Antibodies’ Decoy Tactics for Outmaneuvering Pathogens Could Inspire Next-Generation Treatments

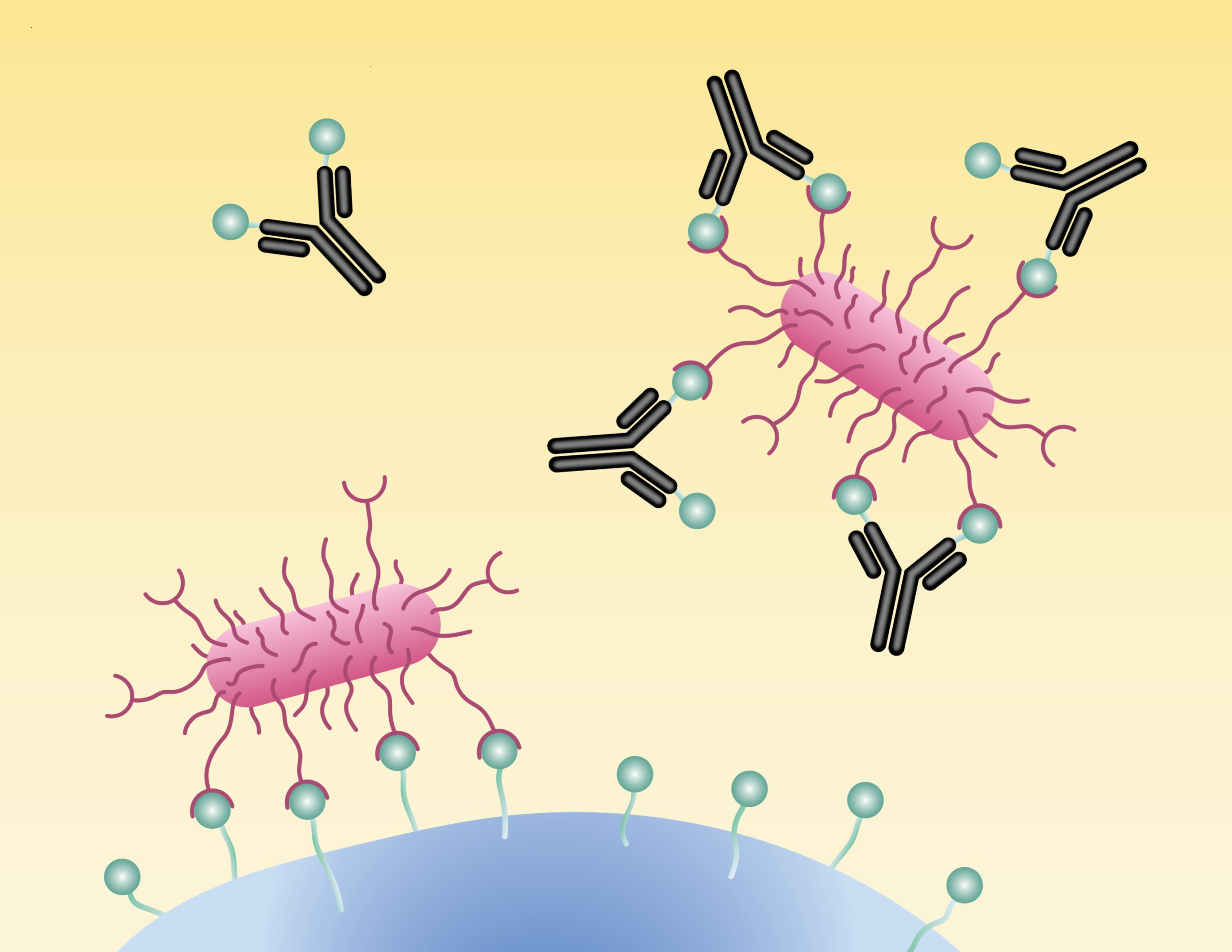

Pathogens are remarkably good at one simple but dangerous trick: sticking to our cells. For many bacteria and viruses, attachment is the very first step toward infection. If a microbe cannot latch on, it often cannot invade, multiply, or cause disease. A new study from researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine takes a deep dive into how certain antibodies disrupt this process—and the findings could reshape how we think about preventing and treating infections.

The research focuses on Escherichia coli (E. coli) strains that cause urinary tract infections (UTIs), one of the most common bacterial infections worldwide. Once these bacteria gain a strong grip on bladder cells, they can be extremely difficult to remove. What the scientists discovered is that some antibodies don’t just block bacteria in the usual ways. Instead, they use clever molecular deception, acting as decoys that fool pathogens into binding to them rather than to human cells.

Why Bacterial Attachment Matters So Much

For many microbes, infection begins with adhesion. Bacteria use specialized surface proteins—often called adhesins—to recognize and bind to receptors on human cells. In the case of UTI-causing E. coli, these adhesins allow the bacteria to cling tightly to bladder tissue, resisting the natural flushing action of urine.

Once attachment occurs, bacteria can form communities, evade immune defenses, and trigger inflammation. That’s why blocking adhesion has long been considered a promising strategy for infection control. Unlike antibiotics, which aim to kill bacteria or stop them from growing, anti-adhesion strategies focus on preventing infection before it even starts.

