RIKEN Scientists Reveal How Molecular Chirality Shapes the Directional Behavior of Living Cells

Researchers at Japan’s RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research have uncovered an important missing link in biology: how the handedness of molecules inside our cells can lead to directional, asymmetric behavior at the cellular level. This discovery helps explain one of the most fundamental mysteries in developmental biology—why living organisms, including humans, are not perfectly symmetrical from left to right.

Understanding Chirality From Molecules to Cells

Chirality is a concept borrowed from chemistry and physics, referring to objects that exist in left- and right-handed forms that cannot be superimposed on each other, like human hands. Life on Earth is deeply chiral. DNA forms a right-handed helix, amino acids are mostly left-handed, and many proteins and cellular components follow strict chiral rules.

What has remained unclear for decades is how this molecular chirality translates into larger biological patterns. For example, most human organs are asymmetrically positioned: the heart typically sits on the left, the liver on the right. Scientists have long suspected that these large-scale asymmetries originate from much smaller asymmetries inside cells, but the exact mechanism has been elusive.

Why Cellular Chirality Matters

Cells themselves can be chiral, meaning they show consistent left- or right-biased behavior. This cellular chirality is believed to influence how tissues grow and how organs ultimately form their left–right identity. If cellular chirality were reversed, it is theoretically possible that organ placement could also flip, resulting in mirror-image anatomy.

The RIKEN team, led by Tatsuo Shibata, set out to understand how individual cells acquire this directional bias and whether it can be traced directly to the chirality of molecules within the cell.

Inspiration From Fruit Fly Development

The researchers’ interest in this question began with studies on fruit flies. In developing flies, certain tissues—specifically genital discs—always rotate in a clockwise direction. This rotation is highly consistent, suggesting a deeply rooted biological mechanism rather than random motion.

By examining this phenomenon, the team became interested in tracing chirality backward: from tissue-level rotation, to individual cell behavior, and ultimately to molecular interactions. The key question was whether molecular chirality alone could drive cellular asymmetry without requiring an already asymmetric cell structure.

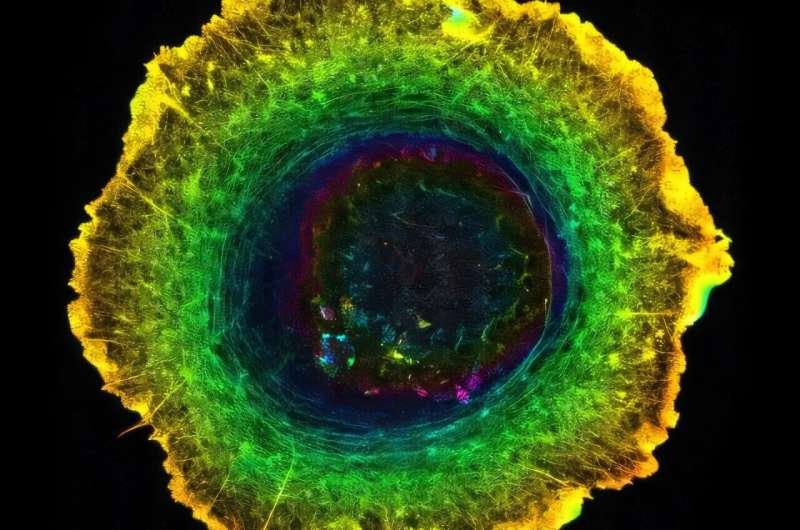

Observing Single Cells in Action

To investigate this, the researchers studied isolated epithelial cells placed on a flat substrate. When viewed from above, something remarkable happened: the cell nucleus and surrounding cytoplasm rotated in a consistent clockwise direction. This occurred even though the overall shape of the cell appeared symmetrical.

This observation immediately suggested that the source of the rotation was internal rather than structural. The team focused their attention on the cytoskeleton—the internal scaffold that gives cells their shape and mechanical strength.

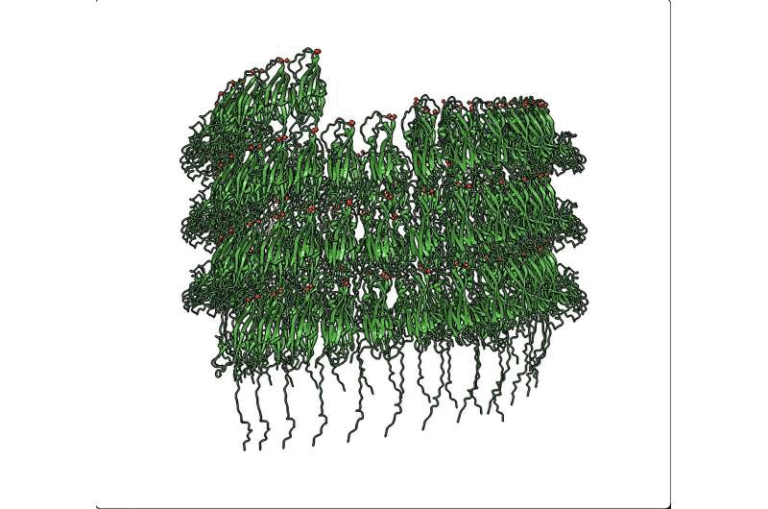

The Role of the Actomyosin Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is made up of protein filaments, including actin and myosin. These molecules are not only essential for maintaining cell shape but also for movement, division, and force generation. Importantly, both actin and myosin are chiral at the molecular level.

