Scientists Finally Explain How Damaged Tissue Regenerates After Massive Cell Death

For decades, biologists have known something strange and remarkable: certain tissues can regenerate even after experiencing extreme damage that kills large numbers of cells. This ability, called compensatory proliferation, was first observed in the 1970s when fruit-fly larvae managed to regrow fully functional wings after being blasted with high doses of radiation. The phenomenon has since been documented in many organisms, including humans, yet the underlying molecular mechanism remained a mystery for nearly 50 years.

Now, a new study from the Weizmann Institute of Science, published in Nature Communications, finally explains how this regenerative comeback works. The researchers discovered that the very enzymes responsible for triggering cell death can also help some cells survive, multiply, and rebuild damaged tissue. Even more intriguingly, the same mechanism may help explain why some cancers return stronger and more resistant after radiation therapy.

What Is Compensatory Proliferation?

Compensatory proliferation refers to a process in which tissues respond to widespread cell death by rapidly increasing cell division to replace what was lost. This isn’t just routine healing; it happens after severe damage, such as exposure to high levels of ionizing radiation.

Epithelial tissues—those that line organs and cover surfaces like skin—are particularly good at this. These tissues are constantly exposed to environmental stress, so evolution appears to have equipped them with backup systems to ensure survival even when destruction is widespread.

Despite decades of observation, scientists didn’t know which cells were responsible for driving this regrowth or how they managed to survive conditions that killed their neighbors.

Caspases: More Than Just Executioners

At the heart of the discovery are caspases, enzymes best known for their role in apoptosis, or programmed cell death. Normally, apoptosis is a carefully controlled process that removes damaged or unnecessary cells. It begins when an initiator caspase activates and then triggers effector caspases, which dismantle the cell from the inside.

Over the past 20 years, however, researchers—including Prof. Eli Arama of Weizmann’s Molecular Genetics Department—have shown that caspases aren’t limited to killing cells. They also play roles in development, cell signaling, and tissue remodeling.

This led to a bold idea: what if caspases were also involved in compensatory proliferation?

