Supermassive Black Holes Show Surprisingly Selective Feeding Habits During Galaxy Mergers

Supermassive black holes have long been thought of as cosmic gluttons, especially during dramatic events like galaxy mergers, when enormous amounts of gas are expected to pour into their surroundings. But new observations suggest that this picture is far more complicated. Using the powerful capabilities of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers have found that even during galaxy mergers—some of the most chaotic and gas-rich events in the universe—supermassive black holes don’t always eat as much as they could.

This research, published in The Astrophysical Journal, reveals that black hole growth during mergers can be surprisingly inefficient and inconsistent. In short, having food nearby does not guarantee that a black hole will actually consume it.

A closer look at merging galaxies and black holes

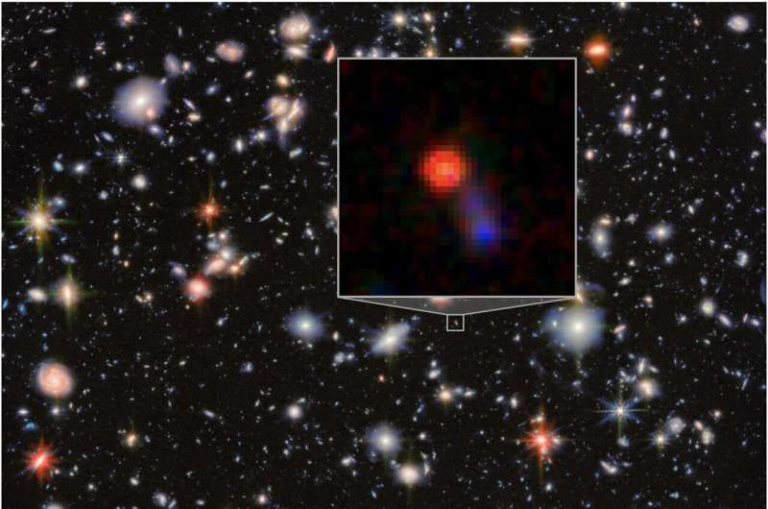

The study focused on seven nearby galaxy mergers, each hosting two supermassive black holes separated by less than 10,000 light-years. These systems are in relatively advanced stages of merging, meaning their galaxies are close enough that gravitational forces are already dramatically reshaping their structures.

When gas-rich galaxies collide, gravity funnels large amounts of cold molecular gas toward their centers. This gas is the primary fuel that allows supermassive black holes to grow and shine as active galactic nuclei (AGN). AGN are among the brightest and most energetic objects in the universe, often outshining their host galaxies.

For years, astronomers have expected that galaxy mergers should commonly produce two simultaneously active black holes, known as dual AGN systems. However, observations have repeatedly shown that dual AGN are relatively rare. Many mergers show only one active black hole, while others show none at all.

This new study helps explain why.

Plenty of gas, but limited feeding

Using ALMA’s ability to map cold molecular gas in exquisite detail, the researchers examined how much gas surrounded each black hole. In many cases—especially around the more massive black holes—they found dense, chaotic reservoirs of gas sitting right near the black hole’s location.

In other words, the fuel was there.

Yet when the team compared the amount of available gas with how brightly the black holes were shining, they found no clear relationship. Black holes surrounded by enormous gas reservoirs were often feeding slowly, while others with less gas could appear more active.

This suggests that black hole feeding during mergers is not steady or efficient, even under ideal conditions. Instead of continuous growth, black holes seem to experience short, irregular feeding episodes, punctuated by long periods of relative inactivity.

Why black holes might refuse to eat

One of the most important insights from the study is that black hole growth appears to be highly variable on short timescales. Even when gas is present, physical conditions may prevent it from actually falling into the black hole.

Several factors likely play a role:

- Turbulence within the gas can disrupt smooth inflow.

- Dust and dense clouds can block or delay accretion.

- Gravitational interactions during mergers can disturb the black hole’s position, making it harder for gas to settle into a stable feeding disk.

In some of the systems studied, the researchers found that one black hole genuinely lacked nearby cold gas, explaining its inactivity. But in other cases, gas was clearly present, and yet the black hole still appeared dormant. The most likely explanation is that astronomers were observing these systems between feeding episodes.

Single AGN versus dual AGN systems

The team compared mergers hosting dual AGN with those showing only a single active black hole. This comparison revealed that the difference between these systems is not always the amount of available gas.

In some mergers, both black holes had access to gas, but only one was actively feeding at the time of observation. This reinforces the idea that timing is critical. Because AGN activity can flicker on and off over relatively short periods, it is statistically difficult to catch both black holes actively feeding at the same moment.

This variability helps explain why astronomers so rarely observe dual AGN, even though galaxy mergers themselves are common.

Black holes knocked off-center

Another intriguing result from the ALMA observations is that many active black holes were found slightly offset from the centers of their surrounding gas disks. This displacement is likely caused by violent gravitational interactions during the merger process.

When black holes are not perfectly centered, gas has a harder time settling into stable orbits that allow efficient accretion. This spatial mismatch may further limit how much material the black hole can consume, even when gas is abundant.

Why ALMA made this study possible

These discoveries were only possible because of ALMA’s unique capabilities. ALMA can observe cold molecular gas at extremely high resolution, allowing astronomers to see exactly where the fuel for black hole growth is located.

Earlier studies often relied on indirect indicators of gas or lower-resolution observations, making it difficult to link gas availability with black hole activity on small scales. ALMA’s observations provide a direct view of the complex environments surrounding supermassive black holes during mergers.

What this means for galaxy evolution

Supermassive black holes and their host galaxies are known to evolve together. There is a well-established relationship between the mass of a galaxy’s central black hole and properties like the galaxy’s bulge size and stellar mass.

Galaxy mergers have long been thought to play a key role in establishing this connection. However, these new findings suggest that black hole growth during mergers is far from straightforward. Simply delivering gas to the center of a galaxy is not enough. The gas must also be able to lose energy, overcome turbulence, and fall inward at the right time.

This means that black hole growth may be less efficient and more chaotic than many models assume, potentially requiring revisions to how astronomers simulate galaxy evolution across cosmic time.

Extra context: how supermassive black holes usually feed

Outside of mergers, supermassive black holes typically grow by pulling in gas through a rotating accretion disk. In calmer galaxies, structures like bars, spiral arms, or interactions with smaller companions can slowly funnel gas inward.

Even in these quieter environments, black hole feeding is often inefficient. Much of the gas may form stars or be blown away by radiation and jets before ever reaching the event horizon. The new merger-focused study shows that even extreme events don’t guarantee efficient feeding, reinforcing the idea that black hole growth is fundamentally intermittent.

A more nuanced picture of cosmic giants

Overall, this research paints a more realistic and nuanced picture of supermassive black holes. They are not mindless vacuum cleaners that consume everything in reach. Instead, their growth depends on a delicate balance of gas dynamics, timing, turbulence, and gravitational chaos.

Galaxy mergers may deliver the ingredients for rapid black hole growth, but whether that growth actually happens is a matter of circumstance. In the universe, even the biggest eaters can be surprisingly picky.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ae1600