Josephson Junction Behavior Observed With Only One Superconductor and an Iron Barrier

A fundamental building block of quantum technology has just been reimagined. Researchers have now confirmed that Josephson junction–like behavior can emerge even when only one superconductor is present, overturning a long-standing assumption in condensed matter physics and opening the door to simpler and more flexible quantum devices.

Traditionally, a Josephson junction requires two superconductors separated by a thin barrier. When arranged this way, superconductivity does something remarkable: the paired electrons responsible for lossless electrical flow can effectively “leak” into the barrier and synchronize the quantum behavior of both superconductors. This synchronized state is what allows Josephson junctions to play such a central role in quantum computing, precision sensing, and superconducting electronics.

In a newly published experimental study, however, an international team of scientists has shown that only one superconductor may be enough. Their measurements reveal electrical behavior that closely mimics a conventional Josephson junction—even though the second superconductor is missing.

What Makes a Josephson Junction So Important

Superconductivity arises when electrons form Cooper pairs, allowing current to flow without resistance. In a Josephson junction, these pairs tunnel through a thin insulating or metallic barrier between two superconductors. The result is a phase-locked system where current can flow even without an applied voltage, governed entirely by quantum mechanics.

Josephson junctions are not niche laboratory curiosities. They are core components of superconducting qubits, one of the most advanced and widely used platforms for quantum computers today. Improvements and extensions of Josephson-based technologies were even recognized with the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics, highlighting their scientific and technological importance.

Given this background, the idea that a Josephson-like effect could occur with only one superconductor has been discussed in theory for decades—but until now, it had never been convincingly demonstrated in the lab.

The Experimental Setup

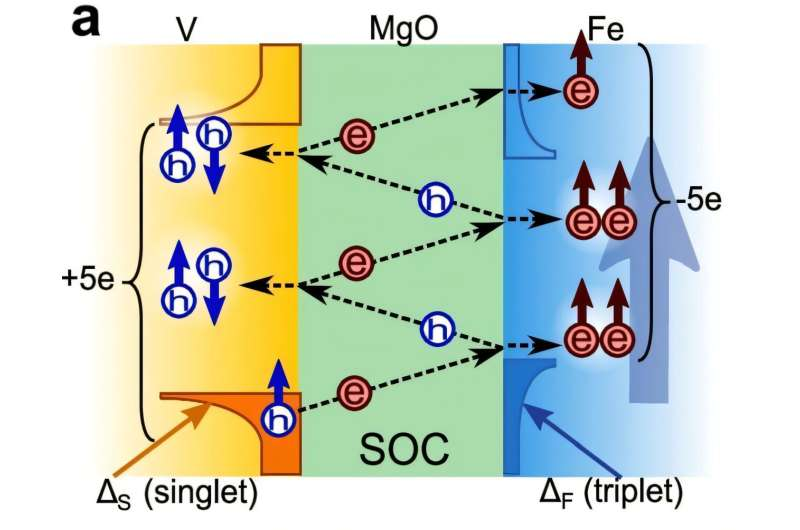

The device studied by the team was deceptively simple. It consisted of three layers:

- Vanadium, a well-known superconducting metal

- Magnesium oxide (MgO), acting as a thin insulating barrier

- Iron, a ferromagnetic metal

Under normal circumstances, iron should be the last material to display superconducting behavior. Ferromagnetism and superconductivity usually oppose each other, because superconducting Cooper pairs typically involve electrons with opposite spins, while ferromagnets strongly favor electrons with spins aligned in the same direction.

Despite this apparent incompatibility, the researchers observed that superconducting correlations from vanadium extended through the MgO barrier and into the iron layer. More importantly, these induced effects in iron were strong enough to produce electrical behavior nearly indistinguishable from that of a traditional Josephson junction.

How the Effect Was Detected

Instead of looking for conventional supercurrents alone, the team focused on a subtler signal: electrical noise, specifically a type known as shot noise.

Although electric current appears smooth at everyday scales, it is actually made up of discrete electrons arriving in tiny packets. The statistical fluctuations in this flow—its noise—can reveal how electrons move and whether they are acting independently or in coordinated groups.

In this experiment, the noise measurements showed something striking. Electrons in the iron layer were not moving randomly. Instead, they traveled in large, highly synchronized groups, a hallmark of superconducting pairing and Josephson-like coherence.

This kind of giant shot noise strongly suggested that iron was not just passively influenced by the nearby superconductor. It was actively participating in a coherent quantum process.

Same-Spin Electron Pairing in Iron

One of the most surprising outcomes of the study is the evidence for same-spin electron pairing inside the iron layer.

In conventional superconductors, Cooper pairs consist of electrons with opposite spins. Ferromagnets like iron disrupt this pairing by enforcing spin alignment. Yet in this system, iron appeared to generate a different kind of pairing—electrons with the same spin direction forming correlated pairs.

This effectively means that iron developed a distinct form of induced superconductivity, shaped by its magnetic nature but still able to synchronize with the vanadium superconductor across the barrier.

While the exact microscopic mechanism behind this robust pairing is still being investigated, the experimental data leave little doubt that iron played an active, coherent role rather than merely hosting weak, short-lived superconducting correlations.

Why This Discovery Matters

From a practical standpoint, the implications are significant.

First, simplifying Josephson junctions by reducing the number of superconducting components could make quantum devices easier to design and fabricate. Superconductors often require precise conditions and specialized materials, so minimizing their use is a major engineering advantage.

Second, the materials involved here—iron and magnesium oxide—are already widely used in commercial technologies, including magnetic hard drives and magnetic random-access memory (MRAM). Introducing superconducting functionality into such familiar materials could help bridge the gap between experimental quantum devices and scalable, real-world applications.

Connections to Topological Superconductivity

The discovery may also have deeper theoretical consequences. Same-spin electron pairing is closely connected to the concept of topological superconductivity, a highly sought-after state of matter in quantum science.

Topological superconductors are attractive because they can protect quantum information in a way that is inherently resistant to environmental noise. Instead of storing information in fragile local states, they encode it in global, “knot-like” properties of the system.

If same-spin pairing in ferromagnets can be reliably controlled and integrated into devices, it could offer new pathways toward more stable and fault-tolerant quantum computers.

A Long-Standing Theory Finally Confirmed

What makes this result particularly satisfying for physicists is that it confirms theoretical predictions made decades ago. Models had suggested that under the right conditions—especially involving spin-orbit coupling and carefully engineered interfaces—ferromagnets could host unconventional superconducting correlations.

This study provides the strongest experimental evidence so far that such ideas are not just mathematical curiosities but physically realizable phenomena.

The International Collaboration Behind the Work

The experiments were carried out in the laboratory of Farkhad Aliev at the Autonomous University of Madrid. The collaboration also included researchers from:

- The University at Buffalo (USA)

- Comillas Pontifical University (Spain)

- The University of Lorraine (France)

- Babeș-Bolyai University (Romania)

- The Eastern Institute for Advanced Study (China)

Theoretical interpretation and experimental design were closely intertwined, highlighting the importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration in modern physics.

Looking Ahead

Many questions remain. Scientists are still working to understand exactly how iron sustains such strong same-spin pairing and how broadly this phenomenon can be generalized to other materials and device architectures.

What is already clear, though, is that this experiment challenges a basic assumption about Josephson junctions and superconductivity. By showing that one superconductor can effectively create its own quantum partner, the study expands the toolkit available for quantum engineering and deepens our understanding of how superconductivity and magnetism can coexist.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64493-w