Why a Chiral Magnet Acts Like a One-Way Street for Electrons

Physicists at Japan’s RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science have uncovered something researchers have been puzzling over for years: why electrons flow more easily in one direction than the other inside a single magnetic material. This strange behavior, found in a special class of materials known as chiral magnets, could play an important role in the future of low-energy electronic and spintronic devices.

The findings, published in Science Advances, are significant because they don’t just observe the effect — they finally explain what causes it, and why different mechanisms dominate under different conditions.

What Makes Chiral Magnets Different from Ordinary Magnets

In a conventional magnet, electron spins tend to align neatly in the same direction. This uniform alignment gives rise to familiar magnetic behavior, such as attraction and repulsion.

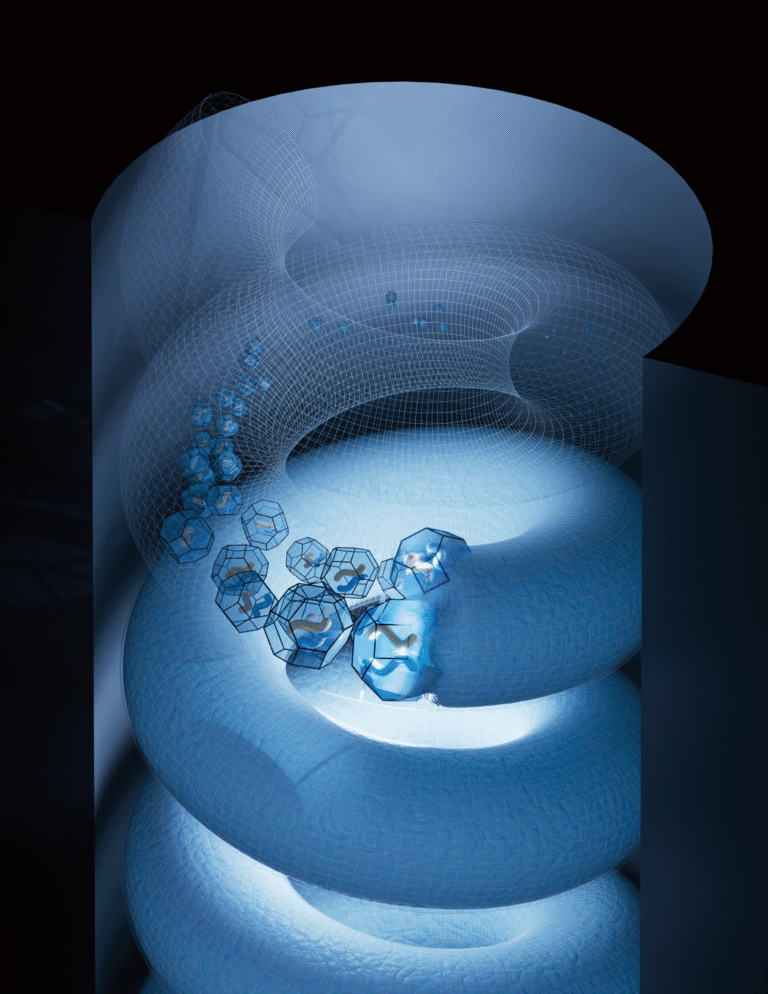

Chiral magnets, however, behave very differently. Instead of lining up straight, the spins of their electrons form a helical or spiral pattern, often compared to a twisted staircase. This helical structure breaks certain symmetries inside the material, and that turns out to be crucial.

Because of this broken symmetry, chiral magnets can show nonreciprocal electron transport. In simple terms, electrons prefer moving one way over the opposite direction, even though they are traveling through the same material. This effect resembles what happens in a diode, but with a key difference: it occurs inside a single, uniform material rather than at a junction between two different semiconductors.

Why Direction-Dependent Electron Flow Matters

Direction-dependent transport is not just a scientific curiosity. It has real technological implications. Devices that allow electrons to flow preferentially in one direction are essential in electronics, especially for rectification, signal control, and energy efficiency.

What makes chiral magnets particularly exciting is that they can achieve this behavior without complex layered structures or interfaces. That opens the door to simpler, more robust, and potentially lower-energy devices.

Chiral magnets are also known for hosting skyrmions, which are tiny, stable magnetic whirlpools. Skyrmions are widely studied because they could be used to store and process information using very little energy, making them promising candidates for next-generation memory technologies.

The Longstanding Mystery Researchers Wanted to Solve

For years, scientists have proposed multiple theories to explain why electrons behave nonreciprocally in chiral magnets. However, there was a problem. While experiments showed the effect clearly, no study had managed to separate and directly identify the different mechanisms contributing to it within a single material.

