Rethinking How We End a Satellite’s Mission and What It Means for Earth’s Atmosphere

At the end of their operational lives, most satellites don’t retire quietly. Instead, they plunge back toward Earth, meeting a fiery end as they reenter the atmosphere. For decades, this approach has been considered a responsible way to deal with defunct spacecraft. But new research suggests that the way we dispose of satellites may come with environmental consequences that have not received enough attention—especially as thousands of new satellites are launched every year.

A recent scientific study is prompting engineers, regulators, and satellite designers to rethink long-standing assumptions about satellite end-of-life strategies. The issue isn’t just about space debris or ground safety anymore. It’s also about what happens to Earth’s atmosphere when satellites burn up overhead.

Why Most Satellites Burn Up on Reentry

The majority of satellites, particularly smaller ones used in low Earth orbit (LEO), are intentionally designed to disintegrate when they fall back to Earth. This design philosophy is known as Design for Demise (D4D). The idea is simple: if a satellite completely burns up in the atmosphere, it can’t hurt anyone on the ground.

This approach is especially common for satellites launched as part of massive “mega-constellations,” such as broadband internet networks. These constellations can include tens of thousands of spacecraft, many of which are designed to last only a few years before being replaced.

From a safety perspective, D4D has long been seen as a success. But according to a paper published in Acta Astronautica by Antoinette Ott and Christophe Bonnal of MaiaSpace, the environmental side effects of this strategy deserve closer scrutiny.

The Unexpected Atmospheric Impact of Satellite Reentry

When a satellite reenters Earth’s atmosphere at high speed, it releases a tremendous amount of energy. This energy doesn’t just make the satellite burn—it also alters the chemistry of the surrounding air.

Two byproducts are particularly concerning: nitrogen oxides (NOx) and alumina.

Nitrogen Oxides and the “Cooking the Air” Effect

Nitrogen oxides are well known for their role in ozone depletion and air pollution. On Earth, NOx is produced by engines and industrial processes, and entire emission control systems exist to limit its release.

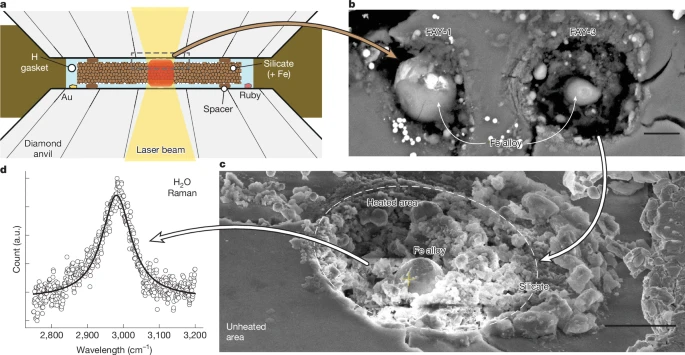

Satellite reentry produces NOx in a very different way. As a spacecraft hurtles through the atmosphere, powerful shockwaves form around it. These shockwaves heat the surrounding air to extreme temperatures, forcing nitrogen and oxygen molecules to combine. This process is known as the Zeldovich mechanism.

Researchers estimate that up to 40% of the energy from a reentering spacecraft’s mass may be converted into NOx. Unlike ground-based emissions, this NOx is created high in the atmosphere, where it can directly interact with ozone-rich layers.

In simple terms, satellites are effectively “cooking the air” as they fall back to Earth.

Alumina and Its Role in Ozone Chemistry

The second major concern comes from the satellite itself. Many spacecraft are built using aluminum because of its low melting point and favorable structural properties. Aluminum makes it easier for satellites to burn up completely during reentry, aligning well with D4D principles.

However, when aluminum burns, it forms alumina, or aluminum oxide. These tiny particles don’t disappear immediately. Instead, they accumulate in the stratosphere at around 20 kilometers altitude.

Alumina has complex effects on the atmosphere. It tends to cool the lower atmosphere while warming the upper layers, potentially disrupting weather patterns. More importantly, alumina particles can act as surfaces that activate chlorine, one of the most destructive chemicals when it comes to ozone depletion.

