Engineering the First Reusable Launchpads on the Moon and Why Lunar Construction Is Harder Than It Sounds

Building long-lasting structures has always depended on understanding materials. On Earth, civilizations learned through experience which stones, metals, and techniques would endure. But when engineers turn their attention to the Moon, that accumulated knowledge suddenly disappears. The lunar surface is covered in regolith—a dusty, jagged layer of crushed rock formed over billions of years—and despite decades of study, its behavior as a structural material is still full of unknowns.

A recent scientific study published in Acta Astronautica tackles one of the most practical and urgent questions of future lunar exploration: how to engineer the first reusable lunar landing and launch pads using materials found directly on the Moon. The work, led by Shirley Dyke and her research team at Purdue University, focuses on designing landing pads that can function safely even when engineers lack precise data about the Moon’s soil.

Why the Moon Needs Proper Landing Pads

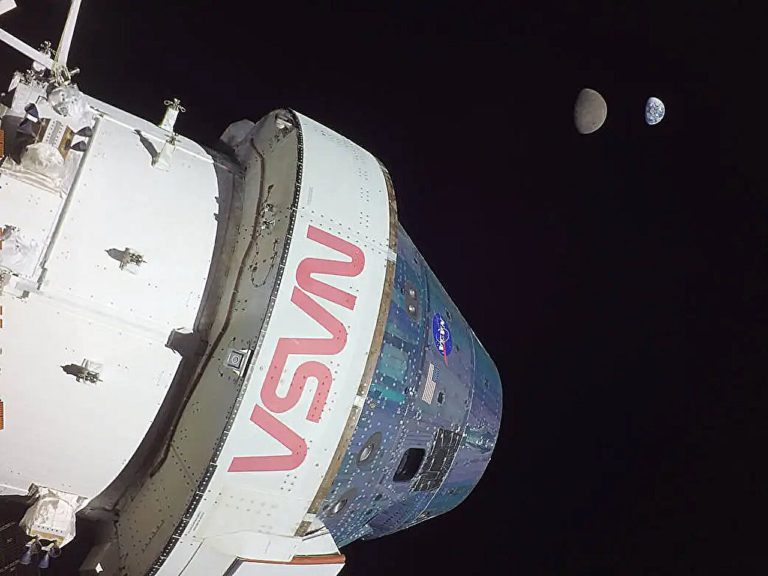

At first glance, it may seem unnecessary to build a dedicated landing pad on the Moon. Modern spacecraft, such as SpaceX’s Starship or future heavy-lift lunar landers, are designed to land autonomously on relatively flat terrain. In theory, they could simply touch down wherever the guidance system finds a suitable spot.

In practice, that approach comes with serious risks. Rocket engines generate enormous force, and when they fire close to the lunar surface, they blast regolith outward at high speeds. Unlike Earth, the Moon has no atmosphere to slow debris down. Dust and rock fragments can travel long distances, threatening nearby habitats, scientific instruments, solar panels, and even the landing spacecraft itself.

Past Apollo missions already demonstrated this danger on a smaller scale. Future missions will involve much heavier vehicles, making the problem far worse. For sustained lunar activity—especially near a permanent base—engineers broadly agree that purpose-built landing pads are essential.

Why Earth-Style Construction Won’t Work on the Moon

On Earth, launch pads are massive concrete and steel structures designed to absorb intense mechanical and thermal loads. Recreating that approach on the Moon would be prohibitively expensive. Transporting enough cement, water, and steel from Earth would require an enormous number of launches.

That is why most lunar construction concepts rely on in-situ resource utilization, or ISRU. In simple terms, this means building things using materials already available on the Moon. Lunar regolith is abundant and doesn’t need to be imported, making it the obvious candidate.

One promising technique for turning loose regolith into a solid structure is sintering. This process uses heat to fuse particles together without fully melting them. Sintered regolith can form hard slabs that resemble stone or low-grade concrete, and multiple space agencies and research groups consider it one of the most viable construction methods for the Moon.

The Big Problem: We Don’t Know the Material Well Enough

Despite its promise, sintered regolith presents a major challenge: its mechanical and thermal properties are poorly understood. Engineers need to know how strong it is under compression, how weak it is under tension, how it expands and contracts with temperature changes, and how it behaves over repeated stress cycles.

Earth-based regolith simulants exist, but they are only approximations. The Moon’s soil has unique characteristics shaped by vacuum conditions, micrometeorite impacts, and extreme temperature swings. According to the researchers, the only way to truly understand how lunar regolith behaves is to test it directly on the Moon.

Rather than waiting for perfect data, the Purdue team proposed a design approach that works with limited information. Their goal was not to finalize a blueprint, but to define engineering boundaries that could guide early construction efforts.

Mechanical and Thermal Stresses on a Lunar Pad

The study identifies two major categories of stress that a lunar landing pad must survive.

The first is mechanical loading. When a spacecraft lands, its weight and thrust forces are transmitted directly into the pad. Sintered regolith is expected to be much stronger in compression than in tension, meaning it handles pushing forces better than pulling forces. This brittleness raises concerns about cracking, especially if loads are uneven.

The second is thermal stress, which may be even more problematic. The Moon experiences a roughly 28-day day-night cycle, with surface temperatures swinging dramatically between extreme heat and extreme cold. These changes cause materials to expand and contract repeatedly.

Rocket exhaust introduces another thermal effect. Analysis suggests that even a powerful rocket plume would only significantly heat the top few centimeters of a sintered regolith slab. That uneven heating creates internal stress, as the hot surface layer tries to expand while the cooler lower layers resist it. Over time, this can cause cracking and surface damage.