This gap in understanding made it difficult to fully control or optimize the phenomenon for practical use. According to the RIKEN researchers, identifying the precise mechanisms was essential if scientists wanted to move beyond observation and toward engineering applications.

The Material at the Center of the Study

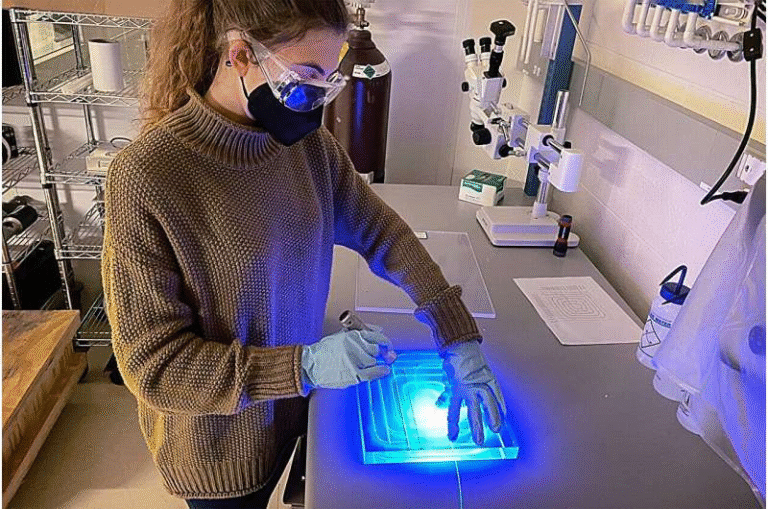

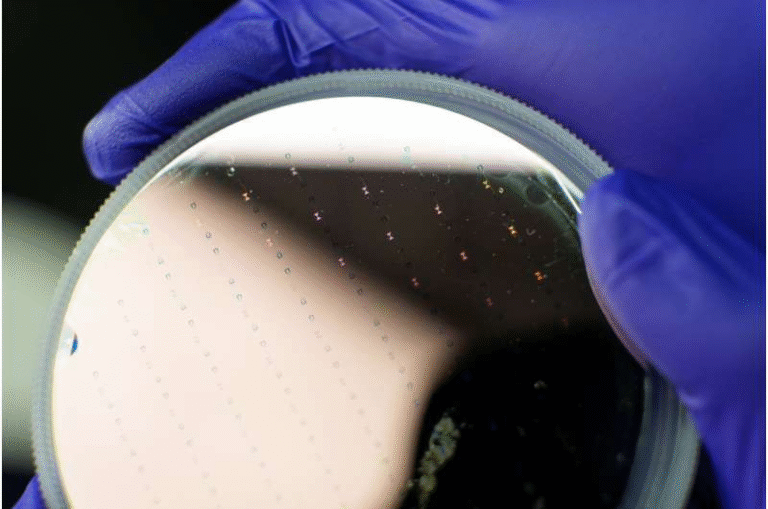

To tackle this challenge, the research team focused on a chiral magnet made from cobalt, zinc, and manganese, with the chemical composition Co₈Zn₉Mn₃.

This particular material was chosen for an important reason. Unlike many chiral magnets, which only show helical spin structures at very low temperatures, Co₈Zn₉Mn₃ maintains its chiral magnetic order across a wide temperature range, including room temperature. That makes it especially relevant for real-world applications.

Two Distinct Mechanisms Behind One-Way Electron Flow

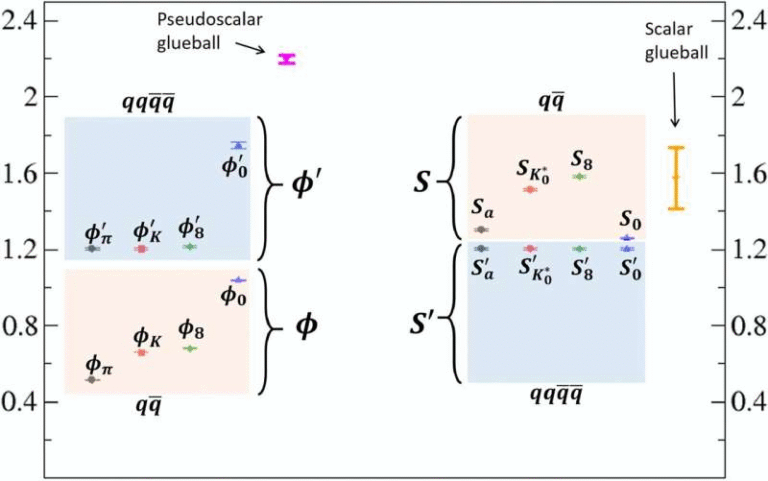

The most important breakthrough of the study is the discovery that two separate physical mechanisms are responsible for the direction-dependent flow of electrons. Which mechanism dominates depends on temperature and magnetic field conditions.

