Gemini and Blanco Telescopes Reveal New Clues About the Longest Gamma-Ray Burst Ever Observed

Gamma-ray bursts, commonly known as GRBs, are among the most energetic and violent events in the universe. These immense explosions release more energy in seconds than our Sun will emit over its entire lifetime. Most GRBs appear suddenly and fade just as quickly, lasting anywhere from a fraction of a second to a few minutes. But in early July 2025, astronomers witnessed something entirely different — a gamma-ray burst that refused to end.

On 2 July 2025, space-based instruments detected a gamma-ray event that kept repeating and ultimately lasted more than seven hours, making it the longest gamma-ray burst ever recorded. The event was officially named GRB 250702B, and it immediately sparked intense interest across the global astronomy community.

The first detection came from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which observed repeated bursts of high-energy radiation coming from the same region of the sky. Once Fermi confirmed the unusual persistence of the signal, astronomers rapidly coordinated follow-up observations using telescopes across the world and in space, aiming to understand what could possibly power such a prolonged cosmic explosion.

Pinpointing the Source Beyond Our Galaxy

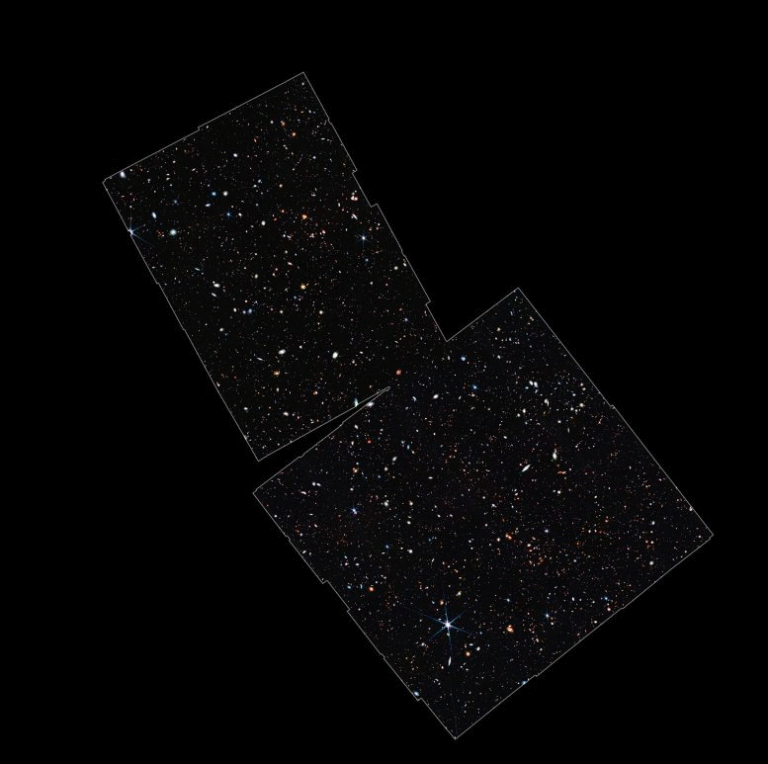

One of the earliest unanswered questions was whether GRB 250702B originated inside the Milky Way or far beyond it. That uncertainty was resolved when infrared observations from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) confirmed that the burst came from a galaxy outside our own.

With its extragalactic origin established, attention quickly turned to capturing the burst’s afterglow — the fading emission that follows the initial gamma-ray flash. Afterglow observations are crucial because they provide information about the environment surrounding the explosion and the physical processes driving it.

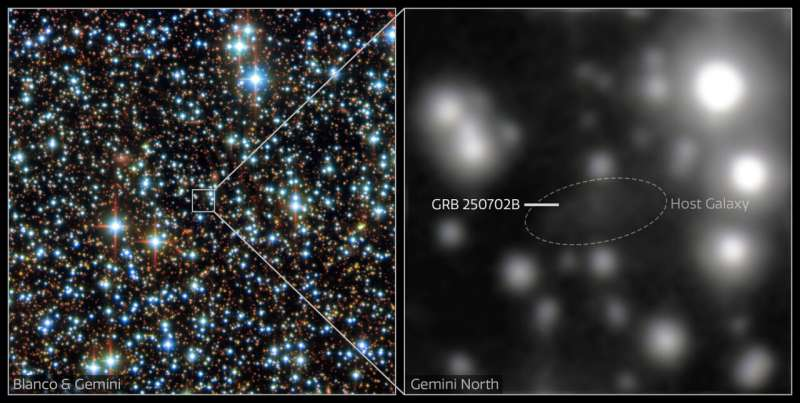

A research team led by Jonathan Carney, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, organized an extensive observing campaign to track the afterglow over time. Their work relied heavily on three major ground-based facilities: the NSF Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope in Chile and the twin 8.1-meter Gemini North and Gemini South telescopes, which together form the International Gemini Observatory.