Using advanced microscopy, the researchers found that actin and myosin filaments formed a dynamic concentric pattern within the cell. Rather than aligning randomly, these filaments arranged themselves in circular structures that generated rotational forces.

This concentric actomyosin pattern turned out to be the driver of the clockwise rotation observed in the nucleus and cytoplasm. In other words, molecular-scale chirality was being converted into mechanical torque, resulting in visible cellular motion.

No Need for a Chiral Cell Shape

One of the most surprising findings of the study is that cellular rotation occurred even in the absence of an obvious chiral structure at the cell level. The cells did not need to be asymmetrically shaped or oriented in a particular direction. The rotation emerged purely from the internal dynamics of the cytoskeleton.

This challenges previous assumptions that visible asymmetry at the cellular level was required for directional behavior. Instead, the study shows that local molecular interactions can produce global cellular effects.

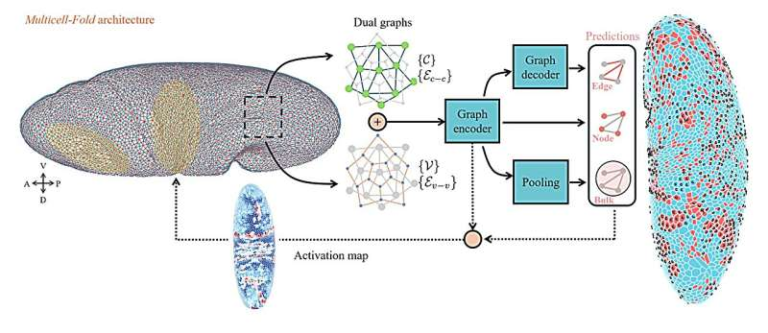

Confirming the Mechanism With Theoretical Models

To further validate their observations, the researchers built a three-dimensional theoretical model of a cell. This model incorporated the known physical properties of actin and myosin, including their molecular chirality.

The simulations demonstrated that tiny torques generated by individual cytoskeletal components could add up, producing sustained rotational motion at the cellular level. Even when the model lacked any predefined chiral cell architecture, rotation still emerged naturally.

This theoretical work confirmed that molecular chirality alone is sufficient to drive cellular chirality, bridging a crucial gap in our understanding of biological asymmetry.

Implications for Organ Development and Body Asymmetry

These findings have major implications for developmental biology. Left–right symmetry breaking is one of the earliest and most critical steps in embryonic development. Errors in this process can lead to serious congenital conditions, including reversed organ placement or heart defects.

By showing how molecular chirality can generate cellular chirality without external cues, the study provides a plausible mechanism for how asymmetry propagates upward—from molecules, to cells, to tissues, and finally to organs.

The researchers emphasize that this work represents a key missing link in the chain connecting molecular structure to whole-body organization.

Broader Context: Chirality in Living Systems

Chirality is not limited to cells and organs. It appears across many levels of biology, from spiral growth patterns in plants to the coiling of snail shells. Even bacteria can exhibit chiral movement when swimming or forming colonies.

Understanding how chirality emerges and propagates is therefore relevant far beyond human anatomy. It could inform research in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and synthetic biology, where controlling cell orientation and behavior is crucial.

Additionally, these insights may help scientists design better biomimetic materials that harness chiral forces at the molecular level to produce controlled motion or structure.

What This Study Adds to Science

This research stands out because it clearly demonstrates that directional cellular behavior does not require pre-existing asymmetry. Instead, chirality can emerge naturally from the fundamental properties of molecular components inside the cell.

By combining live-cell imaging, experimental biology, and theoretical modeling, the RIKEN team has provided one of the clearest explanations to date of how microscopic chirality scales up to macroscopic biological patterns.

Looking Ahead

While this study focuses on epithelial cells, future research may explore whether similar mechanisms operate in other cell types and organisms. Scientists are also interested in understanding how cellular chirality interacts with genetic and biochemical signaling during development.

Ultimately, this work brings us closer to answering a deceptively simple question with profound implications: why living bodies are shaped the way they are.

Research paper:

Takaki Yamamoto et al., Epithelial cell chirality emerges through the dynamic concentric pattern of actomyosin cytoskeleton, eLife (2025)

https://elifesciences.org/articles/102296