Turning Structural Failure Into Propulsion With a New Way to Steer Solar Sails

Solar sails have long fascinated scientists because they offer a way to travel through space without using any propellant at all. Instead of burning fuel, these sails rely on sunlight itself. Photons from the Sun strike a large, reflective surface and transfer momentum, slowly but continuously pushing a spacecraft forward. Over long periods, this gentle pressure can move a spacecraft across vast distances.

Despite this elegant idea, solar sails have always faced one stubborn problem: how do you steer them?

A new research paper by Gulzhan Aldan and Igor Bargatin from the University of Pennsylvania, recently published on the arXiv preprint server, proposes an inventive solution. Their approach turns what engineers normally try to avoid — structural buckling and material failure — into a useful tool for propulsion and control. The key inspiration comes from kirigami, the Japanese art of cutting paper.

Why Steering a Solar Sail Is So Difficult

With traditional spacecraft, changing direction is relatively straightforward. Thrusters fire, momentum changes, and the craft turns. Solar sails, however, have no engines and no exhaust. They are pushed only by light, and that light is incredibly weak.

On Earth, sailing ships can adjust the angle of their sails and use a rudder to steer. Solar sails can adjust their orientation to sunlight, but they don’t have anything equivalent to a rudder. Once a sail is deployed in space, any steering system must be lightweight, reliable, and extremely energy-efficient.

Over the years, engineers have tried several solutions:

- Reaction wheels, commonly used on satellites, can rotate a spacecraft internally. These systems are heavy and can saturate, requiring additional systems to reset them.

- Tip vanes, small adjustable mirrors placed at the corners of a sail, can redirect sunlight to create torque. While clever, they introduce mechanical complexity and can fail.

- Reflectivity Control Devices (RCDs), like those flown on Japan’s IKAROS mission in 2010, use liquid crystal panels that switch between reflective and absorptive states. These work well but require continuous electrical power to maintain their configuration.

Each method works, but all come with trade-offs in mass, power consumption, or reliability.

Kirigami as a New Control Strategy

The new idea proposed by Aldan and Bargatin takes a very different approach. Instead of adding more hardware, they modify the sail material itself.

