Stardust Study Resets How Life’s Atoms Spread Through Space

For decades, astronomers believed they had a solid understanding of how giant stars spread the elements needed for life across the galaxy. The idea was simple and elegant: as aging stars shed material, starlight pushes against newly formed dust grains, driving powerful stellar winds that carry atoms like carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen into interstellar space. These atoms later become part of new stars, planets, and eventually living systems.

A new study led by researchers at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden has now shown that this long-accepted explanation does not fully work. By closely observing the nearby red giant star R Doradus, scientists found that starlight and stardust alone are not strong enough to drive the stellar winds that distribute the building blocks of life through our galaxy. The findings significantly reshape how astronomers think about one of the most important processes in cosmic evolution.

Why Red Giant Stars Matter So Much

Red giant stars are aging stars that have exhausted most of the hydrogen fuel in their cores. Compared to stars like our Sun, they are larger, cooler, and far more unstable. During this late stage of stellar life, red giants lose huge amounts of material through stellar winds. These winds enrich the space between stars with heavy elements, often called “metals” in astronomy, which are essential for forming planets and organic molecules.

Without red giants, the universe would be far poorer in the raw materials needed for life. Understanding how these stars lose mass is therefore not just a technical problem—it connects directly to questions about how life-friendly environments emerge across the galaxy.

The Long-Standing Theory of Dust-Driven Winds

For many years, the dominant theory was that stellar winds from red giants are driven by radiation pressure. In this model, atoms in the star’s atmosphere condense into dust grains. When intense starlight hits these grains, it transfers momentum to them, pushing them outward. The dust then drags surrounding gas along with it, creating a steady wind flowing away from the star.

This explanation made sense on paper and worked reasonably well in simplified models. But direct observational proof has always been difficult, mainly because dust grains around stars are extremely small and hard to measure accurately.

A Closer Look at R Doradus

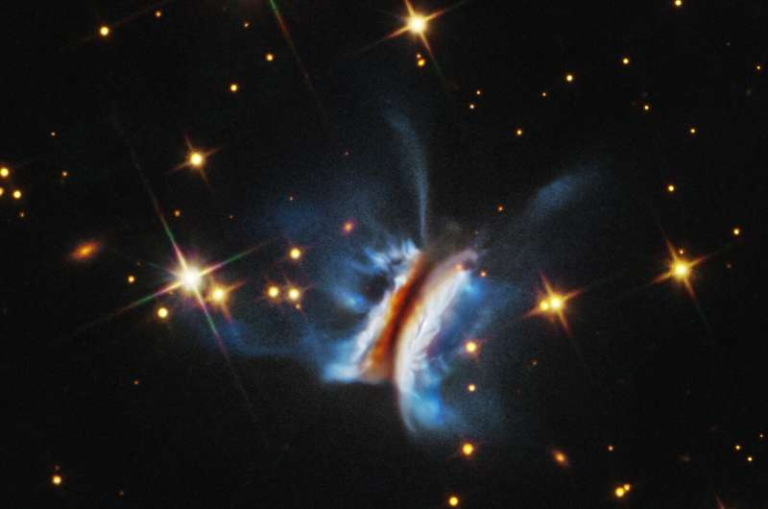

R Doradus is an ideal target for studying stellar winds. It is bright, nearby, and representative of a common type of red giant known as an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star. Located about 180 light-years from Earth, it is close enough for astronomers to study its surface and surrounding dust in remarkable detail.

Using the SPHERE instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, the research team observed light reflected by dust grains surrounding R Doradus. These observations were made in polarized visible light, which is especially useful for determining the size, composition, and distribution of dust particles.

The team focused on a region roughly the size of our solar system, allowing them to study the star’s immediate environment where dust forms and winds are launched.

What the Observations Revealed

The results were surprising. The dust grains around R Doradus turned out to be far smaller than expected, typically only about one ten-thousandth of a millimeter across. The grains were consistent with common types of stardust, such as silicates and alumina, which astronomers have long associated with red giant atmospheres.

However, when the researchers combined their observations with advanced radiative transfer simulations, they found that these tiny grains simply do not feel a strong enough push from starlight. Even when illuminated intensely by the star, the dust cannot gain enough momentum to escape the star’s gravity and drive the observed stellar wind.

In short, dust is present and illuminated—but it is not doing the heavy lifting astronomers once thought it was.

Why This Changes the Big Picture

This finding directly challenges one of the core assumptions in stellar astrophysics. If dust-driven winds are not sufficient—at least in stars like R Doradus—then another mechanism must be helping launch material into space.

This does not mean dust is irrelevant. Dust still plays an important role in cooling stellar atmospheres and shaping circumstellar environments. But it cannot be the sole driver of mass loss in these stars.

For scientists, this kind of result is especially valuable. It forces a re-evaluation of models that have been used for decades and opens the door to new ideas.

Possible Alternatives to Dust-Driven Winds

The researchers point to several other processes that may contribute to launching stellar winds:

- Giant convective bubbles: Observations with the ALMA telescope have previously revealed enormous bubbles rising and falling on the surface of R Doradus. These motions could help lift material away from the star.

- Stellar pulsations: Red giants often expand and contract rhythmically. These pulsations may push gas outward, making it easier for other forces to carry it away.

- Episodic dust formation: Instead of a steady process, dust may form in bursts that temporarily enhance mass loss.

It is likely that multiple mechanisms work together, rather than a single simple process.

How This Affects Our Understanding of Cosmic Chemistry

The way stars lose mass directly influences how galaxies evolve chemically over time. If stellar winds work differently than previously believed, astronomers may need to revise estimates of how quickly and efficiently elements spread through the Milky Way.

This has implications for models of planet formation, star formation, and even the emergence of life-friendly environments. The atoms in your body were once forged in stars, and understanding how those atoms escaped their stellar origins is a fundamental part of cosmic history.

A Reminder That Science Is Always Evolving

One of the most striking aspects of this study is that it highlights how new observational tools can overturn long-standing ideas. Instruments like VLT/SPHERE and ALMA allow astronomers to directly test assumptions that were once based mainly on theory.

Rather than closing a chapter, this research opens a new one. The question of how red giant winds truly work is now more complex—but also far more interesting.