Research Uncovers the Telltale Tail of Black Hole Collisions

When two black holes collide, the universe doesn’t just shake once and fall silent. It rings, settles, and then—very quietly—continues to murmur. A new study has now shown, in unprecedented detail, what that final murmur might look like. Known as late-time gravitational wave tails, these subtle signals have long been predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity but had never before been clearly captured in full, realistic simulations of black hole mergers.

Black holes themselves cannot be seen directly, even with the most advanced telescopes. Instead, scientists rely on gravitational waves, ripples in spacetime that are produced when massive objects like black holes accelerate or collide. Since the first detection of gravitational waves in 2015, researchers have been steadily improving their ability to decode these signals and understand what they reveal about the universe. This latest research adds an entirely new layer to that understanding.

The study was carried out by an international collaboration of 20 physicists, including researchers from the University of Mississippi (UM) and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Canada. Their findings were published in the journal Physical Review Letters in 2025. At the center of the work is a phenomenon that occurs after the main gravitational wave signal fades away.

When black holes merge, they produce a strong burst of gravitational waves followed by a phase known as the ringdown, where the newly formed black hole vibrates and rapidly settles into a stable shape. These vibrations are well understood and have been observed many times. But theory predicts that after the ringdown ends, spacetime should continue to respond very slowly, producing a weak, long-lasting signal—the late-time tail.

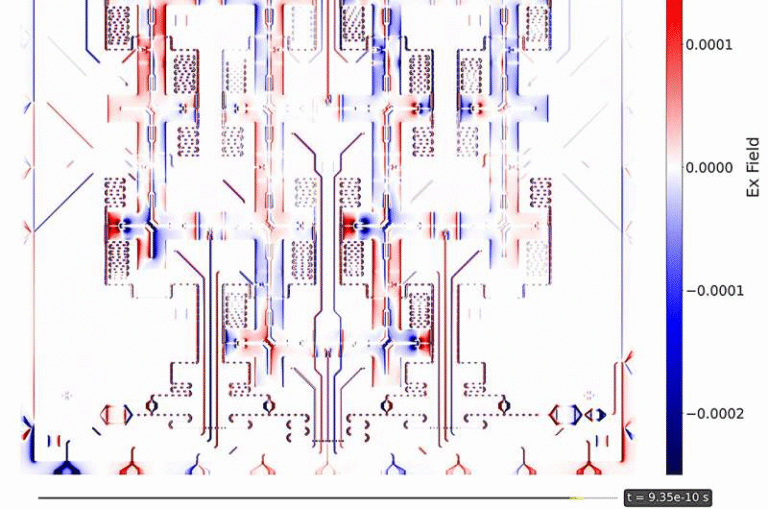

Until now, these tails had only been seen in simplified or approximate models. According to the researchers, this study marks the first time late-time tails have been clearly identified in fully nonlinear numerical relativity simulations, which solve Einstein’s equations in their full complexity. That distinction is crucial, because black hole mergers are among the most extreme and nonlinear events in the universe.

The simulations were led by Marina De Amicis, a postdoctoral researcher and fellow at the Perimeter Institute, with Leo Stein, an associate professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Mississippi, serving as a co-author. The team focused on understanding how spacetime behaves long after the loudest part of a black hole collision has passed.

Gravitational waves stretch and squeeze spacetime as they move outward. The late-time tail represents the slowest and faintest response of spacetime as it relaxes back toward equilibrium. Unlike the sharp, well-defined frequencies of the ringdown phase, these tails are not made up of a few distinct tones. Instead, they form a continuous spectrum of very low frequencies, often described as a low hum rather than a clear note.

This difference makes tails especially interesting from a scientific perspective. While the early part of a gravitational wave signal tells researchers about the small-scale physics close to the black holes, late-time tails are influenced by the large-scale structure of spacetime itself. In other words, they carry information not just about the black holes, but also about the vast regions of space the waves travel through.

