How Strange Ancient Sea Creatures Became Some of the Best-Preserved Fossils on Earth

Soft-bodied creatures and fossils usually don’t go together. Animals without shells, bones, or hard skeletons typically decay long before they ever have a chance to leave a mark in the geological record. That’s why fossils of jellyfish-like organisms or soft, flexible life forms are extremely rare. Yet around 570 million years ago, during a period known as the Ediacaran, something extraordinary happened. Entire communities of soft-bodied organisms were preserved in astonishing detail—imprinted into sandstone, of all things.

These fossils, collectively known as the Ediacara Biota, are now found in rock formations across the globe. Their preservation has puzzled scientists for decades, especially because sandstone is usually one of the worst materials for fossil formation. New research, however, is finally providing a clear explanation for how this unlikely fossil record came to be.

Why These Fossils Are So Unusual

Under normal circumstances, fossilization favors hard materials. Shells, teeth, and bones survive burial, pressure, and time far better than soft tissue. Sandstone adds another layer of difficulty. Its large grain size, high porosity, and tendency to form in energetic environments shaped by waves and storms usually destroy delicate remains.

Despite all of this, Ediacaran fossils show remarkably sharp outlines, fine surface textures, and clear impressions of soft bodies. Many of these organisms appear flattened against ancient seafloors, almost as if they were pressed into wet cement. This level of preservation in sandstone is not just rare—it’s extraordinary.

Meet the Ediacara Biota

The Ediacara Biota represent some of the earliest large and complex organisms known to science. Their shapes are unlike most animals alive today. Some display three-fold symmetry, others have spiraling arms, while many show repeating fractal patterns. Because of their unusual forms, scientists still debate how many of them relate to modern animals, if at all.

These organisms lived during a crucial evolutionary window. They appeared only tens of millions of years before the Cambrian Explosion, a period beginning around 540 million years ago when animal diversity and complexity increased dramatically. Rather than a sudden burst of life from nothing, evidence increasingly suggests a “long fuse”, with the Ediacara Biota playing a key role in that gradual buildup.

A New Explanation Rooted in Chemistry, Not Biology

For years, one hypothesis suggested that Ediacaran organisms might have had unusually tough or resilient tissues that helped them fossilize. The latest research challenges that idea directly.

A study led by paleontologist Lidya Tarhan of Yale University, published in the journal Geology, shows that the secret lies not in the organisms themselves, but in the chemical conditions of the seafloor where they were buried.

The research focuses on a process known as Ediacara-style exceptional fossilization, where soft-bodied organisms are preserved as impressions in sandstone. Tarhan and her colleagues investigated fossil sites in Newfoundland and northwest Canada, areas famous for well-preserved Ediacaran fossils found in both sandy and muddy sediments.