How Thick Should a Lunar Landing Pad Be?

Using available estimates from existing literature, the research team modeled a landing pad designed to support a 50-ton lunar lander. Their findings were somewhat counterintuitive.

The optimal pad thickness turned out to be about one-third of a meter, or roughly 14 inches. Making the pad thicker might seem like a safer choice, but the models showed that increased thickness actually raises the risk of thermal fracture. Thicker slabs trap temperature gradients more effectively, making them more prone to warping and cracking.

This insight highlights a key theme of the study: lunar construction is a balance of trade-offs, and more material does not always mean more safety.

Expected Failure Modes Over Time

Even a well-designed lunar pad is not expected to last forever without maintenance. One likely failure mode is spalling, where small chips break off the surface due to repeated thermal expansion and contraction. Over many landings and launches, this gradual erosion could reduce the pad’s load-bearing capacity.

More severe failures could occur if cracks propagate through the slab. These fractures might result from thermal stress, cumulative damage from spalling, or a spacecraft landing slightly off-angle. Because uncertainties exist at nearly every stage, the authors emphasize the importance of continuous monitoring.

Why In-Situ Testing Is Essential

Rather than building a full-scale landing pad immediately, the researchers suggest a phased approach. Early lunar missions could focus on collecting detailed material data, performing controlled tests under real lunar gravity and temperature conditions.

Once a pad is built, it should be instrumented with sensors to track deformation, stress, and temperature changes over time. This data would allow engineers to refine models, predict crack formation, and develop mitigation strategies before serious failures occur.

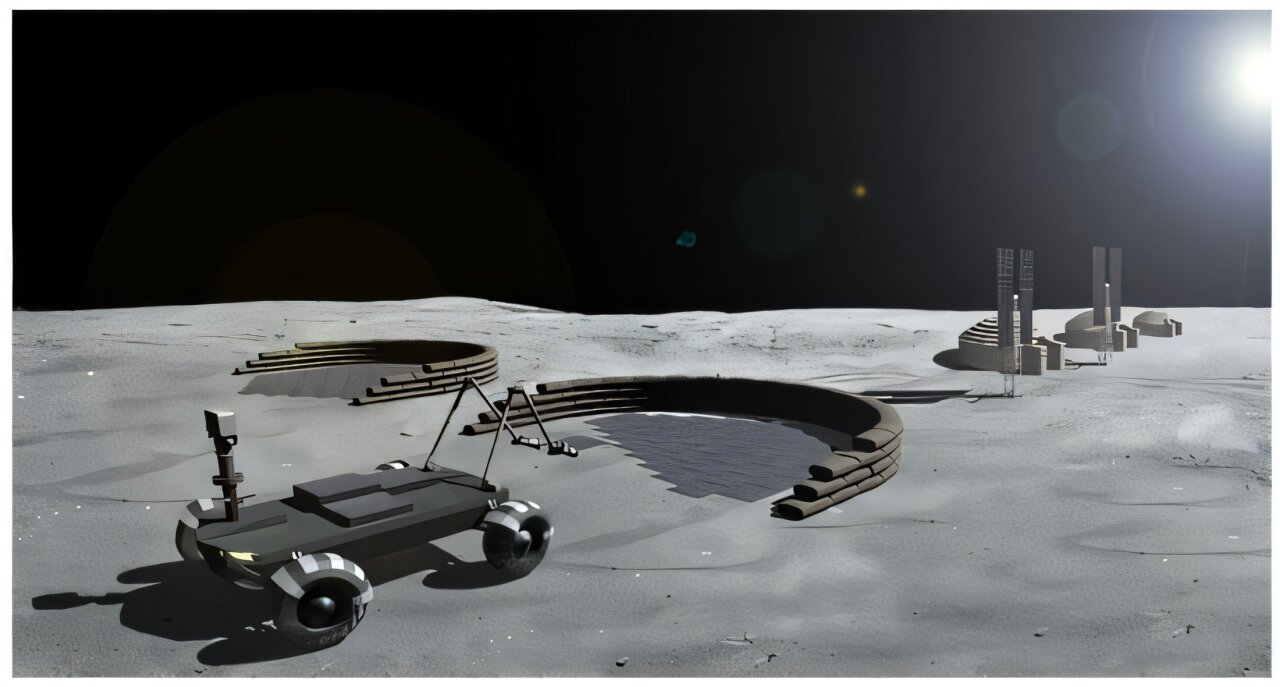

Robots Will Build the Moon’s First Infrastructure

Human construction on the Moon is impractical for large projects. Astronauts operate in bulky spacesuits, tire quickly, and face constant risk. For this reason, the study assumes that robots will handle most lunar construction tasks.

These robots may be teleoperated from Earth or operate autonomously, sintering regolith, assembling slabs, and performing inspections. Robots would also be responsible for maintenance, including repairs and resurfacing as damage accumulates.

The Bigger Picture of Lunar Infrastructure

Reusable landing pads are not just standalone structures. They are foundational elements of a broader lunar infrastructure that could include habitats, research stations, power systems, and fuel depots. Without stable landing zones, sustained lunar activity would be nearly impossible.

While the first reusable lunar pads are still years away, studies like this one provide a realistic engineering framework for moving forward—even in the face of uncertainty. By combining conservative design, iterative testing, and robotic construction, engineers may be able to create safe and durable entry points to the Moon.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2025.11.071