Detecting these tails—whether in simulations or real data—is extremely challenging. They are weak, long-lasting, and easily drowned out by noise or other overlapping signals. To make the tails easier to identify, the researchers designed simulations that would make them as strong and “loud” as possible.

Instead of modeling the more common scenario where black holes spiral together in a nearly circular orbit, the team focused on highly eccentric, near head-on collisions. In these setups, the black holes crash together almost directly, producing a more violent interaction and a stronger gravitational wave tail. While such collisions are unlikely to be common in nature, they are ideal for studying the underlying physics.

The researchers are clear that this does not mean late-time tails will be easy to observe in real gravitational wave data anytime soon. Most black hole mergers detected by observatories like LIGO involve relatively circular orbits, which produce much weaker tails. However, having clear simulation results is a critical first step. Scientists now know what to look for and how these tails should behave if they appear in observational data.

These findings also provide another strong confirmation of general relativity. Late-time tails do not exist in flat spacetime; they arise only because spacetime is curved, as Einstein’s theory predicts. Observing or simulating them reinforces the idea that gravity is not just a force, but a manifestation of spacetime geometry itself.

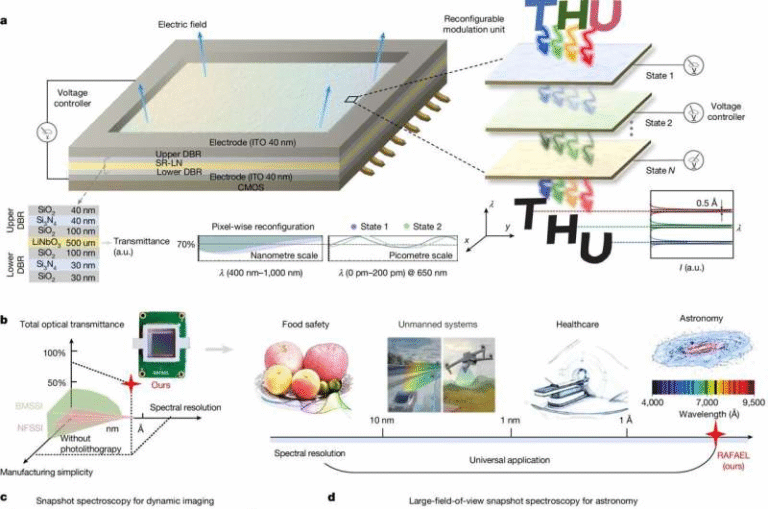

Gravitational waves were first predicted by Einstein in 1915, but it took a century of technological progress to detect them directly. Today, observatories such as LIGO on Earth and the planned space-based detector LISA rely heavily on theoretical models and simulations to interpret the signals they receive. The inclusion of late-time tails in these models could eventually help researchers test gravity in new ways and probe the universe on the largest scales.

The team’s work does not end here. Now that the basic “machinery” for detecting tails in simulations is in place, the next step is to make the models more realistic. Future simulations will reintroduce orbital motion and explore how tails behave in mergers that more closely resemble the black hole collisions we expect to see in the universe.

Understanding Gravitational Wave Tails in a Broader Context

Late-time gravitational wave tails have been discussed in theoretical physics for decades, particularly in studies of how waves scatter off curved spacetime. In simple terms, as gravitational waves travel outward, part of their energy can scatter off the curvature created by massive objects, feeding back into the signal at very late times. This effect is subtle, but it is a natural consequence of Einstein’s equations.

If future detectors become sensitive enough to measure these tails directly, they could provide new tests of gravity, help identify deviations from general relativity, or even offer clues about the structure of spacetime on cosmological scales. For now, simulations like this one are essential for building the foundation needed to make sense of any such observations.

What this study makes clear is that black hole collisions are not just brief cosmic fireworks. They are complex, multi-stage events whose effects linger far longer than we once realized. Even after the loud ringing fades, spacetime continues to whisper—and scientists are finally learning how to listen.

Research paper:

https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.XXX.XXXXX