Scientists Discover How Different GPCR Drugs Trigger Stronger or Weaker Cellular Signals

G-protein coupled receptors, better known as GPCRs, are some of the most important proteins in the human body. They sit on the surface of cells and act like highly sensitive antennas, picking up signals from outside the cell and passing those messages inward. These signals influence everything from pain perception and mood to growth, metabolism, and neurotransmission. Because of this central role, GPCRs are also one of the biggest targets in modern medicine, accounting for roughly one-third of all FDA-approved drugs.

Despite decades of research, one major puzzle has remained unsolved: why do different drugs that bind to the same GPCR produce different strengths of the same biological effect? A new study published in Nature by researchers at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital finally provides a clear structural and kinetic explanation—and it could have major implications for drug design, especially for pain medications.

GPCR Activation Is Not a Simple On-Off Switch

For a long time, GPCR activation was thought of as a fairly simple process. A ligand—essentially a signaling molecule or drug—binds to the receptor, the receptor changes shape, and a G protein inside the cell becomes activated. That activated G protein then triggers downstream signaling pathways.

The new research shows that reality is far more complex.

Instead of flipping instantly from “inactive” to “active,” GPCRs move through a series of intermediate shapes, known as conformational states, before fully activating the G protein. These shape changes are not smooth or effortless. Along the way, the receptor must cross energy barriers, and sometimes it gets temporarily stuck in what scientists call kinetic traps.

What Are Kinetic Traps and Why They Matter

A kinetic trap is an intermediate state where the receptor pauses because it requires extra energy to move forward. The researchers use a helpful analogy: imagine rolling a ball downhill. If the hill has small dents or divots, a lighter ball might get stuck briefly, while a heavier ball rolls through without slowing down.

In this case, the ball is the GPCR, and the push comes from the ligand bound to it.

The study found that different ligands push the receptor through the same activation steps, but at different speeds. Importantly, all ligands eventually lead to the same final active state. What differs is how fast they move the receptor through those intermediate steps.

Partial, Full, and Super Agonists Compared

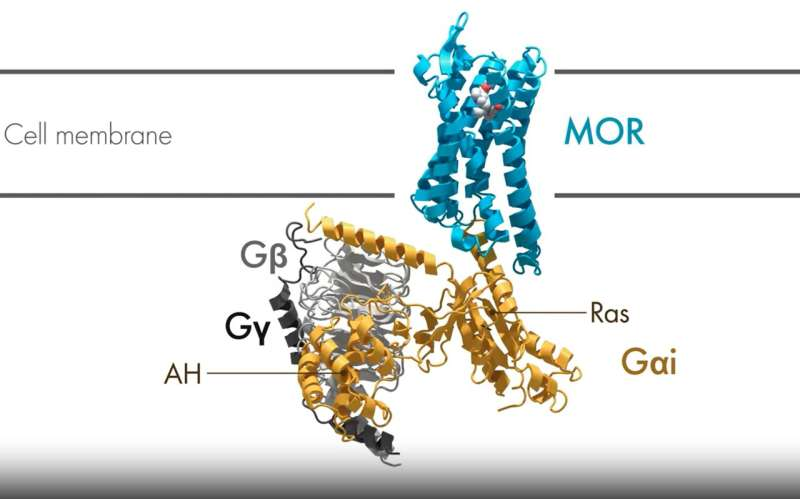

The researchers focused on the μ-opioid receptor (MOR), one of the most well-studied GPCRs and the primary target of pain-relief drugs like morphine and codeine. They compared three categories of ligands:

- Partial agonists, which produce weaker signaling

- Full agonists, which generate strong signaling

- Super agonists, which trigger even stronger responses than typical full agonists

