Anything-Goes Anyons May Explain Why Superconductivity and Magnetism Are Showing Up Together

In the past year, physicists have been confronted with an unexpected and fascinating puzzle. Two independent experiments, carried out in entirely different materials, observed something long thought to be impossible: superconductivity and magnetism existing side by side. For decades, textbooks confidently stated that these two quantum states should destroy each other. Yet nature, once again, appears to have other plans.

Now, theoretical physicists at MIT believe they may have found an explanation. Their work suggests that the key players behind this surprising behavior could be exotic quantum entities known as anyons. If their theory is correct, it points to an entirely new form of superconductivity—one that not only survives magnetism but may actually depend on it.

Why Superconductivity and Magnetism Were Thought to Be Enemies

To understand why this discovery is so striking, it helps to revisit some basics.

Superconductivity occurs when electrons inside a material pair up into so-called Cooper pairs and flow without resistance. This frictionless motion allows electric currents to travel indefinitely, making superconductors incredibly useful for technologies like MRI machines, particle accelerators, and quantum computers.

Magnetism, on the other hand, arises when electrons align their spins or orbital motion in a coordinated way, creating a magnetic field. The problem is that magnetic fields tend to disrupt Cooper pairs. Even weak magnetism can usually break these fragile electron partnerships apart.

Because of this, physicists long assumed that a material could not be both magnetic and superconducting at the same time. That assumption held up for decades—until recently.

Two Experiments That Changed the Conversation

The first experimental surprise came from work on rhombohedral graphene, a specially stacked form of graphene made from four or five layers of carbon atoms. Researchers found that this material displayed both magnetism and superconductivity under the same conditions. The result stunned the condensed-matter physics community and raised immediate questions about what mechanism could allow such a contradiction.

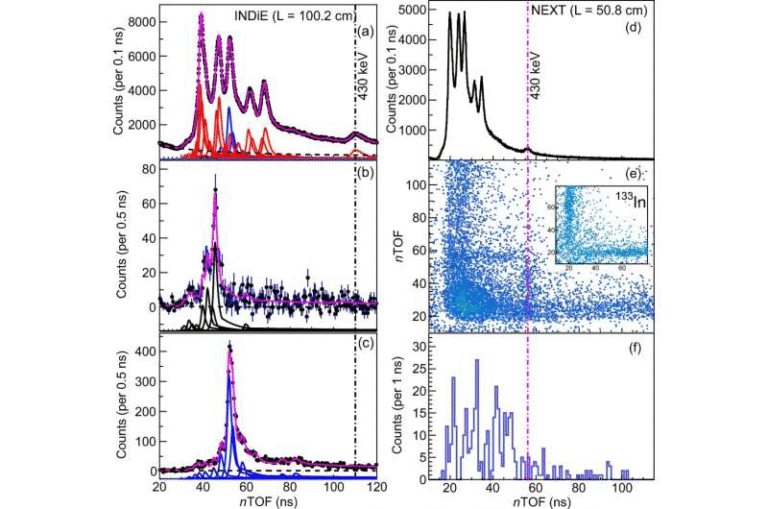

Soon after, a second experiment deepened the mystery. Scientists studying the semiconducting crystal molybdenum ditelluride (MoTe₂) observed the same unlikely coexistence. Even more intriguingly, the superconducting phase appeared under conditions where the material also showed a phenomenon called the fractional quantum anomalous Hall effect, or FQAH.

This detail turned out to be crucial.

Enter Anyons, the Oddballs of the Quantum World

The fractional quantum anomalous Hall effect is a strange state of matter in which electrons effectively split into smaller pieces. These pieces behave like independent quasiparticles known as anyons.

Anyons are fundamentally different from the familiar particles that make up our universe. Most particles fall into one of two categories: fermions, such as electrons, protons, and neutrons, which avoid each other, and bosons, such as photons, which like to pile together. Anyons belong to a third category altogether.

What makes anyons especially unusual is that they exist only in two-dimensional systems. When two anyons exchange positions, the quantum state of the system changes in a way that is neither fermionic nor bosonic. This strange behavior is why physicist Frank Wilczek famously gave them a playful name that suggests “anything goes.”

Anyons were first predicted in the 1980s, and soon after, theorists proposed that under the right conditions, they could form superconducting states—especially in the presence of magnetism. The problem was that no one could find a real material where this idea made sense. Until now.