Multiple Ways Antibodies Interfere With Bacterial Gripping

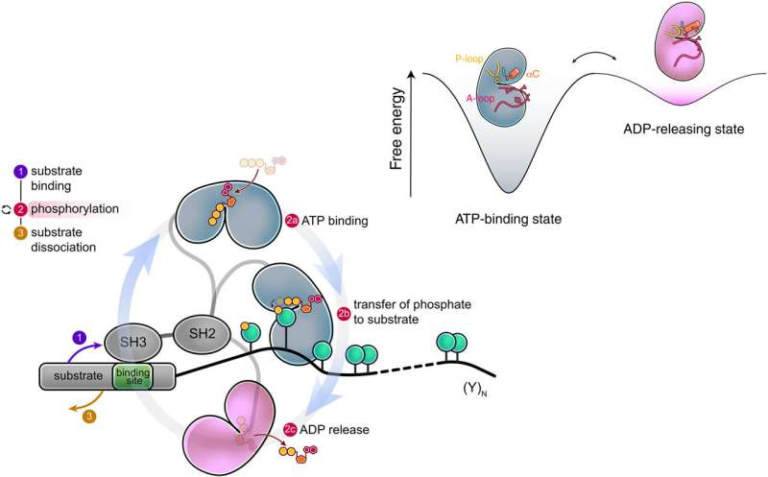

The UW research team found that antibodies can interfere with bacterial adhesion through several distinct mechanisms, not just one. These mechanisms work at the molecular level, targeting the very proteins bacteria rely on to grab onto cells.

Some antibodies act as molecular wedges, physically inserting themselves into key regions of the bacterial adhesion proteins and blocking their ability to function. Others create conformational traps, locking the bacterial proteins into shapes that can no longer bind effectively to host receptors. Another strategy involves pocket locking, where antibodies bind at one site but indirectly alter the structure of the adhesion protein elsewhere, preventing it from doing its job.

What makes these findings especially interesting is that these approaches don’t rely on destroying the bacteria outright. Instead, they neutralize the bacteria’s ability to attach, making them easier for the immune system to clear.

The Standout Discovery: Antibodies That Act as Decoys

Among all the mechanisms uncovered, one stood out as particularly surprising. The researchers identified a newly recognized class of antibodies that carry a molecular feature known as a glycan—a complex carbohydrate structure commonly found on cell surfaces.

In this case, the glycan attached to the antibody closely resembles the glycan-like receptors found on bladder cells. The E. coli bacteria mistake this antibody-bound glycan for their intended target. As a result, the bacteria bind to the antibody instead of to human tissue.

This is ligand mimicry in action. The antibody essentially disguises itself as a host cell receptor, tricking the bacteria into making a fatal error. Once bound to the antibody, the bacteria are blocked from attaching to real cells and are also flagged for destruction by the immune system.

Until now, antibodies carrying receptor-mimicking glycans had not been clearly documented as antimicrobial tools, despite the fact that many antibodies are known to carry glycans of various types. This discovery opens the door to a whole new way of thinking about antibody function.

How the Researchers Studied These Interactions

To uncover these mechanisms, the scientists used a combination of advanced techniques. These included cryo-electron microscopy, which allowed them to visualize the structures of antibodies and bacterial proteins at near-atomic resolution. They also employed mass spectrometry to analyze molecular compositions, along with adhesion assays to test how well bacteria could attach under different conditions.

In addition, the team ran molecular dynamics simulations on the Expanse supercomputer in San Diego. These simulations helped them understand how antibody binding affects the movement and shape of bacterial adhesion proteins over time.

Together, these methods provided a detailed picture of how antibodies disrupt bacterial attachment in real, physical terms—not just in theory.

Implications Beyond Urinary Tract Infections

While this study focused on UTI-causing E. coli, the researchers believe the findings are likely broadly applicable. Many bacterial and viral pathogens rely on adhesion proteins to infect host cells. The same antibody strategies described here could potentially work against other bacteria, viruses, pathogenic fungi, and even some parasites.

There are also implications beyond infectious disease. Certain microbial glycan-binding proteins resemble molecules that can interact with B cells, including abnormal B cells involved in some lymphomas. This raises the possibility that microbial antigens could influence tumor growth or persistence in specific cancers.

Additionally, because normal B cells are central to immune function, repeated exposure to microbial adhesion proteins might contribute to autoimmune disorders by overstimulating B cell receptors. These connections are still being explored, but the findings provide valuable clues.

What This Means for Vaccines and Therapies

The discovery of anti-adhesion antibodies with decoy capabilities offers a promising starting point for new immune-based therapies. Instead of focusing solely on killing pathogens, future treatments might aim to block attachment, making infections less likely to take hold in the first place.

This approach could be especially valuable at a time when antibiotic resistance is a growing global concern. Therapies that disarm bacteria without killing them may place less selective pressure on microbes to evolve resistance.

However, the researchers also caution that anti-adhesion antibodies may not always be beneficial. In some cases, interfering with microbial interactions could have unintended side effects. These risks will need careful consideration when designing vaccines or antibody-based treatments that rely on these mechanisms.

A Broader Look at Glycans and Host–Pathogen Interactions

Glycans play a central role in how microbes and hosts interact. Many pathogens recognize specific glycan patterns on human cells, using them as docking points. At the same time, glycans are involved in immune recognition, cell signaling, and inflammation.

By showing that antibodies can use glycan mimicry as a defensive strategy, this study highlights just how sophisticated immune responses can be. It also reinforces the idea that understanding glycobiology—the study of sugars and carbohydrates in biological systems—is crucial for developing next-generation medical interventions.

Looking Ahead

This research adds an important new chapter to our understanding of antibodies. Far from being simple blockers or neutralizers, some antibodies act as strategic decoys, exploiting the pathogen’s own attachment machinery against it.

As scientists continue to explore these mechanisms, the hope is that they will lead to innovative treatments and preventive strategies that stop infections before they start. In a world facing rising antibiotic resistance and persistent infectious threats, that kind of insight couldn’t be more timely.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65666-3