Ancient Sea Anemone Research Reveals How Animal Cell Types Evolved Hundreds of Millions of Years Ago

Understanding how a single genome can produce the astonishing diversity of cell types found in animals has long been one of biology’s biggest unanswered questions. Every neuron, muscle cell, and skin cell carries the same DNA, yet they behave, look, and function very differently. A new study centered on an unassuming marine animal, the starlet sea anemone, is now offering some of the clearest insights yet into how this diversity first evolved.

Researchers have created the first comprehensive map of gene regulatory elements across cell types in Nematostella vectensis, a small sea anemone that belongs to one of the most ancient animal lineages on Earth. By shifting the focus away from which genes are active and instead examining how genes are controlled, the study opens a new window into animal cell type evolution and suggests that many of the rules governing our own cells are far older than previously believed.

Why Gene Regulation Matters More Than Genes Alone

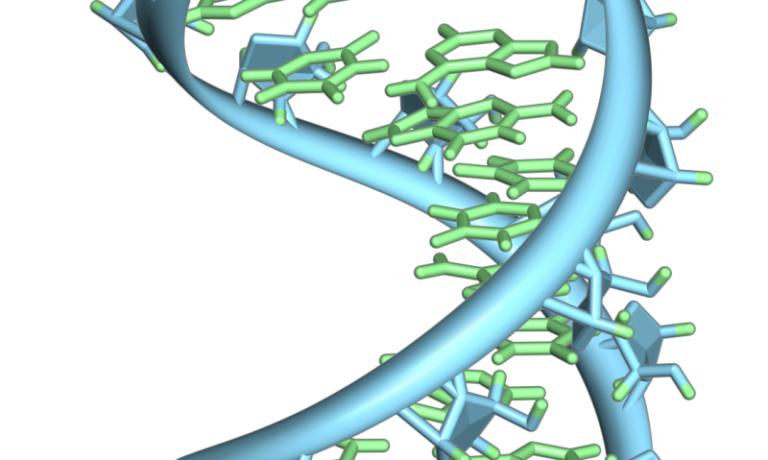

At the heart of this research is a simple but powerful idea: genes do not act alone. What truly defines a cell’s identity is gene regulation, the system of molecular switches that determines which genes are turned on or off in a particular cell.

These switches are known as regulatory elements, short regions of DNA that control gene activity. They act like permissions in a complex operating system, deciding when and where a gene can be used. While scientists have studied regulatory elements extensively in classic laboratory organisms such as mice and fruit flies, far less was known about how these systems operate in early-diverging animals.

That gap is what this new research set out to fill.

Mapping the Regulatory Landscape of a Sea Anemone

The research team analyzed nearly 60,000 individual cells from Nematostella vectensis. About 52,000 cells came from adult animals, while around 7,000 cells were taken from gastrula-stage embryos, a critical early developmental phase when the basic body plan is first established.

Using advanced single-cell genomic techniques, the scientists identified 112,728 regulatory elements across the sea anemone’s genome. This number is striking when compared to the animal’s relatively modest genome size of about 269 million DNA letters. In fact, the total number of regulatory elements approaches that found in the fruit fly Drosophila, an organism that evolved hundreds of millions of years later.

This finding alone suggests that the regulatory toolkit for complex animal life emerged very early, long before animals developed elaborate body structures.

A New Way to Classify Cell Types

Traditionally, scientists classify cell types based on gene expression, meaning which genes are active in a cell. This approach groups cells by what they do. However, the new regulatory atlas reveals something deeper.

When cells are grouped based on shared regulatory elements, they cluster according to their developmental origin, specifically the embryonic germ layer they came from. Germ layers are the foundational tissues formed early in development that later give rise to all organs and structures.

This distinction led to one of the study’s most surprising discoveries. The researchers examined two types of muscle cells that look nearly identical, contract in similar ways, and use many of the same genes. Despite these similarities, the cells originated from different germ layers, and their genes were controlled by entirely different regulatory elements.

In other words, cells can arrive at similar functions through very different regulatory paths. This insight has major implications for understanding both development and evolution.

What This Tells Us About Evolution

Sea anemones belong to the group Cnidaria, which also includes jellyfish and corals. These animals appeared on Earth roughly 500 million years ago and represent some of the earliest forms of multicellular animal life.

Cnidarians are especially important because they were among the first animals to evolve neurons and muscle cells. They also possess a unique cell type called cnidocytes, which contain tiny, harpoon-like structures used for hunting and defense. These cells are responsible for the familiar sting of jellyfish and sea anemones.

The new regulatory atlas provides a framework for understanding how such specialized cells may have evolved. Rather than requiring entirely new genes, evolution can create new cell types by rewiring existing regulatory networks. Small changes in regulatory elements can produce large changes in cell behavior, making gene regulation a powerful driver of evolutionary innovation.

Deep Learning Meets Ancient Genomes

Another important aspect of the study is its use of deep learning models to analyze DNA sequences. By combining single-cell data with machine learning, the researchers were able to decode patterns in regulatory DNA that predict how specific cell types are maintained.

This approach moves beyond cataloging regulatory elements and begins to uncover the rules encoded in the genome itself. These rules explain how networks of regulatory elements work together to define stable cell identities across development and evolution.

Why the Scale of the Discovery Is So Important

The sheer scale of the regulatory map is one of the study’s most remarkable features. Finding over 112,000 regulatory elements in such an early-diverging animal challenges the idea that regulatory complexity evolved gradually alongside physical complexity.

Instead, the results suggest that the genetic instructions needed for complex cell behavior existed long before complex animal bodies did. The same basic regulatory principles that allow human neurons to fire or muscles to contract today were already present in simple animals drifting through ancient seas.

Additional Context: What Are Regulatory Elements?

To fully appreciate the study, it helps to understand what regulatory elements do. These DNA regions include enhancers, silencers, and promoters, each playing a role in controlling gene activity. Unlike genes, regulatory elements do not code for proteins. Instead, they influence when, where, and how strongly genes are expressed.

Because regulatory elements can evolve independently of genes, they provide a flexible way for evolution to generate diversity without disrupting essential biological functions.

Why Sea Anemones Are Ideal for This Kind of Research

Nematostella vectensis has become a popular model organism because it combines evolutionary significance with modern genetic accessibility. Its relatively simple body plan and slow evolutionary rate make it easier to identify ancient genetic features that are shared with more complex animals.

By studying organisms like sea anemones, scientists can reconstruct the early steps that led to the diversity of life seen today.

What Comes Next

As more species are analyzed using similar approaches, researchers will be able to compare regulatory atlases across the animal tree of life. This will help answer fundamental questions about which regulatory circuits are ancient, which are newly evolved, and how changes in gene regulation give rise to new cell types.

For the first time, scientists now have a systematic and scalable way to study cellular evolution at the level of DNA regulation, rather than just gene expression.

Research Paper:

Decoding cnidarian cell type gene regulation, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-025-02906-1