Recreating a Classic Experiment With Modern Tools

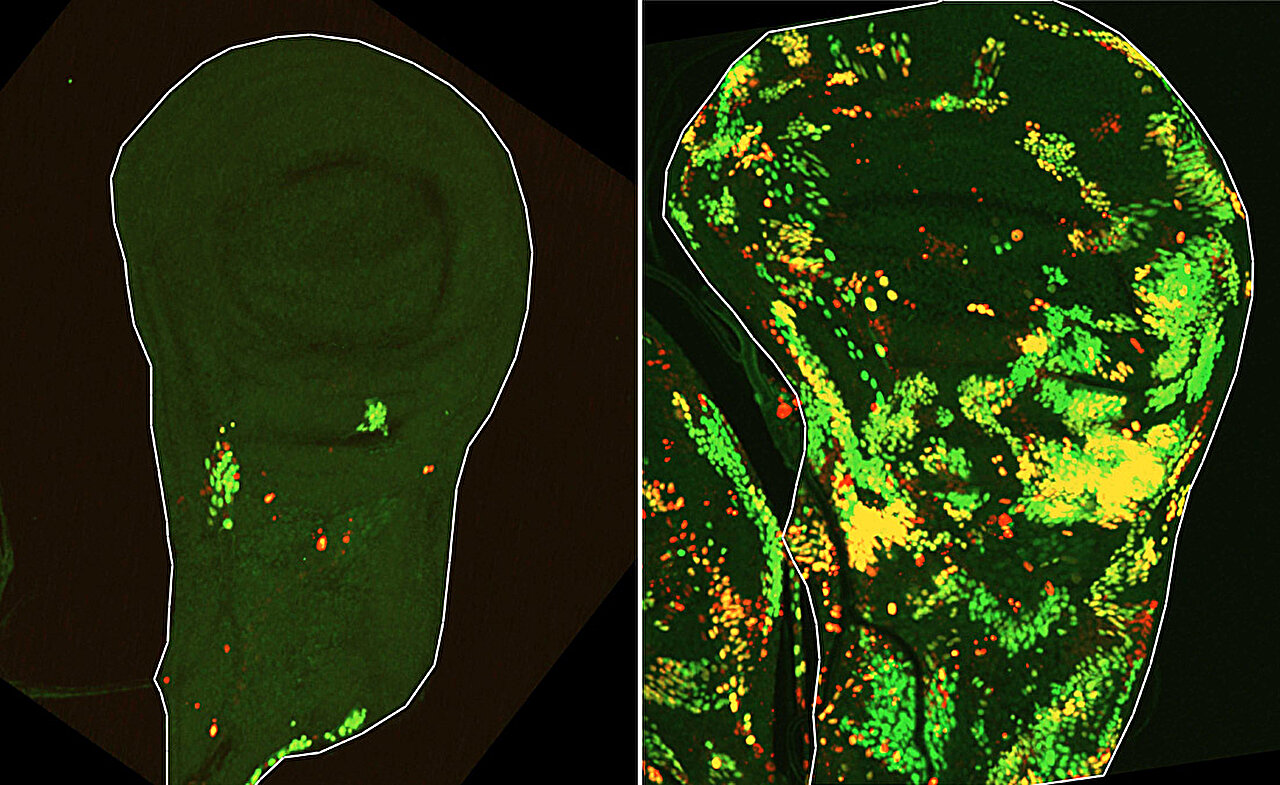

To test this idea, a team led by Dr. Tslil Braun repeated the original radiation experiments using fruit-fly larvae. This time, they used advanced genetic tracking tools that allowed them to observe exactly which cells activated apoptotic pathways and what happened to them afterward.

What they found was surprising. Some cells activated the initiator caspase—the signal that normally starts apoptosis—but did not die. Instead, they survived, multiplied, and played a central role in rebuilding the damaged tissue.

These cells were named DARE cells, short for Death-Activated but Resistant to Execution.

DARE Cells and Their Crucial Role

DARE cells are unusual because they sit right on the edge between life and death. They activate the first step of apoptosis but somehow block the process before it becomes fatal. After radiation damage, the number of DARE cells peaks around 24 hours, and over the next day, their descendants repopulate nearly half of the damaged tissue.

When researchers experimentally removed DARE cells, compensatory proliferation failed entirely. This showed that while other cells may assist in regeneration, DARE cells are absolutely essential for the process to occur.

The Supporting Cast: NARE Cells

The study also identified a second group of cells called NARE cells—Non-Activated but Resistant to Execution. Unlike DARE cells, these cells do not activate the initiator caspase at all, yet they also survive radiation-induced damage.

NARE cells contribute to regeneration, but they cannot initiate it on their own. Without DARE cells, NARE cells are unable to drive tissue repair. This revealed a cooperative system in which different populations of death-resistant cells work together, each with a distinct role.

How DARE Cells Cheat Death

The next question was obvious: how do DARE cells survive when their neighbors die?

The researchers discovered that while the initiator caspase is activated in DARE cells, the signal does not progress to effector caspases. This interruption prevents the cell from being dismantled.

The key player appears to be a molecular motor protein that tethers the initiator caspase to the cell membrane. By anchoring it in place, the motor protein prevents the cascade that would normally lead to cell death.

When this motor protein was silenced, DARE cells died, and tissue regeneration was severely impaired. Notably, overactivation of similar motor proteins has previously been linked to tumor growth, hinting at a deeper connection between regeneration and cancer.

Signals From Dying Cells Matter

Another important finding is that dying cells are not just passive victims. Signals released by apoptotic cells actively help activate DARE cells, triggering the regenerative response. This shows that tissue repair is not driven by survivors alone but is a coordinated response involving both dying and surviving cells.

Regeneration Comes With a Cost: Cancer Resistance

One of the most striking results came when researchers irradiated the same tissue a second time. During the first few hours after re-irradiation, only half as many cells died compared to the initial exposure.

Most of the cells that did die belonged to the NARE population. Descendants of DARE cells were found to be seven times more resistant to apoptosis than cells in the original tissue.

This finding may help explain a long-standing clinical problem: tumors that recur after radiation therapy often become more aggressive and harder to kill. If cancer cells exploit the same mechanisms as DARE cells, they may inherit enhanced resistance to cell death.

Preventing Runaway Growth

Regeneration must be carefully controlled. Too little growth leads to failed repair; too much leads to tumors. The study uncovered a negative-feedback loop that keeps this balance in check.

DARE cells promote the proliferation of nearby NARE cells by secreting growth signals. In response, NARE cells send inhibitory signals that limit DARE cell growth. This two-way communication prevents excessive tissue expansion while still allowing effective repair.

Why Fruit Flies Matter to Human Health

Fruit flies may seem far removed from human biology, but epithelial tissues in flies and humans share many molecular pathways. Many cancers—including skin, colon, and lung cancers—originate in epithelial cells.

Understanding how normal tissues balance regeneration and growth resistance may provide crucial insights into why apoptosis-based cancer treatments sometimes fail and how they could be improved.

What This Means for the Future

This study solves a half-century-old mystery and opens several new research directions. It suggests ways to accelerate wound healing, improve tissue regeneration after injury, and potentially prevent cancer relapse by targeting death-resistant cell populations.

It also reinforces a broader lesson in biology: molecules rarely have a single role. Enzymes designed to kill cells can, under the right conditions, become powerful tools for survival and renewal.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65996-2