Scientists Discover How Light-Sensing Genes Drive the Formation of New Coral Species

Marine scientists have long been fascinated by coral reefs. These ecosystems host an astonishing amount of biodiversity, yet the exact biological mechanisms that generate so many coral species have remained surprisingly unclear. A new study published in Nature Communications now sheds light—quite literally—on how new coral species form. Researchers have identified molecular mechanisms tied to light perception that help explain how corals split into distinct species, even when they live just meters apart.

The research was led by Matías Gómez-Corrales, a recent Ph.D. graduate in biological sciences from the University of Rhode Island (URI), along with his advisor Carlos Prada, an associate professor of biological sciences. Their work builds on decades of coral research and proposes a compelling new explanation for speciation in the ocean, a topic that has challenged evolutionary biologists for years.

Why Coral Speciation Has Been Such a Puzzle

Unlike land animals, many marine species do not face obvious physical barriers like mountains or rivers that separate populations. Corals often release eggs and sperm into open water, which should, in theory, promote mixing rather than separation. For a long time, scientists believed that coral speciation mainly resulted from rapid evolution of sperm–egg compatibility proteins, allowing closely related species to avoid cross-fertilization.

While that explanation still holds some truth, it does not fully account for the remarkable diversity seen on coral reefs. The new study introduces a complementary idea: adaptation to different light environments across depth gradients can directly lead to reproductive isolation.

Corals, Light, and an Unexpected Sensory Ability

One of the most important relationships in coral biology is the mutualism between reef-building corals and dinoflagellate algae. These microscopic algae live inside coral tissues and provide more than 90% of the coral’s energy through photosynthesis. Because of this dependence, corals are extremely sensitive to light conditions.

Light changes dramatically with depth. Shallow waters receive bright, broad-spectrum sunlight, while deeper waters are dominated by dimmer, blue-shifted wavelengths. Corals living at different depths must adapt to these conditions to survive.

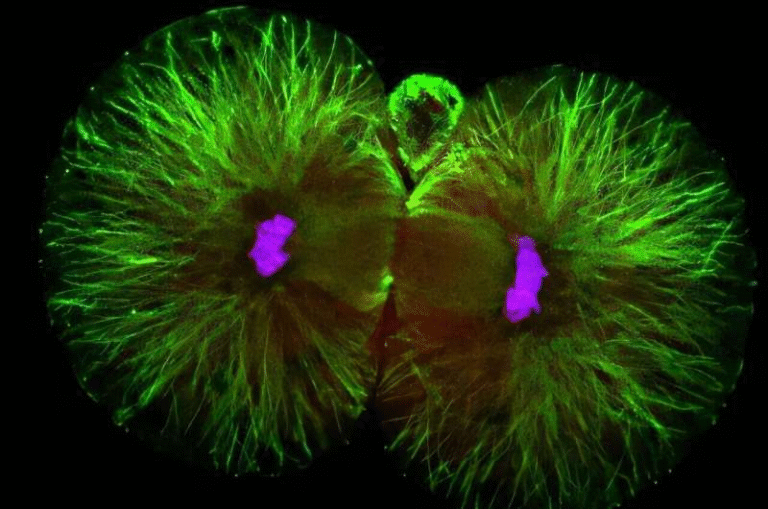

Even though corals do not have eyes, they can still sense light. They do this using rhodopsins and opsins, the same types of light-sensitive proteins found in the rods and cones of human eyes. This sensory capability turned out to be central to the discovery.

Opsin Genes and the Birth of New Coral Species

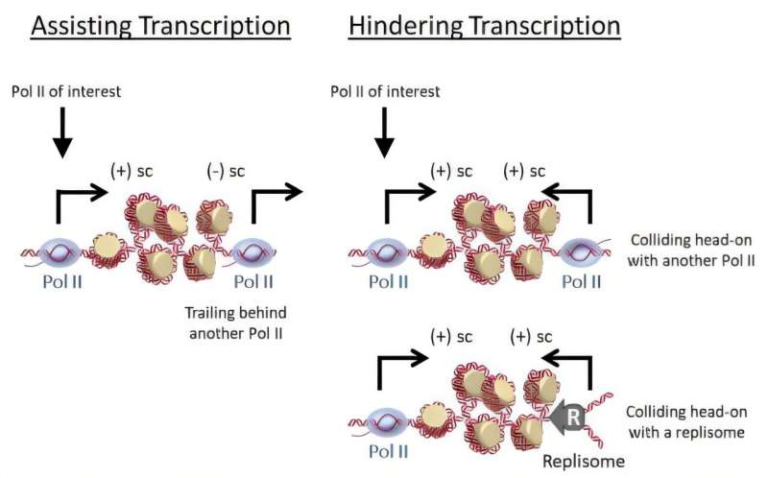

The researchers found that opsin genes, which play a key role in light detection, are under strong natural selection in corals living at different depths. Changes in these genes alter how corals perceive light cues from their environment.

This matters because coral reproduction is tightly synchronized with environmental signals. Moonlight, temperature changes, and specific light wavelengths all help determine when corals spawn. If two coral populations interpret these cues differently, they may release their gametes at different times—even if they live close to one another.

That timing difference creates reproductive isolation, one of the most important steps in the formation of new species.