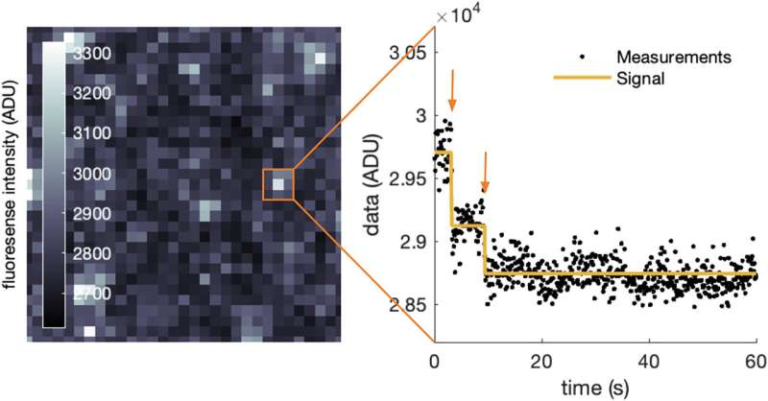

Using advanced cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM), the team captured multiple structural snapshots of the receptor and its associated G protein as activation unfolded over time. These snapshots effectively created “molecular movies” of the activation process.

What they observed was striking. Partial agonists caused the receptor to linger much longer in specific intermediate states, especially near the final stages before G-protein release. Full and super agonists, on the other hand, pushed the receptor through these steps much more quickly.

Speed, Not Structure, Explains Efficacy

One of the most important findings of the study is that the final activated structure of the receptor looks the same regardless of which agonist is used. This means the difference in drug efficacy does not come from ending up in a different shape.

Instead, efficacy is determined by how fast the receptor moves through the activation pathway.

Partial agonists make the receptor more rigid, slowing its ability to overcome energy barriers. This rigidity increases the likelihood of becoming trapped in intermediate states. Full agonists allow more flexibility, while super agonists make the receptor especially dynamic, enabling it to breeze through kinetic traps.

Single-Molecule Imaging Confirms the Mechanism

To strengthen their conclusions, the researchers combined cryoEM data with single-molecule imaging techniques. These experiments allowed them to track individual receptor-G protein interactions in real time.

The single-molecule data confirmed that partial agonists do not fail to activate the receptor—they simply do so more slowly. Given enough time, even partial agonists can push the receptor all the way to full activation. This explains why partial agonists still work, but produce weaker overall effects.

Why This Matters for Drug Development

Understanding GPCR activation at this level of detail could reshape how drugs are designed. Traditionally, drug discovery has focused on binding strength and receptor occupancy. This study shows that activation kinetics—how quickly a drug pushes a receptor through its conformational changes—are just as important.

For opioid drugs in particular, this insight is especially valuable. The ongoing opioid epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for pain relievers that are effective but safer. If scientists can design drugs that carefully control activation speed, it may be possible to fine-tune pain relief while reducing harmful side effects.

A Broader Impact Beyond Opioid Receptors

While this study focuses on the μ-opioid receptor, the findings likely apply to many GPCRs across biology. Since GPCRs regulate such a wide range of physiological processes, understanding their dynamic behavior opens new doors in treating neurological disorders, metabolic diseases, cardiovascular conditions, and more.

This research also challenges the traditional view of receptors as static entities. Instead, GPCRs should be thought of as constantly shifting molecular machines, where timing and movement matter just as much as structure.

Extra Context: Why GPCRs Are So Important

GPCRs form the largest family of membrane receptors in humans, with over 800 identified members. They respond to hormones, neurotransmitters, sensory stimuli like light and smell, and even mechanical forces. Because they sit at the interface between the cell and its environment, they are ideal drug targets.

However, this same complexity makes them difficult to study. Capturing transient intermediate states requires cutting-edge technology like cryoEM and sophisticated data analysis. This study represents a major technical achievement in addition to its biological insights.

The Big Takeaway

The key message from this research is simple but powerful: different GPCR ligands do not change what the receptor becomes, they change how fast it gets there. Partial agonists, full agonists, and super agonists all follow the same activation pathway, but their ability to overcome kinetic traps determines the strength of the signal.

By revealing this hidden layer of GPCR behavior, scientists now have a clearer roadmap for designing drugs that are not just potent, but precisely controlled.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-10056-4