Revisiting an Old Idea with New Evidence

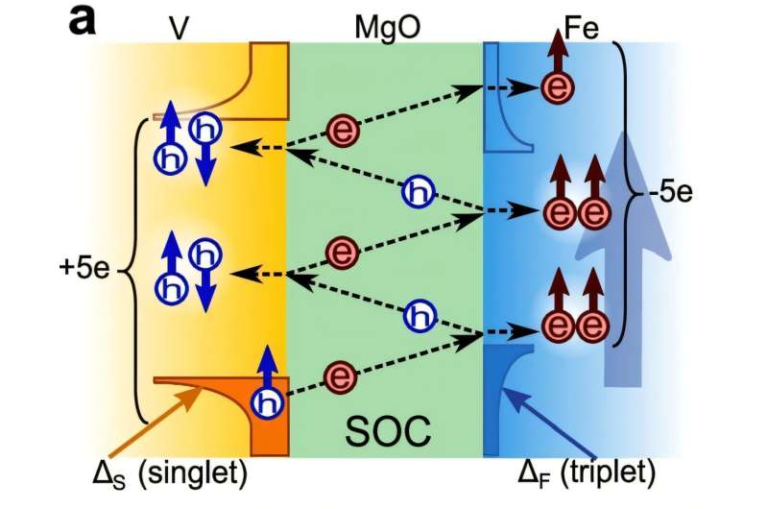

Motivated by the MoTe₂ experiments, MIT physicists Senthil Todadri and Zhengyan Darius Shi revisited these older theories with modern tools. Using quantum field theory, they set out to determine whether superconducting anyons could realistically emerge in a two-dimensional material that also hosts magnetism.

Anyons are notoriously difficult to work with, even theoretically. Each anyon’s motion is affected by every other anyon in the system, no matter how far apart they are. This leads to a kind of quantum “frustration” that usually prevents them from flowing smoothly together.

Despite this, Todadri and Shi identified specific conditions under which anyons could escape this frustration and behave collectively, forming a superconducting state.

Why the Fraction of Charge Matters

Their calculations revealed an important detail: not all anyons behave the same way.

In MoTe₂, electrons can fractionalize into anyons carrying either one-third or two-thirds of an electron’s charge. When one-third–charged anyons dominate, the system behaves like an ordinary metal. The anyons remain frustrated and resist forming a coherent flow.

But when two-thirds–charged anyons become dominant, something remarkable happens. These anyons can move together without resistance, creating a superconducting state that closely resembles conventional superconductivity—but with a completely different microscopic origin.

In this picture, superconductivity does not arise from paired electrons. Instead, it emerges from the collective motion of fractionalized anyons.

A New Kind of Superconducting Behavior

The theory also predicts experimental signatures that could help confirm whether superconducting anyons are truly responsible. One striking prediction is that superconductivity would initially appear as swirling supercurrents forming spontaneously at random locations throughout the material.

This behavior is fundamentally different from what physicists see in ordinary superconductors and could provide a clear way for experimentalists to test the theory.

If verified, this would represent an entirely new mechanism for superconductivity, one that coexists naturally with magnetism rather than being destroyed by it.

What This Means for Quantum Materials

The implications of this work extend far beyond MoTe₂ or graphene.

If superconducting anyons can be confirmed and controlled, physicists would be looking at a new category of matter sometimes referred to as anyonic quantum matter. Such materials could host rich and unexpected quantum phases that are impossible in conventional three-dimensional systems.

Perhaps most exciting is the potential connection to quantum computing. Anyons have long been proposed as building blocks for stable qubits because their exotic properties make them resistant to environmental noise. A superconducting state built from anyons could provide new pathways for designing robust quantum hardware.

Why This Discovery Matters

At its core, this research challenges a deeply held assumption in physics. The idea that superconductivity and magnetism must always oppose each other may not be a universal rule after all. Instead, nature appears to allow clever workarounds—especially when electrons are allowed to split into more exotic forms.

While many experiments are still needed to confirm this theory, the possibility that fractional particles could carry superconducting currents opens a new chapter in the study of quantum matter.

If nothing else, it serves as a reminder that even well-established scientific “rules” are always subject to revision when new evidence comes along.

Research Paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2520608122