Ultrafast Fluorescence Pulse Technique Enables Imaging of Individual Trapped Atoms

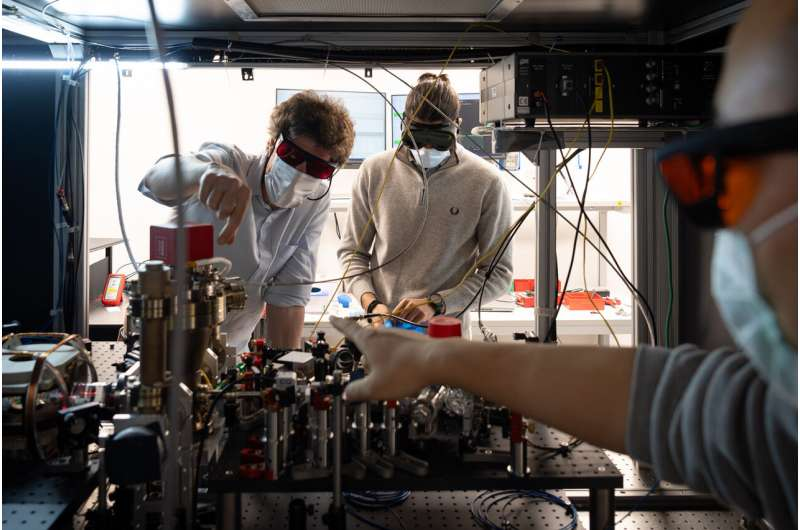

Researchers in Italy have reached an important milestone in atomic physics by successfully imaging individual trapped atoms at unprecedented speeds while keeping almost all of them intact. The work comes from a collaboration between the ArQuS Laboratory at the University of Trieste and the National Institute of Optics of the Italian National Research Council (CNR-INO), and it represents the first time individual trapped cold atoms have been imaged in Italy using this level of precision and efficiency.

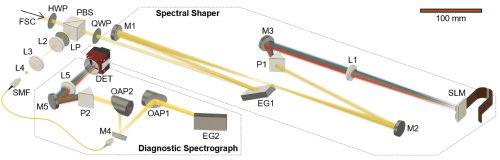

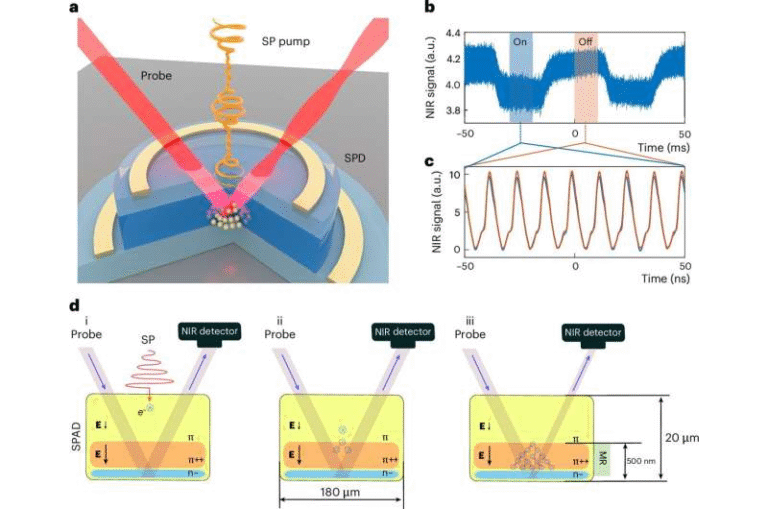

At the heart of this achievement is a new imaging strategy that replaces slow, long-exposure methods with intense ultrafast fluorescence pulses combined with rapid re-cooling techniques. Together, these approaches push single-atom detection into a completely new performance regime, opening the door to faster and more scalable quantum technologies.

A New Way to See Individual Atoms

Imaging single atoms has always been a delicate task. Atoms emit extremely faint light, and traditional imaging techniques rely on long exposure times to collect enough photons to separate the atomic signal from background noise. While effective, these long exposures come with drawbacks: they are slow, and they often heat the atoms enough to cause losses from the optical traps holding them in place.

The Italian research team took a different approach. Instead of waiting longer, they chose to illuminate atoms much more intensely but for only a few microseconds. This method is often compared to using a camera flash rather than leaving the shutter open for an extended period. In that very short time window, enough fluorescence photons are emitted to clearly detect each atom.

The result is remarkable. Individual ytterbium atoms can now be imaged in just a few microseconds, which is roughly a thousand times faster than typical acquisition times used in many current experiments.

Keeping Atoms Trapped and Reusable

Speed alone would not matter if the atoms were lost in the process. One of the most impressive aspects of this work is the extremely high survival rate of the atoms after imaging.

