Predictive Mismatch Leads to a Novel Carbon Capture Method and a Smarter Way to Design Materials

When experiments don’t line up with predictions, scientists usually assume the models were wrong and move on. But a new study in carbon capture research shows that these so-called mismatches can actually be the most valuable clues of all. Instead of signaling failure, the gap between theory and experiment led researchers to uncover a hidden problem—and ultimately a new, more effective way to design carbon-capturing materials.

The research, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS) and selected as an Editor’s Choice, focuses on advanced materials known as covalent organic frameworks, or COFs. These materials are already considered promising candidates for pulling carbon dioxide directly from the air, but they come with a stubborn challenge: water.

Understanding the Problem with Carbon Capture Materials

Capturing carbon dioxide from ambient air is far more difficult than trapping it from industrial exhaust. CO₂ concentrations in the atmosphere are low, and humidity is high. Many materials that work well under dry lab conditions struggle once water molecules enter the picture.

COFs are crystalline, porous materials built from carefully designed molecular building blocks. Their defining feature is a network of uniform nanoscale pores with extremely high internal surface area. These pores can be chemically tuned to attract specific gases like CO₂ or methane, making COFs highly attractive for environmental applications.

For years, researchers believed they had a solid understanding of how certain COFs behave. But when a specific material called COF-999-NH₂, a precursor to COF-999, was tested, things didn’t add up.

When Predictions and Experiments Didn’t Match

A team led by Prof. Laura Gagliardi at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, working with Prof. Omar Yaghi at the University of California, Berkeley, set out to model COF-999-NH₂ using advanced computational simulations. These models predicted how the material should behave structurally and how efficiently it should capture CO₂.

But when experimental results came back, they didn’t align with the predictions. CO₂ uptake and structural features differed from what the simulations suggested.

Instead of discarding the theoretical work, the researchers took a different approach. They treated the mismatch itself as meaningful data.

This decision proved crucial.

Residual Water Was the Missing Piece

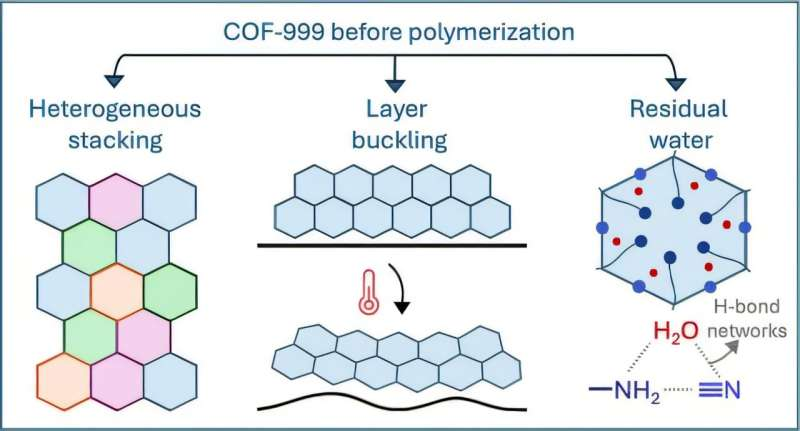

Through close collaboration between computational scientists and experimental chemists, the team began to suspect something subtle but important: residual water molecules were still present inside the COF, even though the material was believed to be fully dehydrated.

Water molecules, it turned out, were quietly occupying the pores of the framework. These molecules blocked CO₂ adsorption sites and triggered unexpected structural changes. Because the original simulations assumed a completely dry material, they failed to capture this effect.

Once water was included in the models, the mismatch disappeared.

This discovery reshaped how researchers understand COF behavior under real-world conditions, where humidity is unavoidable.

A Simple Design Rule with Big Impact

The most important outcome of the study was the creation of a clear, actionable design rule for future carbon capture materials: control pore hydrophobicity during polymerization.

By making the internal pores of COFs more hydrophobic, researchers can prevent water from being retained inside the structure. This keeps adsorption sites open, avoids unwanted chemical side reactions, and significantly improves CO₂ capture performance.

Rather than fighting water after the material is made, this approach addresses the problem at the design stage—an elegant and practical solution.

Unexpected Structural Insights

While investigating the water issue, the researchers uncovered additional insights about COF-999-NH₂ that had not been fully understood before.

They observed stacking heterogeneity, layer buckling, and lattice contraction within the material. These features might normally be labeled as defects, but the study revealed that they are actually intrinsic characteristics of the precursor chemical itself.

Recognizing these traits as inherent, rather than accidental, allows scientists to model COFs more accurately and design future frameworks with fewer surprises.

Why Computational Modeling Matters More Than Ever

This work highlights the growing importance of computational modeling in modern materials science. Simulations are no longer just tools for prediction; they are powerful engines for discovery.

By exploring countless scenarios on a computer—including ones that might not seem intuitive—researchers can uncover hidden factors that experiments alone might miss. In this case, simulations helped identify water as the culprit and guided the team toward a better design strategy.

The study makes a strong case that disagreement between theory and experiment is not a setback, but a starting point for deeper understanding.

The Broader Context of Direct Air Capture

Direct air capture (DAC) is gaining attention as a potential tool for addressing climate change. Unlike point-source capture, DAC can remove CO₂ already circulating in the atmosphere. However, it demands materials that are selective, durable, and efficient under humid conditions.

COFs are particularly attractive for DAC because they are:

- Highly tunable at the molecular level

- Structurally ordered and crystalline

- Capable of repeated adsorption and release cycles

- Chemically customizable for specific gases

The insights from this study push COFs closer to real-world deployment by tackling one of their biggest weaknesses: water interference.

The Role of Collaborative Research

This research emerged from The Center for Advanced Materials for Environmental Solutions (CAMES), a joint initiative connected to the University of Chicago Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth. The project reflects a broader goal of translating laboratory discoveries into technologies with real environmental impact.

The collaboration between theoretical chemists, experimental scientists, and materials engineers was essential. Without close coordination, the predictive mismatch might have been dismissed rather than explored.

A Timely Moment for COF Research

Interest in COFs and reticular chemistry has surged recently, especially following Omar Yaghi’s recognition with the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, alongside Susumu Kitagawa and Richard Robson. Their work laid the foundation for designing extended crystalline frameworks with atomic-level precision.

This new study builds directly on that legacy, showing how detailed molecular design can solve practical environmental challenges.

What This Means Going Forward

The takeaway from this research is refreshingly straightforward: materials must be designed for the conditions they will actually face, not idealized lab environments. By embracing predictive mismatches instead of ignoring them, scientists can uncover hidden variables and make smarter materials.

For carbon capture, that means frameworks that repel water, maintain open pores, and perform consistently in the real atmosphere.

It’s a reminder that progress in science often comes not from perfect predictions, but from paying close attention when things don’t go as expected.

Research Paper Reference:

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.5c18608