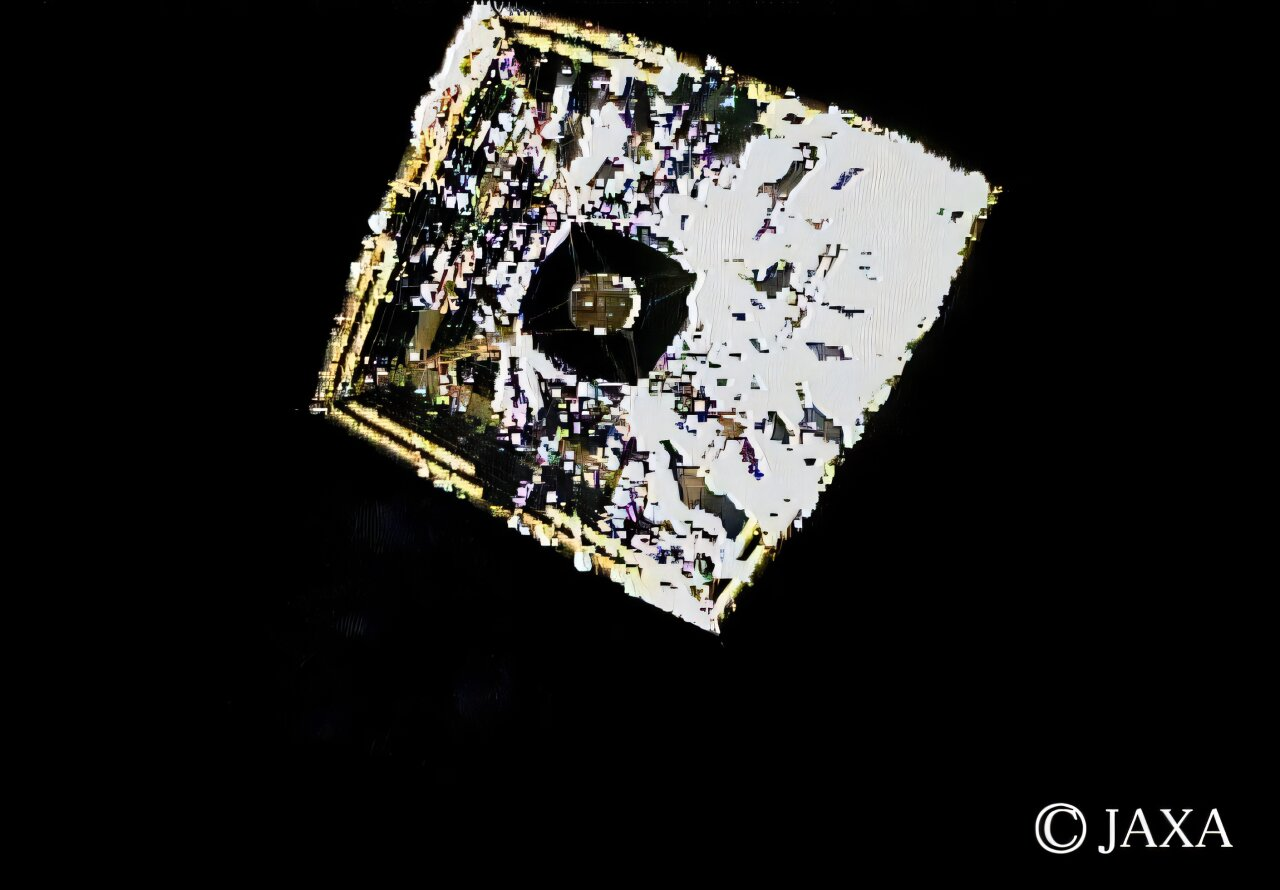

Kirigami, unlike origami, involves cutting material rather than folding it. The researchers apply this idea to solar sail films, which are typically made from aluminized polyimide, a lightweight and highly reflective material already used in space missions.

In their design, the sail surface is divided into a grid of small panels, or unit cells. Each unit cell contains carefully designed cuts running in axial and diagonal directions. When the sail is stretched, these cuts allow the material to buckle out of the plane, forming small three-dimensional shapes.

This buckling is not random. It is tunable and predictable, meaning engineers can control how much each section tilts relative to incoming sunlight.

How Buckling Becomes Propulsion

Once the sail surface buckles, something interesting happens. Each tilted segment acts like a tiny mirror, reflecting sunlight at a slightly different angle. According to the conservation of momentum, when light changes direction after bouncing off a surface, it exerts a force on that surface.

Individually, these forces are extremely small. But across thousands of buckled segments, they add up. By controlling which regions buckle and by how much, the sail can generate in-plane forces that gently rotate or steer the spacecraft.

This turns a structural effect normally associated with failure into a functional control mechanism.

Power Use and Mechanical Simplicity

One of the most appealing aspects of the kirigami sail is its low power requirement. Creating the buckling requires small actuators, such as servo motors, to apply tension to the sail. These motors only draw power while adjusting the sail.

This is a major advantage over Reflectivity Control Devices, which must continuously consume power to maintain a reflective or absorptive state. Once the kirigami sail is set into a particular configuration, it can remain that way without ongoing energy use.

Simulation Results and Measured Forces

To test their idea, the researchers first turned to simulation. Using COMSOL, a widely used physics simulation software, they conducted ray-tracing experiments to model how light interacts with the buckled sail surface.

The simulations measured the forces produced under various buckling angles and solar illumination conditions. The results showed that the system produces about 1 nanonewton of force per watt of sunlight. While this is a tiny force, solar sails operate over months or years, making even such small forces useful for attitude control.

Laboratory Experiments With Lasers

The team also validated their concept experimentally. They fabricated kirigami-cut films and placed them inside a test chamber. A laser was directed at the film while the material was stretched.

As the strain increased, the buckled sections changed shape, and the reflected laser spot moved across the chamber wall. The observed reflection angles closely matched the predictions from the simulations, confirming that the buckling behavior was both controllable and repeatable.

How This Fits Into the History of Solar Sailing

Solar sails are not just theoretical. Japan’s IKAROS mission, launched in 2010, successfully demonstrated interplanetary solar sailing and used RCDs for steering. More recently, The Planetary Society’s LightSail missions showed that small spacecraft could raise their orbits using sunlight alone.

The kirigami approach adds a new option to the growing toolkit of solar sail control technologies. It does not replace existing methods outright but offers a lighter and potentially more energy-efficient alternative.

Challenges and Future Testing

Despite its promise, the kirigami sail concept is still in the early stages. The experiments were conducted in laboratory conditions, not in space. Future work will need to address how these materials behave under vacuum, extreme temperatures, radiation, and micrometeoroid impacts.

There is also the question of scalability. While the technique appears well-suited for small solar sails and CubeSat-scale missions, engineers will need to explore how it performs on much larger sails.

Why This Research Matters

This work highlights a broader trend in space engineering: using material science and structural mechanics in creative ways. Instead of fighting buckling and deformation, the researchers embrace them as tools.

If proven reliable in space, kirigami-based control could reduce the mass, complexity, and energy demands of future solar sail missions. That could make long-duration, deep-space exploration more affordable and more feasible.

In the long run, such innovations may play a key role in missions to asteroids, the outer planets, and even interstellar space, where carrying large amounts of propellant is simply not practical.

Research paper:

Low-Power Solar Sail Control using In-Plane Forces from Tunable Buckling of Kirigami Films

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.13596