Scientists Discover How Plant Roots and Vines Twist and Turn to Overcome Obstacles

Twisted growth is one of the most fascinating and widespread strategies plants use to survive. From morning glories spiraling up fence posts to grapevines corkscrewing through trellises, twisting allows plants to anchor themselves, climb toward sunlight, and navigate difficult environments underground. Now, scientists have uncovered a long-missing piece of the puzzle: how plants actually control this twisting growth at the cellular and mechanical level.

A new study published in Nature Communications reveals that the key driver behind twisted growth in plant organs—especially roots—is not deep inside the plant, as many researchers once assumed. Instead, the answer lies in the epidermis, the thin outer layer of cells that surrounds the organ. This discovery helps explain why twisted growth is so common across the plant kingdom and opens new possibilities for agriculture and plant engineering.

Why Twisted Growth Matters in Plants

Plants cannot move from place to place, but they are far from passive. Roots constantly twist and skew as they grow through soil, dodging rocks, compacted layers, and other underground obstacles. Above ground, twisting helps vines climb, stems resist wind, and plants anchor themselves against erosion.

Scientists have known for years that twisting often appears when certain genes related to microtubules—tiny structural components inside plant cells—are disrupted. These disruptions usually came from null mutations, where a gene is completely knocked out. While these mutations caused twisting, they also raised a major question.

If twisted growth were simply the result of broken genes, why would it be such a widespread and evolutionarily useful trait? Completely losing important genes should create many harmful side effects, yet twisting clearly benefits plants in many environments.

A Clue Hidden in the Epidermis

The new research was led by Ram Dixit, a biology professor at Washington University in St. Louis, along with his former Ph.D. student Natasha Nolan and mechanical engineer Guy Genin. Their work emerged from the National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center for Engineering Mechanobiology (CEMB), a collaborative effort that brings together biologists, engineers, and physicists.

Instead of focusing on complete gene loss, the researchers explored whether localized changes in gene expression could explain twisting. Their experiments used a model plant system where roots naturally skew either to the right or left, making twisting easy to observe and measure.

What they found was striking: plants do not need full gene knockouts to twist. All it takes is a change in how certain genes behave specifically in the epidermis. This simple adjustment can trigger twisted growth without disrupting the rest of the plant.

Testing Which Cell Layer Controls the Twist

Plant roots are made of multiple concentric layers of cells, much like rings in a tree trunk. For a long time, scientists believed twisting originated in the inner cortical layer, where mutant cells often appear short and wide instead of long and narrow. The idea was that the outer layers were forced to bend and twist to accommodate these misshapen inner cells.

To test this, the researchers used a clever genetic approach. Instead of restoring the normal gene throughout the entire root, they restored it only in specific cell layers.

The results were clear and surprising:

- When the normal gene was restored in inner layers, the roots still twisted exactly like mutant plants.

- When the normal gene was restored only in the epidermis, the roots grew straight, even though the inner layers still carried the mutation.

This showed that the epidermis dominates the twisting behavior. If the epidermis is straight, the entire root straightens. If the epidermis twists, the whole root follows.

How the Epidermis Controls the Whole Organ

Discovering that the epidermis controls twisting was only half the story. The next question was why this outer layer has so much power.

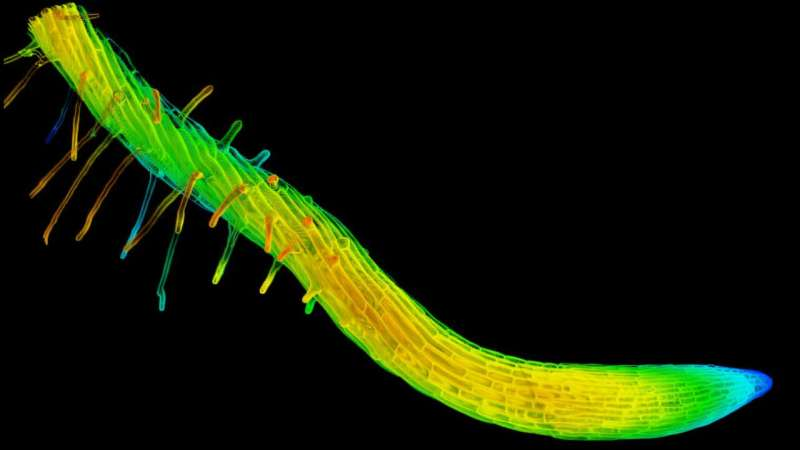

This is where mechanical modeling came in. Researchers measured the orientation of cellulose microfibrils—the stiff fibers that reinforce plant cell walls—in both twisted and straight roots. Twisted roots showed altered cellulose patterns, especially in the epidermis.

Using these measurements, mechanical models revealed a fundamental principle: geometry matters enormously. In structures made of concentric layers, the outermost layer has far more influence over overall shape and mechanical behavior than inner layers. This is the same physics that explains why hollow tubes can be nearly as strong as solid rods when twisted.

The model showed that if only the epidermis has skewed cell alignment, it can drive about one-third of the total twisting seen when every layer is skewed. More importantly, fixing just the epidermis is enough to straighten the entire root.

The Epidermis as a Mechanical Coordinator

One of the most intriguing findings was how the epidermis affects inner cell layers. When the epidermis was corrected, inner cortical cells—despite still carrying mutations—changed shape. They became longer and slimmer, resembling normal cells rather than mutant ones.

This suggests that the epidermis is not just a passive protective layer. It acts as a mechanical coordinator, transmitting forces inward and influencing how deeper cells grow and expand. In other words, the epidermis entrains the rest of the organ, guiding its overall growth pattern.

Why This Discovery Matters for Agriculture

Understanding root mechanics is becoming increasingly important as climate change intensifies droughts and pushes farming onto rocky, compacted, and nutrient-poor soils. Roots are often called the hidden half of agriculture, because a plant’s ability to find water and nutrients depends entirely on how its roots explore the soil.

This research suggests that it may be possible to tune root behavior by targeting the epidermis. Crops could potentially be designed to increase twisting in harsh soils, allowing roots to corkscrew around obstacles, or reduce twisting where straight penetration is more efficient.

Beyond roots, twisted growth also affects vines, stems, and anchoring systems, making this discovery relevant to ecosystem stability, erosion control, and plant resilience.

Extra Insight: Twisted Growth Across the Plant World

Twisted or chiral growth is not limited to roots. Many plant structures show natural helices, including tendrils, stems, and climbing shoots. This growth often emerges from interactions between microtubules, cellulose deposition, and mechanical stress.

What makes this new study especially important is that it connects molecular biology, cellular architecture, and physical mechanics into one coherent framework. Instead of viewing twisting as a genetic accident, it frames it as an engineered growth strategy governed by simple physical rules.

A Clearer Picture of How Plants Shape Themselves

This research demonstrates the power of interdisciplinary science. Biology alone identified the genes involved, while engineering explained why the epidermis rules from a mechanical standpoint. Together, they reveal how plants translate tiny cellular asymmetries into large-scale, functional shapes.

With this knowledge, scientists now have a clearer roadmap for understanding—and potentially redesigning—plant architecture in a rapidly changing world.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66029-8