A Close Look at Caribbean Reef Corals

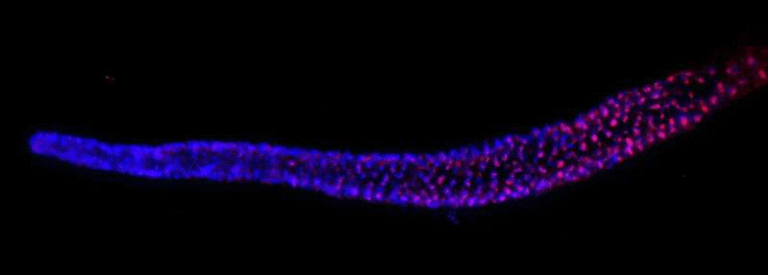

To test this idea, Gómez-Corrales and Prada focused on a well-known Caribbean reef-building coral, Orbicella faveolata. This species complex includes closely related lineages that occupy different depths, sometimes separated by less than 20 meters of water.

Using genomic data from coral colonies collected in Puerto Rico, Panama, Mexico, and Florida, the team showed that these lineages diverged roughly 212,000 years ago. Despite the small geographic separation, shallow and deep populations were genetically distinct.

Crucially, the strongest genetic differences were not scattered randomly across the genome. Instead, they were concentrated in genes associated with environmental sensing and phototransduction, including opsins and other proteins involved in light perception.

Environmental Sensing as a Driver of Reproductive Isolation

The study revealed that genome differentiation between shallow and deep coral lineages is driven mainly by proteins involved in responding to environmental cues. These proteins influence signaling pathways that regulate coral reproductive cycles.

Coral spawning is known to depend on a combination of light cues, neuropeptides such as dopamine, and temperature changes. When these signals excite light receptors in coral tissue, they trigger coordinated reproductive events. If corals at different depths perceive these signals differently due to changes in opsin gene expression, their spawning times can shift just enough to prevent interbreeding.

This mechanism allows corals to evolve new species through ecological speciation, where adaptation to different environments directly causes reproductive isolation.

A Pattern Seen Across the Ocean

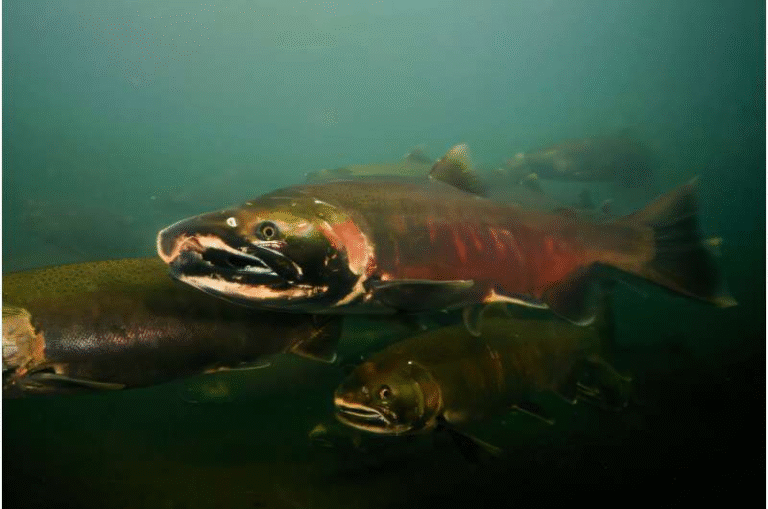

What makes this discovery particularly compelling is that similar mechanisms appear across many marine organisms. The researchers note parallels with fish, jellyfish, and sea anemones, where light, temperature, and neuropeptide signaling also regulate reproduction.

In fish, for example, single amino acid changes in opsin genes have repeatedly evolved in species adapted to different light conditions, such as those living in red-shifted or blue-shifted environments. The new coral study suggests that parallel divergence driven by light perception may be a widespread engine of marine biodiversity.

Expanding an Existing Hypothesis

Carlos Prada had previously proposed that coral speciation often occurs as a result of depth-related ecological adaptation. Over the past two decades, this idea has gained support from studies in plants, insects, and vertebrates. What had been missing was a clear understanding of the molecular mechanisms that link environmental adaptation to reproductive isolation.

This study fills that gap by showing how genes involved in phototransduction and environmental sensing can fine-tune reproductive timing, ultimately leading to speciation.

Why This Matters for Coral Reefs and Climate Change

Understanding how new coral species form is not just an academic exercise. Coral reefs are under severe threat from ocean warming, light stress, and climate-driven changes in water clarity. Knowing how corals adapt—or fail to adapt—to changing light environments can help scientists predict which species are more likely to survive.

The findings also have implications for coral conservation and restoration efforts. If light perception and environmental sensing play a central role in coral reproduction, restoration projects may need to consider depth-specific adaptations when relocating or breeding corals.

A Broader View of Ocean Biodiversity

This research helps explain how extraordinary biodiversity can arise in the ocean without obvious physical barriers. By linking light, gene evolution, and reproductive isolation, the study offers a powerful framework for understanding how marine species diversify across seemingly continuous environments.

As Gómez-Corrales has noted, there is a striking gap between the immense diversity found on coral reefs and our limited understanding of how that diversity is generated and maintained. Studies like this provide essential tools for closing that gap and protecting reefs for the future.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65226-9