How Clay Minerals Made the Difference

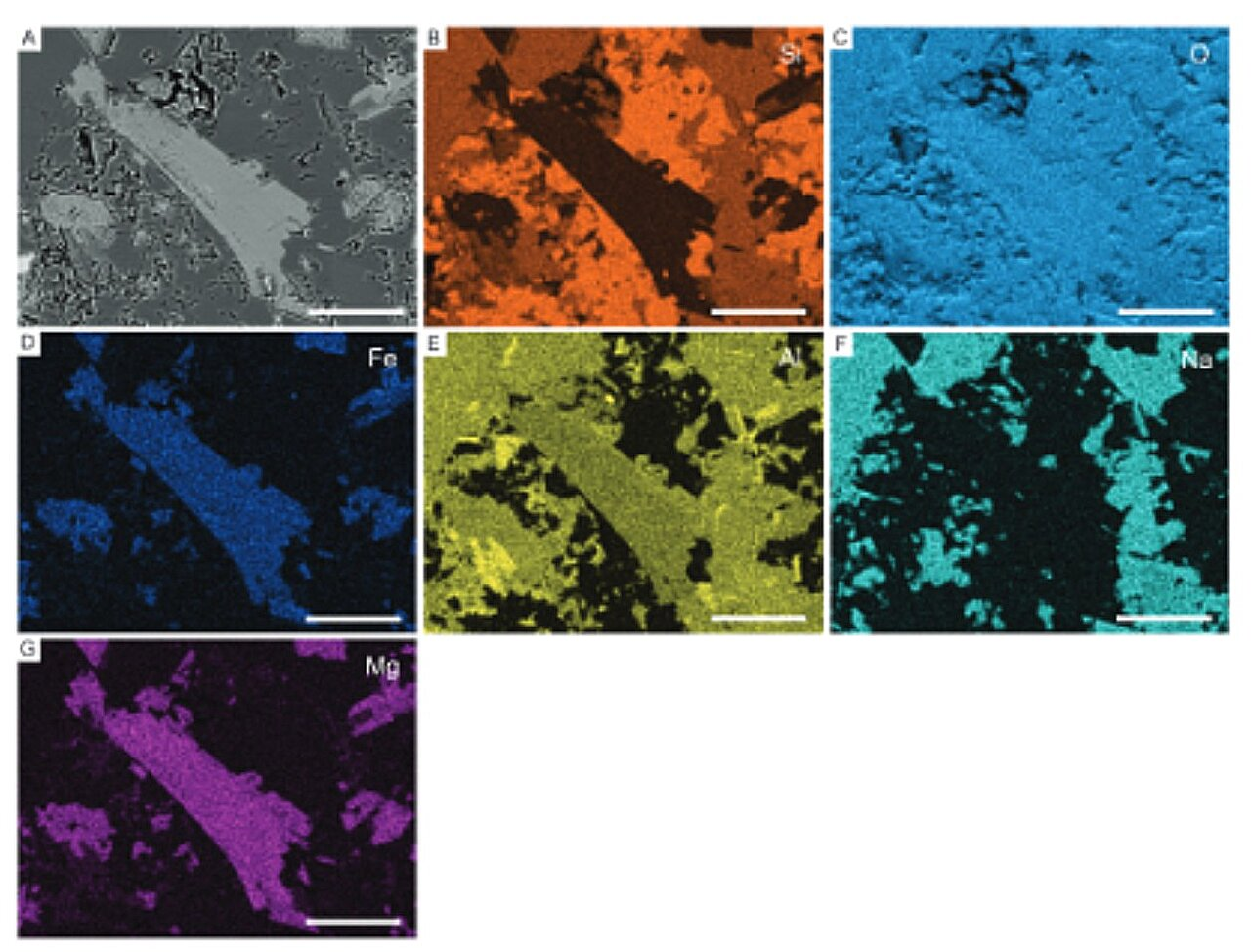

The key players in this fossilization process turned out to be clay minerals, studied using an innovative method involving lithium isotopes. Lithium behaves differently depending on how minerals form, making it an effective tracer for distinguishing between different geological processes.

The researchers discovered two types of clays involved:

- Detrital clays, which were eroded from continental rocks and transported into the ocean.

- Authigenic clays, which formed directly within the seafloor sediments after burial.

The detrital clay particles were already present in the sediment that buried the organisms. These particles acted as nucleation sites, allowing new clay minerals to grow in place. Thanks to the unusual chemistry of Ediacaran seawater, which was rich in silica and iron, authigenic clays precipitated rapidly within the upper layers of the seafloor.

These newly formed clays effectively cemented the sand grains together, stabilizing the sediment before the soft-bodied organisms could fully decay. As a result, the outlines and surface details of the organisms were locked in place, creating high-resolution impressions that survived for hundreds of millions of years.

Why Sandstone Suddenly Worked

This discovery explains why sandstone, normally a poor medium for fossil preservation, became an unlikely archive of ancient life during the Ediacaran. The authigenic clay cement reduced porosity and limited sediment movement, protecting fragile biological shapes from collapse or erosion.

Importantly, this mechanism does not rely on rapid burial alone. Instead, it highlights the importance of seafloor geochemistry, showing that the right chemical conditions can dramatically expand what kinds of fossils are possible.

What This Means for Evolutionary History

Understanding how the Ediacara Biota were preserved helps scientists answer a much bigger question: how accurately does the fossil record reflect early complex life?

If preservation depended heavily on environmental chemistry, then similar organisms may have existed elsewhere but failed to fossilize. This realization forces researchers to rethink gaps in the fossil record and reconsider long-standing ideas about when and how complex life first appeared.

The study also has implications beyond the Ediacaran. Tarhan plans to apply the same lithium isotope techniques to fossils from other time periods to see whether similar clay-driven preservation occurred elsewhere in Earth’s history.

Additional Context: Life Before the Cambrian Explosion

Before the Ediacaran, Earth was dominated by microbial life for billions of years. The sudden appearance of large, complex organisms represents one of the most dramatic transitions in the planet’s biological history.

During the Ediacaran, oceans lacked many of the predators and burrowing animals common today. This relatively stable seafloor environment may have further aided preservation by minimizing physical disturbance. Combined with unique seawater chemistry, these conditions created a rare taphonomic window—a brief period when soft-bodied organisms had an unusually high chance of being fossilized.

Why This Research Matters Going Forward

By pinpointing the exact mechanisms behind Ediacaran fossilization, scientists can better evaluate competing hypotheses about why these organisms appeared when they did—and why they later disappeared at the close of the Ediacaran period.

More broadly, this research reinforces an important idea in paleontology: what we see in the fossil record is shaped as much by geology and chemistry as by biology itself. Exceptional fossils don’t just tell us about ancient organisms—they tell us about ancient environments.

Research Paper:

Authigenic clays shaped Ediacara-style exceptional fossilization

Geology (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1130/G53967.1