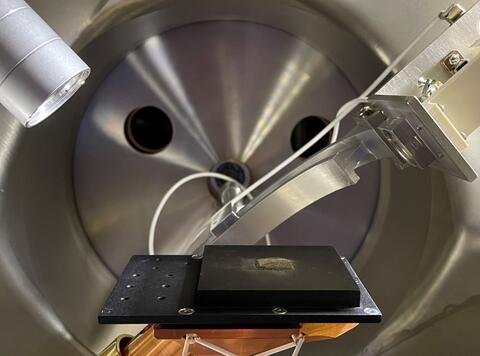

Some alumina in the stratosphere is natural, mostly originating from meteors that burn up as they enter Earth’s atmosphere. But models suggest that human-made satellites could cause a 650% increase in alumina levels in the coming decades. Observations already hint that this process is underway. Data from NOAA’s SABRE mission indicates that around 10% of sulfuric acid particles in the stratosphere already contain alumina.

Mega-Constellations Are Changing the Scale of the Problem

The environmental impact of satellite reentry becomes far more serious when viewed through the lens of scale. A handful of satellites burning up each year is one thing. Tens of thousands is another.

Companies like SpaceX plan to operate fleets with upwards of 40,000 satellites, continuously replenishing them as older units fail or are upgraded. Each satellite may meet safety standards individually, but collectively they represent a constant stream of material entering the atmosphere.

This sheer volume raises uncomfortable questions about whether current models for atmospheric impact are sufficient—or even accurate.

The Alternative: Keeping Satellites Intact

In response to these concerns, researchers are revisiting an alternative approach known as Design for Non-Demise (D4ND). Instead of allowing satellites to break apart and burn up, D4ND aims to keep spacecraft largely intact during reentry.

The potential benefit is clear: fewer chemical byproducts released into the upper atmosphere. But this approach introduces its own risks.

If a satellite survives reentry, it must land somewhere. That creates the possibility—however small—of debris striking people or property on the ground. International standards like ISO 27875 limit the acceptable risk of casualty from reentering objects to 1 in 10,000. While that might sound reassuring, the math becomes less comforting when thousands of satellites are involved.

Evidence already suggests that some satellites don’t fully disintegrate as planned. SpaceX and the US Federal Aviation Administration have openly discussed cases where parts of Starlink satellites appear to have reached the ground intact, raising questions about how effective current D4D designs really are.

Controlled Reentry and Its Trade-Offs

Another option is controlled reentry, where satellites are deliberately guided to crash into remote areas, typically over the Pacific Ocean. This approach minimizes the risk to people and infrastructure but comes at a cost.

Satellites must be heavier and stronger to survive controlled descent, and they need extra fuel to maneuver precisely to safe reentry zones. Added mass means higher launch costs, which is never popular in a commercial industry.

That said, launch prices are falling, and some experts believe the trade-off may be worth it if it reduces long-term environmental harm.

No Easy Answers, but Important Questions

According to Ott, there is no single “right” solution to the problem of satellite disposal. Each strategy—D4D, D4ND, or controlled reentry—comes with its own mix of environmental, economic, and safety risks.

What the research makes clear is that these trade-offs should be considered from the very beginning of satellite design, not as an afterthought. New modeling tools are being developed to better quantify both atmospheric impact and ground risk, and there may be hybrid approaches, such as Design for Containment, that limit the downsides of existing strategies.

Why This Matters for the Future of Space

Low Earth orbit is rapidly becoming critical infrastructure. Satellites support communication, navigation, weather forecasting, Earth observation, and scientific research. As reliance on space-based systems grows, so does the responsibility to manage them sustainably.

How we end a satellite’s mission may seem like a minor detail compared to launch or operation, but this research shows it can have planet-wide consequences. Protecting people on the ground is essential—but so is protecting the atmosphere that makes life on Earth possible.

Balancing these priorities will be one of the defining challenges of the next era of space activity.

Research paper:

Atmospheric re-entry of orbital objects—can Design For Non-Demise be the optimal solution?

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2025.08.002