These telescopes began observing the event about 15 hours after the initial detection and continued monitoring it for roughly 18 days. The findings from this campaign were later published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on 26 November 2025.

Why Dust Played a Major Role in the Observations

One of the most striking discoveries was how difficult GRB 250702B was to observe in visible light. The afterglow was almost completely obscured, not only by dust within the Milky Way but also by an extraordinary amount of dust in the host galaxy itself.

The Gemini North telescope provided the closest-to-visible-light detection of the host galaxy, but even with its powerful optics, astronomers needed nearly two hours of exposure time just to detect the faint signal. The galaxy appeared as a dim oval shape buried beneath thick lanes of dust, explaining why earlier optical surveys had missed it entirely.

To overcome these challenges, the team combined observations from multiple instruments, including the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) and the NEWFIRM infrared imager on the Blanco telescope, along with spectroscopic data from the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrographs (GMOS).

A Massive and Unusual Host Galaxy

Most gamma-ray bursts are found in small, actively star-forming galaxies. GRB 250702B broke that trend. Analysis revealed that its host galaxy is exceptionally massive compared to typical GRB hosts and contains a dense, dust-rich environment.

The data suggest that the burst occurred behind a particularly thick dust lane within the galaxy, which significantly dimmed the visible and ultraviolet light reaching Earth. This dusty environment provides important clues about the conditions surrounding the event and places strong constraints on what kinds of systems could have produced it.

Understanding the Physics Behind the Explosion

By combining their ground-based data with observations from the Keck I Telescope, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the VLT, and various X-ray and radio observatories, the researchers constructed a detailed multi-wavelength picture of GRB 250702B.

Their analysis indicates that the initial gamma-ray emission was produced by a narrow, ultra-fast relativistic jet — a stream of matter traveling at nearly the speed of light — slamming into surrounding material. This interaction generated the intense radiation observed over several hours.

The team also found that the environment around the burst was unusually dense, which likely played a role in sustaining the prolonged emission. When the jet continuously interacts with surrounding material, it can remain active for much longer than in more typical GRB scenarios.

Why GRB 250702B Defies Classification

Since gamma-ray bursts were first identified in 1973, astronomers have cataloged roughly 15,000 GRBs. Only about half a dozen come close to the duration of GRB 250702B, and none exceed it.

Common explanations for long-duration GRBs include the collapse of massive stars or the formation of highly magnetized neutron stars known as magnetars. However, GRB 250702B does not fit cleanly into any established category.

Based on current data, scientists are considering several possible origin scenarios:

- A black hole merging with a helium-rich star that has already lost its outer hydrogen layers

- A micro–tidal disruption event, where a star, planet, or brown dwarf is torn apart by a stellar black hole or neutron star

- A star being destroyed by an intermediate-mass black hole, a type of black hole thought to be common but notoriously difficult to observe

If the last scenario turns out to be correct, GRB 250702B would represent the first direct observation of a relativistic jet produced by an intermediate-mass black hole consuming a star — a milestone in high-energy astrophysics.

Why Ultra-Long Gamma-Ray Bursts Matter

Ultra-long GRBs like GRB 250702B are rare, but they are incredibly valuable to science. They challenge existing models of stellar death and black hole formation and force astronomers to rethink how extreme environments shape cosmic explosions.

These events also act as cosmic probes, illuminating the structure of distant galaxies and revealing how dust, gas, and gravity interact on massive scales. Because GRBs are visible across billions of light-years, they help scientists study the universe as it existed billions of years ago.

What Comes Next

While GRB 250702B has already reshaped ideas about gamma-ray bursts, astronomers emphasize that more observations are needed to pinpoint its true origin. Future discoveries of similar events will help determine whether GRB 250702B is a one-of-a-kind anomaly or the first example of a previously hidden class of cosmic explosions.

For now, it stands as a reminder that even after decades of observing the universe, it still has the ability to surprise us in spectacular ways.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ae1d67