often portrayed as highly vulnerable and rapidly disappearing across the Indo-Pacific. While this is true in many regions, the American Sāmoa data tell a more nuanced story.

The dominant species observed was Tridacna maxima, which accounted for nearly 97 percent of all clams recorded. Smaller numbers of other species, including Tridacna squamosa and Tridacna noae, were also documented.

Some of the highest clam densities were found in remote locations such as Ta‘ū Island and Rose Atoll (Muliāva), with estimates reaching hundreds to over a thousand clams per hectare. Even around the main island of Tutuila, where human activity is greatest, clam populations showed long-term stability rather than collapse.

These findings suggest that local context matters enormously when assessing species risk and conservation needs.

Implications for the Endangered Species Act

The study arrives at a critical moment, as U.S. federal agencies are currently considering whether to list giant clams under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

The researchers caution that a blanket ESA listing could have unintended consequences in places like American Sāmoa, where traditional management systems have demonstrably maintained healthy clam populations. Under ESA regulations, many customary harvesting and stewardship practices could become illegal, even if they have proven effective for generations.

The data show that federal protection alone does not guarantee better outcomes, and in some cases may perform worse than Indigenous-led management. The study argues that conservation policy should recognize and support locally successful governance systems, rather than overriding them with one-size-fits-all regulations.

Collaboration at the Heart of the Research

Another defining feature of the study was its deep collaboration with local partners. The research team worked closely with:

- The American Sāmoa Department of Marine and Wildlife Resources

- The National Park of American Sāmoa

- The National Marine Sanctuary of American Sāmoa

- Village councils and local resource managers

This Pacific-to-Pacific partnership strengthened both the scientific outcomes and the relevance of the research. It also reinforced the idea that effective conservation is as much social as it is ecological.

Why Giant Clams Matter to Reef Ecosystems

Beyond their cultural and economic importance, giant clams play key ecological roles on coral reefs. They host symbiotic algae within their tissues, which allows them to convert sunlight into energy, much like corals do. This relationship contributes to reef productivity and nutrient cycling.

Giant clams also act as natural water filters, improving water clarity and creating microhabitats for other reef organisms. Their shells provide structure and shelter, enhancing overall reef complexity.

Because of these roles, healthy clam populations are often a sign of well-functioning reef ecosystems.

Lessons Beyond American Sāmoa

While the study focuses on American Sāmoa, its implications extend far beyond the territory. Many coastal regions around the world are re-examining the role of Indigenous knowledge and community-based management in conservation.

The findings provide strong evidence that locally governed marine stewardship can match or exceed centralized protection, especially when it is culturally embedded and actively enforced. These lessons are already informing conversations in Hawaiʻi and other Pacific Islands, where efforts are underway to revive traditional resource management systems and restore coastal fisheries.

A Data-Rich Foundation for Future Conservation

With its 30-year scope and territory-wide coverage, this research establishes a robust baseline for future monitoring of giant clams in American Sāmoa. It also highlights the importance of long-term data in challenging assumptions and shaping smarter policy decisions.

Rather than framing conservation as a choice between tradition and science, the study shows how science and Indigenous stewardship can reinforce each other, producing outcomes that benefit both ecosystems and communities.

Research Paper Reference:

Paolo Marra-Biggs et al., Status and trends of giant clam populations demonstrate the effectiveness of village-based protection in American Sāmoa, PeerJ (2025).

https://peerj.com/articles/20290/