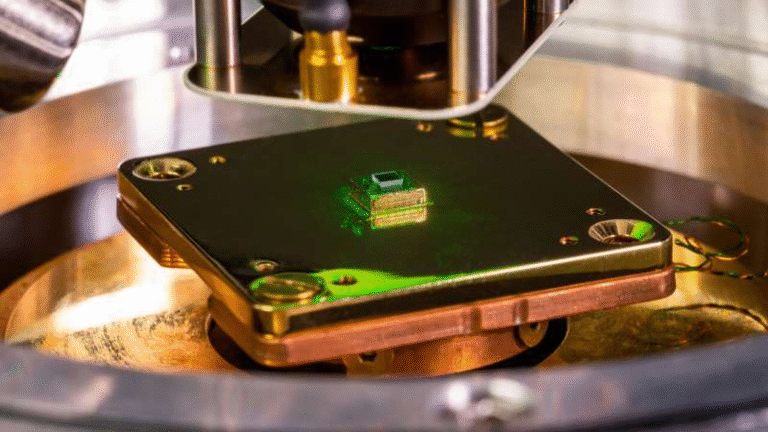

When atoms are illuminated intensely, they inevitably gain energy. Normally, this added energy would cause them to escape their optical traps. However, the researchers showed that with carefully timed, fast cooling pulses, this extra energy can be removed almost immediately. As a result, more than 99.5% of the atoms remain trapped after imaging and are ready for reuse.

This combination of high-speed detection and low atom loss makes the technique especially attractive for experiments that require repeated measurements on the same atomic system.

Counting Atoms, Not Just Detecting Them

Another major advance introduced by this technique is number-resolved detection. Many existing single-atom imaging methods can only tell whether an atom is present or not—essentially a binary “zero or one” measurement. This limitation becomes a serious obstacle as researchers try to scale up systems for quantum computing or simulation.

The ultrafast fluorescence pulse method allows scientists to distinguish multiple atoms within a single optical tweezer without significant blurring. In practical terms, this means researchers can count how many atoms are present on site, rather than just confirming their existence.

This capability is a key requirement for scaling neutral-atom quantum computers, where precise control over atom number directly affects computational accuracy and reliability.

First Imaging of Fermionic Ytterbium-173

Beyond speed and precision, the team also reported another first: the single-atom imaging of the fermionic isotope ytterbium-173.

Ytterbium-173 is particularly interesting because it has six internal ground-state levels, compared to the two levels typically used in standard qubit systems. This richer internal structure allows researchers to explore qudits instead of qubits. While a qubit stores information as 0 or 1, a qudit can store information in multiple states, potentially enabling more efficient quantum information storage and processing.

Successfully imaging single ytterbium-173 atoms is therefore an important step toward multi-level quantum circuits and more compact quantum architectures.

Why This Matters for Quantum Technology

The implications of this work extend far beyond a single experiment.

For neutral-atom quantum computers, fast and reliable atom detection is essential for initializing systems, correcting errors, and scaling up to larger arrays. The ability to image atoms quickly without losing them significantly reduces experimental downtime and improves overall system stability.

In next-generation atomic clocks, faster detection with minimal atom loss helps reduce dead time between measurements, which directly contributes to improved clock stability and precision.

For quantum simulators, especially those designed to explore complex many-body physics, number-resolved and repeatable imaging allows researchers to probe correlations and dynamics that were previously difficult or impossible to observe.

Optical Tweezers and Cold Atom Control

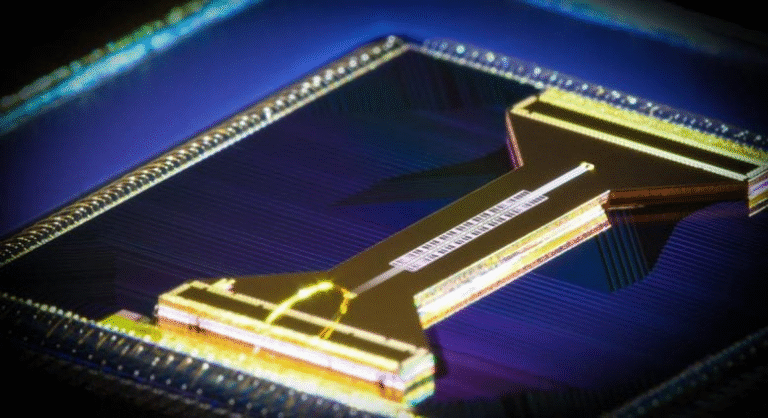

All of this work relies on optical tweezers, which are tightly focused laser beams capable of trapping individual atoms using light-matter interactions. Optical tweezers provide exceptional spatial control, allowing researchers to arrange atoms into precise geometries and manipulate them with high accuracy.

Cold atom platforms, particularly those based on alkaline-earth-like elements such as ytterbium, are attractive because of their long coherence times and relatively simple electronic structures. The new imaging technique complements these advantages by adding speed, precision, and reusability.

A Strong Contribution from Italian Research

This breakthrough highlights the growing role of Italian research groups in the global quantum science landscape. The ArQuS Laboratory, established through collaboration between the University of Trieste and CNR, has rapidly become a center for advanced research in ultracold atoms and quantum technologies.

Publishing results in leading journals such as Physical Review Letters and Quantum Science and Technology underscores the international relevance of this work and its potential to influence future experimental designs worldwide.

Looking Ahead

Ultrafast, low-loss imaging of individual atoms is more than just a technical improvement—it reshapes what is experimentally possible. By dramatically reducing imaging times while preserving atomic systems, this technique brings researchers closer to large-scale, practical quantum devices.

As quantum computing, simulation, and precision measurement continue to evolve, methods like this will likely become foundational tools, enabling experiments that demand both speed and control at the single-atom level.

Research Papers

Microsecond-Scale High-Survival and Number-Resolved Detection of Ytterbium Atom Arrays, Physical Review Letters (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.XXX.XXXX

Single-Atom Imaging of 173Yb in Optical Tweezers Loaded by a Five-Beam Magneto-Optical Trap, Quantum Science and Technology (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/adf7cf