1. Chiral Scattering by Magnetic Quasiparticles

In certain temperature and magnetic field ranges, electrons moving through the material interact with magnetic quasiparticles that possess chirality. These quasiparticles act like obstacles that scatter electrons.

Crucially, the scattering is direction-dependent. Electrons traveling in one direction collide more frequently with these chiral excitations, while electrons moving in the opposite direction experience fewer scattering events. The result is an imbalance in electrical resistance depending on direction.

This mechanism highlights how dynamic magnetic fluctuations inside the material can strongly influence electron transport.

2. Asymmetric Energy Landscape from Helical Spin Coupling

The second mechanism comes into play through the interaction between mobile electrons and the static helical spin structure of the magnet.

Because the background spins are arranged in a spiral pattern, they create a symmetry-breaking energy landscape for electrons. This alters the electronic band structure in such a way that moving forward is not energetically equivalent to moving backward.

In this case, the direction-dependent behavior does not rely on scattering but instead on how electrons are coupled to the underlying magnetic texture. This mechanism becomes dominant under different temperature and field conditions than the first.

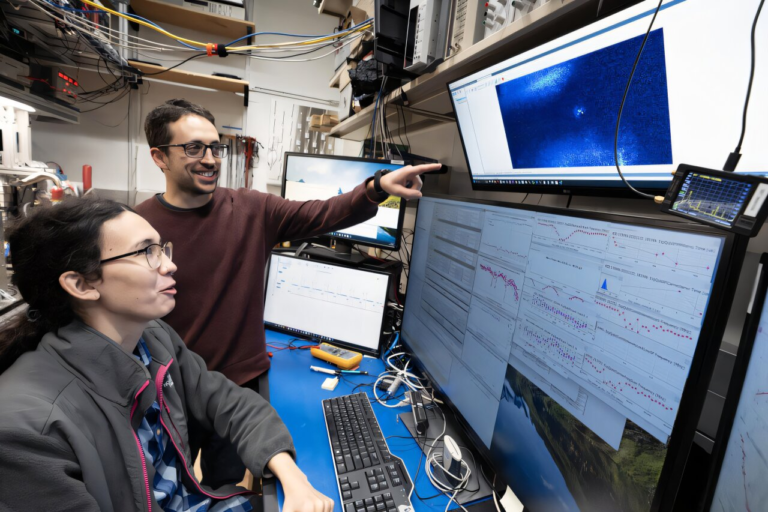

Why Theory Was Just as Important as Experiment

One of the key takeaways from the study is that experiments alone were not enough to identify these mechanisms. While measurements clearly showed nonreciprocal transport, they could not explain its origin by themselves.

To solve the puzzle, the experimental team collaborated closely with theoretical physicists, also based at RIKEN and partner institutions. Advanced theoretical calculations were needed to match experimental data with microscopic physical processes.

This combined approach allowed the researchers to confidently assign each contribution to its correct mechanism, something that had not been achieved before in a single chiral magnet system.

Broader Implications for Materials Science and Electronics

Although the study focused on Co₈Zn₉Mn₃, the researchers believe their findings are not limited to this one material. The same principles should apply to other chiral magnets and possibly even more complex magnetic systems.

Understanding how and why nonreciprocal transport occurs gives scientists a powerful new tool. With this knowledge, researchers can begin designing materials where one-way electron flow is tunable, controlled by temperature, magnetic field, or chemical composition.

Such control could be invaluable for future technologies, including spintronics, energy-efficient logic devices, and novel magnetic memory architectures.

What Comes Next for the Research Team

The next step for the researchers is to explore how changing the ratio of cobalt, zinc, and manganese affects the observed phenomena. By tweaking the material’s composition, they hope to fine-tune the balance between the two mechanisms and gain even greater control over electron transport.

This line of research could also reveal new chiral magnetic phases and unexpected electronic behaviors, further expanding the field.

A Clear Step Forward in Understanding Chiral Magnetism

This study represents a major advance in understanding nonreciprocal electrical transport. By clearly identifying and separating the underlying mechanisms, the RIKEN team has moved the field beyond speculation and into a more predictive, controllable phase.

For anyone interested in the future of low-energy electronics, magnetic materials, or fundamental condensed matter physics, this work provides a strong foundation for what comes next.

Research Paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adw8023